Hold Me As I

When was the last time you blindly bought an album.

And I suppose I am showing my age, here. Dating myself. I almost always am. I think it happens when you find yourself lamenting about how quickly things move—the zeitgeist, or whatever, and how difficult it can feel, at times, to keep up with the pace, and take everything in.

It happens when you are perhaps too nostalgic for your own good. You remember dates. Times. Moments. The kind of minutiae others would not give a second thought to.

I am remiss to say it is impossible to blindly purchase an album—though it is an action that, more and more, is extremely difficult to do. It is a challenge, in many cases, to know little if anything at all about an album—some kind of compelling backstory it might have, let alone what the music included on it might sound like. It’s hard not to have heard at least one song, in order to better inform your decision.

If this is an album you wish to listen to, or purchase.

And there was a point when there was less—just less, overall, readily available to us at any moment. There was a time when you could not pull up an artist, or an album, on your mobile device, and listen to it through the streaming platform of your choice. There was a time before the 30-second previews offered through iTunes, or even on Amazon. There was a time when you had to catch a song on the radio, or see a video for it, to know about it, and the artist responsible. There was a point when the idea of “word of mouth” was much, much slower than it is today, in terms of how information travels, and how quickly it gets from one person to another.

I don’t remember the name of the magazine, unfortunately. If I am recalling correctly, though, it would have been a music magazine dedicated, primarily, to electronic music, that I bought at the bookstore in the small, rural, Illinois town I grew up in, near the tail end of the year 2000, or at the beginning of the new year. The magazine, as many music magazines of the time did, came with a CD, featuring tracks from artists that had been covered in some way—a feature story, or a blurb, within the issue.

This is how I was introduced to “Verti-Marte” by The Twilight Singers—a strange, sprawling, kind of playful or coy centerpiece to the group’s debut full-length, Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, released in September of 2000.

When was the last time you blindly bought an album.

When, if ever, was there a time when you walked into a record store and picked up an album, and based on the cover art, or the band’s name, or the song titles, knowing nothing about what it might sound like, and purchased it? And if you did that—if you’ve had this experience, how often did it work out in your favor.

“Verti-Marte,” as a song, is unlike anything on the rest of Twilight, As Played By, but how was I to know that. It was, practically a blind buy. A time of dial-up internet. A time when, even if there was a way to preview a little bit of the record, I, at the age of 17, was not certain how. I used to buy a lot of things blindly—an admittedly terrible financial habit, even as a teenager. Purchasing CDs based on a band’s name alone, or the prestige around the band, without knowing what was waiting for me when I would tear open the cellophane wrapper, open the jewel case, and place the disc into my stereo.

How often did this work out in my favor.

Because there were a number of times when it didn’t. Or it took time. It wasn’t immediate. Some of it I was simply unable to make a connection with. As I aged—moving out of my teenage years, it took me into my 30s to understand that there were things I was just not ready for.

How often did this work out in my favor.

I don’t remember anything else about this potentially electronic-based music magazine. I don’t remember any other songs from the sampler included with the issue I purchased. I vaguely remember the story about The Twilight Singers, featured on its pages. And there is the song itself.

And that was apparently enough. It was enough for me to look for Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, with great intention, at a big box music and book store in the next largest town over.

To find it, among the racks labeled “rock and pop.” To pull cash out of the wallet connected to one of the belt loops by a long metal chain.

And to purchase it.

*

And it did take me 25 years to—well, not to figure it out, but I suppose to have a better understanding and therefore a little grace, about why of the five full-length studio albums Greg Dulli released under the Twilight Singers moniker, Twilight, As Played By is the only one that sounds like it does.

It’s something I hadn’t put together really. But it makes total sense—specifically making sense in listening to the album analytically for the first time.

And there is of course a compelling backstory to Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers—I suppose the easy way to describe it is that, originally, it was a group, and an album, conceived out of frustration.

It, of course, is not as well documented, or as factually accurate, as it perhaps might be if this were all to have happened more recently, but the story goes as such—in 1997, while his band, The Afghan Whigs, were in a dispute with Elektra Records, Greg Dulli entered into a New Orleans recording studio with Harold Chichester of the alternative rock outfit Howlin’ Maggie, and Shawn Smith, the vocalist and pianist of the Seattle-based groups Satchel and Brad.

Because of the dispute with his label, it is speculated that Elektra Records was responsible for somehow leaking the songs recorded during these sessions onto the internet—there was a time, when the internet was a little easier to use and a little more fun to spend time on, and in that time, you could find the crude and unmastered versions of many of the songs that would, eventually, go on to be included on Twilight, As Played By. I hesitate to say traces of these recordings, nearly 30 years old now, have been scrubbed completely, but they are not as easy to locate today.

The Afghan Whigs’ dispute with Elektra ended with the group leaving the label, and signing a deal with Columbia—the New Orleans sessions with Chichester and Smith were shelved indefinitely, and in 1998 the Whigs released what would, at that time, be their final album—1965.

The Afghan Whigs officially split up in 2001, a number of years after a tour in support of 1965 had concluded. In the interim, Dulli found his way back to the Twilight Singers sessions, and presented the unmastered material to David McSherry and Steve Cobby—the English electronic production duo File Brazillia, who went to work reshaping the songs. In this new, revised form, the album was released through Dulli’s connections with Columbia Records, and he assembled a touring version of The Twilight Singers, taking the songs on the road.

It took me 25 years to have a better understanding and a little more grace when giving consideration to why, out of the five full-length albums Dulli released with The Twilight Singers, only Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, sounds like it does. What I realized is that there was, I think, only supposed to be this one album. And maybe The Twilight Singers, as a trio, as initially conceived, was not intended to tour, or become a “band” in the more formal or rigid sense. A project maybe. Side project. Whatever you want to call it.

But following the lengthy gestation process between when the material was recorded and when it was released into the world, there were perhaps expectations placed on Dulli to promote it, so The Twilight Singers became a more proper band, and from there, it continued to evolve.

I often think about a brief email exchange I had with Shawn Smith when I was in college—it was around the time he was launching an online store in conjunction with the release of his second solo album, Shield of Thorns. There was a delay, I think, in when the store was going to be up and running, and I had inquired as to whether I could just pay him directly somehow, and he could put a copy of the album in the mail. During our conversation, I had off-handedly asked if there was another Twilight Singers album in the works.

He responded, “Greg didn’t ask me to be a part of the next Twilight Singers album.”

I suppose you could describe The Twilight Singers, then, during the group’s active years, before Dulli retired the moniker in 2012 and revived The Afghan Whigs in 2014, as a collective with a revolving door, where he was always front and center, with an aesthetic that remained dark, or moody, sure, but quickly shifted from the textured, electro-infused production and acoustic, inward, and at times R&B leanings, to a much more straightforward “rock” or guitar driven sound that he, as band leader, rarely if ever strayed from.

The story goes as such—near the end of 2001, Dulli began working on a second Twilight Singers album, the working title of which was Amber Headlights¹. At the start of the new year, his longtime friend, filmmaker Ted Demme, had a heart attack and died on a basketball court, and Dulli, wracked with grief, never returned to the songs he had been working on up until that point.

Instead, after finding inspiration from the Jack London novel Martin Eden, he began working on what would become the second Twilight Singers album, Blackberry Belle, which was released independently in late autumn of 2003.

Dulli would release three more full-lengths between 2004 and 2011—the oddball, uneven covers collection, She Loves You, in the summer of 2004, the Hurricane Katrina-inspired Powder Burns in the spring of 2006, and then the project’s final bow, Dynamite Steps, at the beginning of 2011, each record moving him further and further away from the complexities and nuances, and the overall hush, of the project’s debut.

He resurrected The Afghan Whigs, a beloved act or at least a long-revered name, in 2014, and has released three albums with this configuration of the group, which at this point includes only one other original member.

*

Rock steady, baby. Your man is dead

And if you will allow me, as I often find myself asking you, the reader, I wish to break the fourth wall, at least momentarily. Because in writing about music, and in writing about music the way that I have chosen to do, specifically over the last five or six years, is that I do want to work towards something as I take you through my experience with the album.

I, of course, write myself into these as a character, and I am always working towards realizations about myself, and in doing that, I often structure these as such, so that my analysis of the songs I have the most personal attachment to, or are, for lack of a better description, my “favorite” or the moments that I consider to be the finest, arrive near the end.

It is a formula. I understand that. Perhaps it is a little cloying. Or a little much, once it finds its way onto the page. But this is the voice that I have adopted, over time, and I tell you all of that to tell you this—Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers is an album that is intentionally bookended by its two most well assembled, or “finest,” or most genuinely interesting moments.

The depictions of toxic masculinity, among other things, in the film High Fidelity, have not aged well, certainly, but something from the movie that I am often giving consideration to, comes from one of the "top five” lists that the characters are often quipping about throughout—specifically the list of Top Five Side Ones, Track Ones², because I am confident the opening track from Twilight, As Played By, the recumbent, brooding, gorgeous “The Twilite Kid,” would be amongst my selected five.

Dulli, for a number of years, and perhaps he still does, had a kind of cinematic adjacency to what he was doing, or at least I think he liked to consider himself having a cinematic quality to his work, or that he was an auteur of sorts—in the liner notes, he would say that an album was “shot on location” in specific cities, as opposed to being simply recorded. And in thinking about his output at the end of the 1990s, and into the 2000s, Twilight, As Played By is an album that lends itself to a kind of larger, cinematic scope.

“The Twilite Kid,” specifically, because rarely do you hear an opening track so luscious and so grand in how it intentionally unfolds and builds while still maintaining a moody, reserved smolder.

What I understand is that a six-minute opening track is a big ask—and what I have come to understand, in listening to this album analytically for the first time, rather than someone who has simply enjoyed a large portion of it for well over two decades, is that there is a self-indulgence to “The Twilite Kid.” Not only because it runs as long as it does, and moves at the very gradual pacing it has, but it also meanders. There are lyrics, yes, and there is a structure, but there are also lengthy, instrumental breaks where the song is given room to breathe, sure, but it also seems to prolong the arrival at its gentle conclusion.

Regardless, it is still impressive—the tone it strikes, and the tone it manages to sustain. It isn’t a song that is indicative of what’s to come. Not really. So unlike many opening tracks, “The Twilite Kid” isn’t a thesis or mission statement for Twilight, As Played By, but it is, like, a welcome. And it is an enormous one at that.

There is something that is still incredibly effective about the opening notes of “The Twilite Kid.” The song takes the first 40 seconds to slowly gather itself before the percussion kicks in, and Dulli mumbles the opening line. It is grand. Not grandiose. But just. There is something majestic about how the elements within the first few seconds, are already working together, and the stirring sensation they provide. The opening twinkles of the piano keys. The first strums of the electric guitar. The thick, rumbling bass notes that surge through everything—not overpowering but, like, extremely present in a way that is surprising. All of the pieces coming together to make this perfect music moment.

The percussive elements of “The Twilite Kid,” and elsewhere on the album, are worth mentioning. The liner notes for Twilight indicate that the drumming, at least in a number of places on the record, are the result of the remixing and production process that involved Fila Brazillia—the duo’s Steve Cobby is credited as playing drums, but in a place like “The Twilite Kid,” there are these fascinating post-production textures added to them where they are clipped, or chopped up at times, but elsewhere, they do sound more organic.

As the pieces to the song gather, and hushed, eerie, wordless singing can be heard, a quiet beat comes in, and all of these things build slowly until a skittering, breakbeat adjacent drum fill arrives, signifying, like, the true start of the song.

Even though it does, arguably, meander, especially in its second half, when there is a long instrumental break that allows Shawn Smith play a woozy solo on the acoustic guitar, it is impressive how the song remains so steady and just continues lurching forward—the rhythmic strums of Dulli’s electric guitar, with low undercurrents of synthesizer rippling in, and flourishes of the piano that enhance the overall reserved, melancholic nature of the song, continuing to swirl and coast, never really rising above a certain level, before it naturally begins to slow itself down for the final, dramatic notes that ring out into the ether.

And there of course always has been a darkness, and a bleakness to Dulli’s lyricism, and a kind of anguish. Perhaps an instability. Or a fragility. We contain multitudes, so he can certainly write songs about heartbreak, but he also has, throughout his career, possessed a kind of lusty swagger that regularly appears, creating a fascinating juxtaposition within the songs. Comparatively there is a lot less swagger here, on Twilight, than there is in his work with The Afghan Whigs, or even subsequent Twilight Singers albums. Something I realized during this listen—hearing the album truly analytically for like the first time, is how much religious imagery is written into these songs, and throughout, there is a kind of fragmented, indirect approach to a lot of what Dullli has penned—at times, lusty, yes, it is an album steeped in a kind of an eerie mysticism and an impending sense of loneliness.

“The Twilite Kid,” as it continues moving forward, is a plea to an off-stage character, and it begins with a compelling, alluring, and off-putting opening line. “Rock steady baby,” Dulli sings quietly, his voice smooth. “Your man is dead. Be careful, sugar, of who you call a friend, ‘cause they’ll get you in the end.”

The tone, though, as the song continues, becomes a little less foreboding, and Dulli wanders not into a lustier territory, but one that is more romantically inclined. “But I ain’t never gonna see you again,” he proclaims at the end of the second verse. “I’m never gonna feel you again. So let this moment never end.”

In the kind of conflicted nature of the lyrics to “The Twilite Kid,” the plea, and a sense of regret, but not remorse, come in during the chorus. “And if my love, I said ‘I’m sorry,’ would you believe me? Should I cry,” Dulli asks, before adding the stark, “Then hold me as I die.”

*

And I think there is, perhaps, still a misconception about how The Twilight Singers worked—or how it began, unassumingly, and then shifted. I say that, given my own experiences with the band, or the project, or whatever you want to call it, since sitting down with Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers the first time, at the top of 2001, and how my perception shifted now, in listening analytically.

And I say that because in attempting to find more information about the early incarnations of these songs—some of which were included on a lavish vinyl boxed set released in 2023, I found a Rolling Stone review of that collection, Black Out The Windows. Outside of it being a little glib, or intentionally snarky in the language it uses, it erroneously states that in the interim between Twilight and Blackberry Belle, Chichester and Smith “exited” the band.

I keep thinking about the brief exchange I had with Shawn Smith, when I was in college. “Greg didn’t ask me to be a part of the next Twilight Singers album.”

I never thought that Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, was, like, a perfect album. It is heavily flawed—there are songs that are not unlistenable, but they are not as well executed, and in how they land, ultimately bring the pacing of the record down. But in listening, for the first ice, through analytical ears, what surprised me was just how little Chichester and Smith are ultimately involved, or present, in how the final product sounds.

I mean, it is honestly very apparent if you listen closely—both Shawn Smith and Harold Chichester have extremely unique voices. But in referencing the liner notes of the album’s proper 11 tracks (there is a short, instrumental piece that plays prior to the stunning penultimate song, “Into The Street), Chichester and Smith are not included in the personnel for five of them.

It is interesting—genuinely interesting, to think about how The Twilight Singers work as a core trio, because those songs, where you can hear Dulli, Chichester, and Smith, and they are all making enough space for one another within the atmosphere of the song—it is those moments that do work the best, or are the more compelling of the set.

And part of what makes them the most compelling is that they are so diverse—the trio really containing multitudes.

Something that I kept coming back to, and it is a very idiosyncratic way to describe at least some of the songs on this album, is a kind of amalgamation of trip-hop and more gentle, acoustic sounds you would perhaps hear in a coffee shop. On paper, it sounds like it might be an absolute disaster, but at least in the first two songs on the album, and near the end, they pull it off impeccably.

There is a hint of spiritualism, or mysticism, in the album’s second track—the acoustic, shuffling groove, “That’s Just How That Bird Sings.” Certainly in its lyrics, yes, but also in the instrumentation used. It’s sparse, or, at least, it is a lot less layered comparatively, but there is still a lot happening with the way both Dulli’s and Chichester’s acoustic guitars swirl and intertwine, and the subtle plinking of the kalimba, and the additional strums of an oud, and the driving thuds of the tabla.

The song, structurally, does not work in a round, exactly, but there is like a circular feeling to the group leads it through the verses, and then allowing the instrumentation a pause as Chichester finds himself in the place here he delivers the titular phrase, with the music, then, coming back with a small, dramatic flourish.

Dulli, Chichester, and Smith take turns delivering specific lyrics—something they also do on the subsequent track, “Clyde,” and on the album’s stunning closing song, “Twilight.” It feels organic, here, though—it isn’t like the three of them are not really in the moment, of the song, just waiting for their turn.

Lyrically, there is a fascinating contrast that occurs between “The Twilite Kid,” and “That’s Just How That Bird Sings.” The kind of muted, sardonic pleading has been replaced with vivid imagery, at times cryptic, that flows forth from each voice. And, I mean, some of it is a little cloying, but it, like the album overall, I think, is really trying to conjure a vibe, as a whole—the lyrics aren’t meant to take a backseat or anything, but they are not meant to be scoured over for a deeper, analytical meaning.

And even though it is all a little ambiguous, there is something vivid in these phrase turns. “Seen the morning light—it breaks the sky to the east,” Chichester proclaims in the opening line. “Hear the birds above announcing the light, like rays of love,” he continues, before Dulli slides in. “Hear the one who sings, as darkness clouds the western sky,” he contends soulfully. “The one who sounds as though he’s weeping for his long-lost lover.”

Smith’s voice is heard third and of the three, I have alway considered him to be the most genuinely interesting in terms of his range, and delivery—there can be, and often is, a gruff quality to his voice, but when he is heard throughout Twilight, and yes he is often just contributing backing vocals, or ad-libs to punctuate, he pushes his voice into a pristine and fragile falsetto, which is how he quietly sings his contributions here. “He’s alone and sad,” Smith observes. “He betrays the bluest sounds coming down over the rooftops, into your dreams,” he finishes, before handing it off to Chichester. “That’s just how that bird sings.”

*

There are a lot of things that haven’t aged well about the lyricism of The Afghan Whigs—there is this wounded toxicity that is difficult to hear, today, and not grimace or raise an eyebrow at how Greg Dulli portrayed himself, his broken heart, and his tumultuous relationships. The contrast of that was Dulli as a lothario—because even with his heart broken, there are a number of songs that are sexually charged.

Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, is not a lusty album. Maybe there is a little undercurrent of sensuality at times, but the only place where it does teeter into a truly sexually propelled nature is on the unrelenting third track, “Clyde,” which is based around a thundering, hip-hop slanted drum beat that literally never lets up from the moment you first hear the kick drum rumbling.

“Clyde,” musically, is another place where it seems like, if you were to write out a description of how it sounds, that the results would be disastrous—because over the top of that deep, groove oriented beat, along with a very thick, rolling bass line, are the flairs and pulls from a sitar—again, giving it this mystic, spiritual sensation, which is juxtaposed something designed to rattle the subwoofers in your trunk.

The song rarely deviates from this structure—and, I mean, in a sense, “That’s Just How That Bird Sings” is similar, and both of which are rather hypnotic in a way, the way they conjure this atmosphere.

The interplay between Chichester and Dulli is fascinating to watch as they take turns delivering the lyrics on “Clyde,” which Dulli leaning into an almost lecherous persona towards who he is addressing—self-aware and satirical in how he oozes lines like, “Babydoll, why you leaving? Come upstairs and get high with me,” or in the second verse where he utters the line, “Shot dead by you again,” while the sound effect of an explosion rumbles underneath him.

Chichester is much more earnest, or at least tactful, in how he addresses this off-stage character. And, I mean, Dulli does come around, by the end, to a slightly less sleazy phrase turn when he confesses, “Nobody ever touch me before like you did, but you won’t do again,” but his counterpart on the song takes a more poetic or romantic approach. “The time is nigh for us to fly,” Chichester exclaims early on in the song. “Take you where there’s no sorrow. Time is right, and time is invisible if you’ll come with me.”

“I smell a sweet fragrance about you,” he coos later, before becoming a little more forward and suggestive. “And I know that you want it too. So if I trip and lay one heavy on you—please forgive me.”

Like the hypnotic nature of the music itself, the chorus to “Clyde” works similarly in its use of repetition and rhythm, and a kind of swaying and swelling of slightly overlapping vocal layers. “You’re making me want it so what I feel inside, I can’t deny,” Dulli and Chichester sing, while Smith, in this song, while responsible for the drum programming and the heavy, rumbling bass notes, is relegated to the role of a hypeman of sorts, continuing to ad-lib and echo specific phrases subtly, using his higher range.

Even in how self-aware and lusty it is, and unlike anything else on the album in terms of how it sounds and what is at the core of its lyrics, “Clyde” is a fun song—which is a surprise, given how, really, Twilight is not really a “fun” album. And with that being the case, it is one of the few places here where it sounds like Dulli, Chichester, and Smith are having fun while assembling it.

*

In how Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, is structured, I think something that I perhaps always knew, but in high school, and even in college, I did not have the vocabulary to articulate, was that it is just all over the place. But, maybe, that was unavoidable, just given how some of this material was recorded, and then shelved, and then re-approached with what ultimately was a different pair of collaborators.

I think its unfocused nature, or the cohesion it lacks at times, also comes from Greg Dulli himself, and where his interests lie, or rather, what influences him. The Afghan Whigs, even though they were from Ohio, and one of the first non-Pacific Northwest bands to sign to Sub Pop, had a grungier slant to their kind of alternative rock early on, but the further into their carer, before splitting at the end of the 90s, you could hear more of his interests in R&B being folded in.

The place where that is the most prevalent or apparent on Twilight is within the second half, on the very smooth, soulful “Railroad Lullaby,” which is one of the songs that does not feature the contributions of Chichester or Smith, and musically, it is one of the more relaxed or easier going songs on the album, falling into a slower, slinkier groove from the moment it begins through the way the layered instrumentation works together.

“Railroad Lullaby” tumbles together gently, and never really rises above a certain level in intensity. It’s held together by a subtle, jazzy kind of percussive pattern that skips and skitters, while the warmth of an organ-adjacent keyboard sound, and a textural tone that shifts between different chords, quickly creates an infectious environment which, the more time we spend within it, lean into the B of R&B, through mournful electric guitar chords, some slight piano key tinkling, and given its title, it is fitting that a harmonica makes an appearance while Dulli quietly sings his lonely lamentations.

“Do you remember when I told you that I had a tale to tell,” he sings, almost as a warning. “Let me regale you, child, about a life spent on the rail.”

There is an implied weariness to the song’s theme, and admittedly, I would content that the metaphor is a little heavy-handed, in how Dulli, even in the few lyrics sung within the song (it, as other songs before it, spends a lot of time in the hypnotic rhythm of an extended chorus), uses the ragged notion of traveling by railroad as a stand in for the hard lived life of a musician.

Dulli’s reputation, I think, has always preceded him, dating back to the earliest days of The Afghan Whigs, up until 2006, with Powder Burns being the first album he worked on after quitting his longtime cocaine use. His dependence on hard drugs and alcohol fueled a lot of his debauched depictions in his lyricism, and “Railroad Lullaby” serves as an acknowledgment of that, and the toll that it takes.

“Whenever the drugstore man used to come around,” he confesses in the second verse. “I’d bite my lip and then I’d take myself to town.”

The chorus to “Railroad Lullaby” hinges on the hypnotic slink and reputation of the specific phrase turn, which, for as catchy as this moment in the song is, and the kind of groove that everything falls into, is ultimately bleak if you think about it too long. “Forget me not—don’t forget it,” he sings quietly. “‘Cause I’ll be gone in a minute.”

That bleakness then, effortlessly, fades into a kind of hopeless resignation both in the final verse, as well as an extremely isolated consolation that Dulli adds into the chorus. “Now you say the train’s a coming, but I don’t see it on the track,” he exclaims. “Last train’s 11 and it ain’t coming back.”

“Nobody ever needs you when you’re gone,” he laments, as the song finds its way to a conclusion. “When you’re this far gone.”

*

I don’t remember the name of the magazine. You think I would with the kind of information I tend to retain. It would have been a music magazine though and potentially one dedicated to electronic music and I would have bought it at the bookstore in the small, rural, Illinois town I grew up in, either at the very end of 2000, or at the start of the new year. And the magazine, as many music magazines at the time did, came with a CD featuring tracks from artists that had been covered within the issue.

The track from The Twilight Singers included on this CD was the sprawling, playful, coy, and kind of strange centerpiece to Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, “Verti-Marte,” which is unlike anything else on the album, but a 17 year old version of me found the track to be interesting enough, and the blurb, or story about the band, to be compelling enough, to purchase the album.

Dulli would do this elsewhere in his work with The Twilight Singers—his cover of Hope Sandoval’s “Feeling of Gaze,” which opens the group’s 2004 album, She Loves You, begins with the snippet of a voicemail; and the slow burning, tender “The Lure Would Prove Too Much,” which is arguably on of the group’s best canonical songs, from the Stitch In Time EP, layers a number of different voice messages throughout its second half, into its cathartic conclusion. I mention all of this because “Verti-Marte” is based around both a repeated, loose, rhythm that is slow to build, and around the layers of conversation snippets between Dulli, and Sophia Da Silva.

There is a voyeuristic quality to it, honestly. The way different bits of dialogue are snipped, out of context, and placed within the song—repeated, and slightly overlapped to create a bit of a disorienting, and yes, cinematic effect. What is most interesting, I think, in how the conversation snippets are used, and sequenced, is that it does run a cavalcade of emotions—there are moments, like at the beginning, where Da Silva cackles, her accent heavy, and this is where it is coy, or playful, as is when she asks, “Oh, what are you smiling at? Oh, what are you writing?”

The tone, though, even as the music grows and slides towards the very danceable groove it lands on, with sharp, spaced out percussion, and warm ripples of keyboards, is ever shifting though. “What is salvation,” Da Silva asks at one point. “Salvation is when you are saved,” Dulli responds, before laughing a little. “I obviously don’t know what it means.”

“Verti-Marte” is, as it swirls and unfolds, more or less an instrumental, but it becomes more self-aware in how it uses one specific conversation snippet and how it uses it throughout. And even though it repeats the phrase as a means of, I think, getting a laugh from the listener, it does also create this icy feeling of loneliness, which is magnified by the way the samples are layered in a disorienting way.

“Goodbye, motherfucker,” we hear Da Silva utter. And it’s subtle, but there is, like, some real aggravation in her voice when she says it—the feeling of which grows as it is the last thing we hear. “Verti-Marte” ends with a beautiful string arrangement, and her voice, looped, slowly echoing out cavernously into the distance.

*

Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, is assembled in a way with its obvious bookends. “The Twilite Kid,” and its counterpart “Twilight” are not, like, mirror images of one another, nor are they inverses of one another. They do strike a similar tone, if anything, and are both the most apparently grand or gently dramatic-sounding songs included. The kind of tunes that are crafted with the intention to be specifically sequenced within an album’s track list.

There are less obvious bookends, though—and again, not mirror images, or inverses, but definitely songs that share similar qualities, though one is more arresting in its affect than the other. With the mysticism slanting acoustic shuffling of “That’s Just How That Bird Sings” placed second, the similarly mystic, or spiritualistic and hazy in tone, though exponentially more haunting, and somber, acoustic “Into The Street” is the album’s stirring penultimate moment.

“Into The Street” is preceded by a minute-long instrumental piece, “East 17th,” that, as it is fading out, we hear Dulli’s voice whisper with emphasis, “All are punished.” The contemplative sounds of a tightly plucked acoustic guitar, and Chichester’s mournful, wordless singing come in immediately after, and “Into The Street” pulls us quickly into a kind of heavy overcast sky—walking the line between being gorgeous but also spectral, and melancholic.

In terms of how it is arranged, “Into The Street” relies heavily on the kind of otherworldly, etherial atmosphere it creates through the string accompaniment, and a slight, chilling echo that coasts off of everything—the only other instrument we hear is the acoustic guitar, so it really is up to the big swells, and eerie low ripples of the cello and violin, working together, to keep things moving forward, and in its inward nature, to keep it both moving forward and compelling to hear as it slowly tumbles and unfolds.

Shawn Smith is notably absent from “Into The Street,” so the interplay occurs only between Dulli and Chichester, who trade off sections in the verses, and then come together for the chorus—walking a kind of fragile tension in how they sing this gently together, with Chichester’s range getting the chance to soar later on, not as means of, like, stealing the show, or one-upping his bandmate, but of taking the song to the height it wishes to ascend to before it swirls out into silence.

There is still a poetic, or literate nature to the lyricism here. I am hesitant to say that it is more direct or a little less vague when it is compared to a song like “That’s Just How That Bird Sings,” but if anything, it is just much more vivid, or palpable, in its choice of words, and the portrait it creates.

“One early morn,” Dulli begins quietly. “I couldn’t sleep. I poured myself into the street.”

“I watched the world from off a cloud,” Chichester adds, as less of a response and more an observation. “I saw the people quarreling out loud.”

And there is, throughout the album, a kind of lingering sense of loneliness. A sorrow. Or an isolation of sorts—this becomes apparent the more time we spend in the world that “Into The Street” is crafting.

“Shut out the lights, turn down the bed,” Dulli commands in the second verse. “Whatever gets you through your head,” he adds, before he’s joined by Chichester. “Unlock the door, throw away the key—we don’t want the spirits watching as they hover over you and me.”

That shift into sorrow, and isolation, feels more emergent, or inescapable, by the time the song arrives at its third verse, which Dulli sings, with Chichester echoing the lines just behind him, giving the song an even woozier effect. “My little girl, where did you go?,” they ask, together but separately. “I cannot find you anymore. Angel sweet. Angel bright. Come on back to me,” an attempted assurance is made. “I promise you, the wall will fall with me.”

Pleading, or a kind of desperation, is present certainly elsewhere on Twilight. It is, in many facets, a hallmark of Dulli’s lyricism—once often fueled by substance use and lust. “Into The Street” is missing both of those elements but there is this terrible, sad longing that the song arrives at just as it soars and then makes its final descent into a conclusion. “So sad, the wind—a brighter day will come again,” both vocalists remark early in the song, in a moment that serves as a pause between verses. “The way I’m going down. This time, this time, I’m going down,” they sing with immediacy in the final moments. “I can’t fight. I’m going down,” they say, before Chichester howls a solitary “Goodbye.”

And there are moments on Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, where the lyrics are of importance, but it is an album that does primarily work to craft a specific feeling, or vibe, from song to song. “Into The Street”’s writing is so shadowy, but in being shadowy, it is also so precise in the feeling that it creates, and set against this sparse, ghostly backdrop, it is still one of the more breathtaking, lingering moments on the record—both when I first heard it, so many years ago, and even with the familiarity I have with it now, and how it rises and falls, I am still compelled by it, and still plunged into the heavy, cloudy gray sky and desolate street it pulls us into.

*

I keep thinking about the brief exchange I had with Shawn Smith, when I was in college. “Greg didn’t ask me to be a part of the next Twilight Singers album.”

And if you will allow me, yet again, as I often find myself asking you, the reader, I wish to break the fourth wall one more time. Because in writing about music, and in writing about music the way that I have chosen to do, specifically over the last five or six years, is that I do want to work towards something as I take you through my experience with the album.

Or, at least, in this case, I need to take you through my experience outside of the album.

And this is a story that I have, most certainly, told before. About Shawn Smith.

At the end of a calendar year, as the next is on the horizon, I give consideration to important records that will be celebrating a milestone anniversary—my intention, in doing so, is to find the time to write about as many of them as I am not only able to, but would behoove me to spend time in, and with, and that the result would be exciting for me to write about, and compelling for someone to read.

The intention is there, but for myriad reasons, I find I can only really take on a few from the list every year, before the autumn becomes the winter and it is time to look ahead yet again.

I tell you all of that to tell you this—last year was the 25th anniversary of Shawn Smith’s debut solo album, Let It All Begin, and I did have every well-meant intention to spend the time needed with it, and not only write about it, and how diverse of a collection it is, but about my long history with Smith’s music, spanning all of his projects, both well-known and not.

Last year was also the fifth anniversary of Smith’s passing. He died on April 5th, 2019.

And this is a story I have, most certainly, told before. So I apologize if you have already heard it.

I need to take you through my experience outside of the album.

And because I have already told this story before, I will try, as I can, to be brief in this retelling.

My first job, when I was 16, was at a drugstore—a CVS equivalent, something colloquial to Illinois. I am dating myself, as I almost always do, but this was a time when the internet moved a lot more slowly, or it was not as intuitive. This was a time before a smartphone. And before an app like Shazam. And, like, okay. I get it. I understand there is some kind of stigma to using that, to identify a song. But at the age of 16, in the year 1999, it would have been helpful.

The music played overhead at the drugstore was, more or less, the same kind of style of music, or genres of music, you would hear in a grocery store, or department store, today. The same things—often things I did not much care for—would be overplayed, or played with more frequency, and occasionally there would be a song of interest, or of note.

One of those songs was “The Day Brings,” from the 1997 album Interiors, by Shawn Smith’s band Brad. It would take me over two more years to put that together, though. It would take me well into my first year of college, combing Audio Galaxy—a post-Napster file sharing service that had not been outlawed on campus yet, and honestly just downloading anything, and everything, onto the desktop computer of the girl I was romantically involved with at the time.

For all the things that I do remember, or have retained, a detail I cannot recall is why I would have even been looking into The Twilight Singers, or the other projects of its members—attempting to find tracks from Harold Chichester’s band Howlin’ Maggie, I think, was difficult, and I seem to remember downloading a lot of material from The Afghan Whigs.

This was at a time when for as clunky or as rudimentary as it might have felt, the internet was a little more fun of a place. So it was easy, and felt harmless, to download live, often poor quality bootleg recordings from the handful of Twilight Singers performances that had taken place in 2001, or the early, unmastered recordings of the New Orleans recording sessions that had found their way onto the internet years prior—they were new to me.

For all the things I do remember, or have retained, a detail I cannot recall is why I would have been looking into The Twilight Singers, or the other projects of its members. But in looking up Shawn Smith, I found both his solo album, Let It All Begin, as well as a live album he had released shortly thereafter.

Among the songs that I downloaded from Smith’s live album was a song called “The Day Brings.”

This was when I put it together, you see.

Smith fronted two bands throughout the 1990s—Satchel, which released two albums before becoming more or less a dormant project until it was briefly resurrected in 2010, and Brad, which gained a little more attention or more listeners because of Pearl Jam’s Stone Gossard, who played guitar with the group.

Certainly a cult artist, and certainly a voice responsible³ for songs you more than likely have heard, Smith, even with these brushes with more mainstream or wider success as a singer, never could transcend a kind of obscurity. There was a time, certainly more than five years ago, when Smith had launched a pretty barebones website, and on it was a quote from Greg Dulli, who referred to Smith as “Seattle’s Best Kept Secret.”

I always think about the brief exchange I had with Smith, when I was in college, when he told me, “Greg didn’t ask me to be a part of the next Twilight Singers album.”

Beginning last year, at the fifth anniversary of Smith’s passing, his estate began, for the next calendar year, issuing unreleased material on a Bandcamp page every Friday—Smith was, especially in the early days of using the internet to self-release music directly to fans and listeners, extremely prolific. And near the end of 2024, a song recorded during those New Orleans sessions was released—“Glass of You.”

Rough and unmixed, the song also appears as part of the rarities collection featured in the career spanning Twilight Singers vinyl boxed set—rough, and unmixed, and it’s funny, because at the start of 2002, through headphones plugged into the bulky desktop computer, I had presumed the quality of the mp3 I had downloaded was just low. But no. I mean, sure, it was. But the recording of “Glass of You” that exists is also just not very clear or balanced.

“Glass of You” would not have been out of place, exactly, on Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, but it would have had to have been a version of the album that was never given a chance to exist, because it most certainly does not really fit with the version of Twilight, released in the year 2000—an album that, the longer you spend with it analytically, the more you understand where it really lacks cohesion, and how it does try to cover that up, or distract from it.

From the songs that survived the original recording session, none of them are, like, solely structured around only one member of the Twilight Singers operating as a trio. So in that sense, “Glass of You” is genuinely interesting because it does feature Smith on lead vocals, and from what I can tell, in listening closely to the still rather rough audio, Dulli and Chichester are not present—or, rather, are not present vocally.

“Glass of You” is intentionally slow—not, like, a trudge or anything, but it is deliberate in how much time it takes, and it is incredibly somber in how it sounds. It opens with an effected electric guitar, strumming contemplatively, and single bass notes throbbing through underneath, while the subtle sounds of an electric piano can be heard, twinkling through, and the faint tap of a cymbal, attempting to create a tempo for the song to follow. And that’s the thing about this song—and this song being what is more or less a demo recording, or a first take. It is full of imperfections, which make it a real snapshot in time.

As “Glass of You” continues to slowly unravel, it never really gathers more momentum, or pushes itself out of this melancholic holding pattern—only lifting slightly during the chorus, when the slightest brush of a snare drum comes in, quickly disappearing when the song descends back into its verses, repeating the same chordal shifts, striking a heavy, lonely kind of tone.

One of the imperfections is how quietly Smith sings—his voice is not only buried in the way the song is mixed, but also he is just mumbling his vocals at times, or seemingly stepping back from the microphone so they are not picked up at all. And it is a curious thing—his voice is, of the three, the quietest in how it is presented on the final version of the album. And so it is, at times, a little difficult to understand his lyrics completely, his voice gentle, a slight echo trailing off of him.

“Losers are winners,” he declares in the opening line. “They’re all the same. Why do we come back again and again?,” he asks. “Why does the world have so many scars? Why am I so hypnotized,” and then a slight pause, as he arrives at the repeated phrase that serves as a chorus, and turns into an incarnation of sorts. “In your eyes.”

There are no liner notes available for the song via Smith’s Bandcamp site, and the only information, or history given, is that the song was “pulled off the original album by Shawn, for reasons of his own,” and one of the imperfections—and I have no idea who contributes which instruments on “Glass of You,” but whoever is playing the guitar occasionally flubs a note, but keeps going—again, making it a snapshot in time. A moment in the studio.

The cover art selected for the digital release of “Glass of You” is a black and white photo of Greg Dulli and Shawn Smith—they’re facing each other, and it looks like they are mid-conversation. Dulli, on the right in the photo, is smiling, or at least is flashing his teeth.

I keep thinking about the brief exchange I had with Shawn Smith, when I was in college. “Greg didn’t ask me to be a part of the next Twilight Singers album.”

*

When darkness falls on summer’s end…

And I have already told you, the reader, if you will allow me just one more time to break the fourth wall, to address you more directly, that Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, is bookended by its two most well-assembled, or, yes, “finest,” or most genuinely interesting moments.

And while the album opens with the slow simmering, kind of brooding shuffle of “The Twilite Kid,” it closes not with a mirror image, or inverse, but a tonal shift into something gentle that lifts the album’s affect, as a whole, to a place that it was not struggling to reach before, but perhaps we as listeners were unaware it was stretching itself towards.

A slight flicker of hope, or optimism.

And this is not to say the album, from beginning to end, is pessimistic, or completely hopeless. But. It is an album that explores a darkness—it is not exactly an uplifting collection of songs, so it is a surprise, I think, that as it ends, we are given a reprieve from that darkness with the sprawling, glitchy, and ultimately jubilant (albeit restrained) “Twilight.”

Really, the only similarities it shares with its counterpart at the top of the record are in name and in running time—“Twilight” is a whole seven seconds longer, and as it builds, if nothing else, it becomes a meditation on assurance.

Like “The Twilite Kid,” “Twilight” does take its time as it slowly, and with intention, collects itself, quietly warming up with the mournful pulls of a pedal steel, before you hear the percussive elements coming together—it, similar to elsewhere on the album, is produced and mixed in such a way that there is this blend of both live drumming as well as beat programming and manipulation, and it is a marvel at how they effortlessly intersect—again, kind of veering into that trip-hop/acoustic coffee shop feeling that is both relaxed and propulsive at the same time, and in how they veer into it, they make it work because this kind of juxtaposition I think would fall apart in the hands of less capable artists.

There is a gentleness that “Twilight” coasts on, as atmospheric layers are added, and piano notes delicately twinkle—it never really rises above a specific level, even as it continues to kind of build, or seemingly wishes to build towards something larger. It doesn’t resign itself to this, but rather, it just comfortably remains, with the beat kind of skittering underneath it, and this sense of jubilance slowly slowly rising up towards the top. It is the kind of song that, because it is the final track, could be like, “big,” or get out of hand, especially in the way that one specific phrase is repeated at the end. If they had wanted, they could push this moment out further, but it remains steady and like a small moment of comfort and assurance.

In terms of how the lyrical delivery is split up, it is again a Chichester and Dulli song, with Smith credited in the liner notes as playing the bass and piano, and contributing understated backing vocals, which you can hear, sure, but as he does on other tracks, he gets a little lost in the mix with the amount moving parts.

The lead-up to the opening line of “Twilight” takes a little less time than its counterpart, with Dulli arriving a little after 30 seconds in, gently singing, “When darkness falls on summer’s end—so in your absence, I shall begin.”

“When darkness falls, the race is done,” he continues. “And love lives not when hope is gone.”

And I suppose like “The Twilite Kid” before it, there is this kind of ambiguous poetic nature to it—phrases that sound good, or conjure something, within the world that the song is building. It is a song that does rely on a specific vibe, or tone, that it strikes, but there is also more here, with the lyrics, or at least they do lend themselves to pushing towards a larger conceit.

I am also fascinated, and have been for a while now, with the way both Dulli and Chichester talk about time, respectively. Or times of year. Seasons. Whatever. Dulli opens his verse talking about the end of summer, and Chichester jumps ahead to the middle of December—“The longest night of every year, I spent beside you, baby,” he explains. “Do you remember anything about me? I was the one, when hope was gone, who took too long to sing this song.”

The phrase repeated, serving as a chorus, as first said, four times, and once with an extra assurance included, for good measure. “Everything’s gonna be all right,” Dulli promises. “Everything’s gonna be all right, baby—you’ll see.”

But as the song finds its way into a real groove, skittering towards its finale, the phrase takes on a life of its own—an incantation. A prayer. The more times it is said (32 additional by the end), it becomes less assuring, and maybe more like an attempt at convincing. But who. Is it Dulli, who is trying to convince someone? Or is he trying to convince himself?

Regardless, it creates this fragile kind of cathartic exhalation that you fall into, as the listener, and get wrapped up in the notion of the hope, or the optimism that the song continues to offer us.

You do want to believe.

Everything is going to be all right.

You’ll see.

*

I’ve seen Greg Dulli perform live twice—once, in early 2008, with his one-off project with Mark Lanegan, The Gutter Twins, and again in the spring of 2011, on what would end up being the final Twilight Singers tour, with the group out in support of Dynamite Steps.

Over a decade removed from Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, and on the road to promote a new release, the group’s setlist from May 2011, on stage at the Varsity Theatre in Minneapolis—it should not have surprised me that it went extremely light on material from their debut, playing only “Love” and “Annie Mae,” both of which are more products of Dulli’s work with the duo Fila Brazillia than anything originally recorded in 1997 with Chichester and Smith.

And maybe you have had experiences like this in the past. But there are times when you see an artist, or a band, perform live, and it cements within you the reasons why you like them in the first place. There have been other times, though, where you see an artist, or band, that you liked perform, and in the wake of the concert, you find yourself beginning to drift, or lose interest. It could be for any reason. Any number of reasons. It’s hard to articulate, really. Maybe it’s just a feeling. Maybe you don’t have to articulate it at all, and even if you could, you just keep it to yourself, and you find you are listening to the artist less and less, and showing less interest or enthusiasm for additional albums they release.

I felt this way about Sigur Rós. And I realize now, in giving this consideration, I feel this way about Greg Dulli and the Twilight Singers. Putting the project to rest shortly after the tour wrapped, he returned to performing under the banner of The Afghan Whigs a few years later. Still in my infancy as a music writer when their first album in 16 years was released, I remember being excited, but then surprisingly nonplussed by it, and I had not invested any time in the two subsequent Whigs full-lengths, or the solo album Dulli released at the start of 2020.

When I think about The Twilight Singers now, yes, I think about this album, and being 17 at the start of 2001. I think about the email exchange I had with Shawn Smith when I was in college. I think about the personally tumultuous time surrounding my attendance of The Twilight Singers concert in the spring of 2011, and perhaps that had something to do with why I understand now it was the place where my interest began waning.

I think about Greg Dulli, though. The person and the persona. I think about the race-baiting he had done throughout his career—his band, before The Afghan Whigs formed, was called The Black Republicans. The name “The Afghan Whigs” itself is, of course, not without a raised eyebrow. I think about the cover art to the band’s 1996 album, Congregation, or some of the song titles he used throughout his career.

I think of the way he was comfortable wandering off stage, and into the crowd, for a loosely improvised/loosely planned jam and medley during his performance at the Varsity Theatre, where he sang the first verse to Kanye West’s “All of The Lights,” not even batting an eyelash at the use of the racial epithet included.

I think of how the first song on the Whigs’ debut is titled with the r-slur.

I think about how, yes, it was years before the accusations against him were made public, but how Sean Tillmann, who performs under the name Har Mar Superstar, starred in an Afghan Whigs music video and was selected as the band’s supporting act in 2017. I wonder if Dulli is still in contact with Tillmann at all now, after it was revealed he was an egregious sexual predator.

I read an interview with Dulli from just a few years ago, when the most recent Afghan Whigs album was released. He seemed to be among the crop of artists who were bothered, or annoyed, by people thinking and listening intersectionally—he refused, in the interview, to apologize for the implied misogyny of some of his writing with The Afghan Whigs, like on the group’s 1993 effort, Gentlemen.

We continue to grow, hopefully, as listeners. In how we think. In what we believe. Sometimes the music from our lives. Other times, it does not. And we cannot take it with us.

This is something that I am always thinking about.

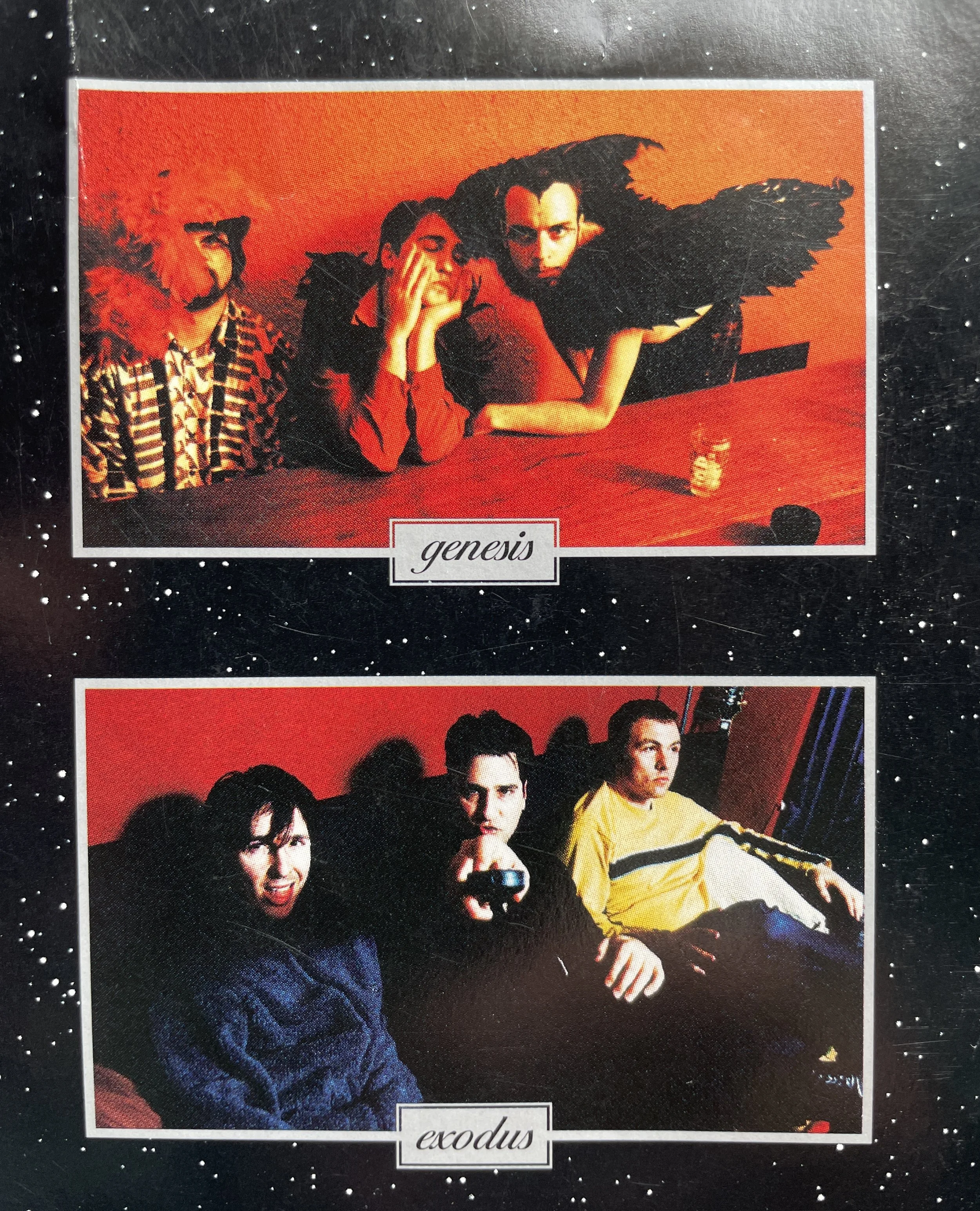

I’m pretty sure I had put this together a while ago, even before I really sat down to think about Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, analytically, but on the back cover of the CD’s liner notes, there are two photos—one features Greg Dulli, Harold Chichester, and Shawn Smith. The word “Genesis” is written underneath it. The other is Dulli sitting between Steve Cobby and David McSherry. It is labeled “Exodus.”

I am, of course, probably reading entirely too much into this, but the photos, both of them, presented this way, seem representative of someone torn between two different things, or ideas. Perhaps uncertain what to do with either of them. But also gripping tightly to both, hoping it works.

More than anything, I think, 25 years later, and almost 25 years spent with it, Twilight, As Played By The Twilight Singers, is an album that I often think about more than I am moved to listen to. Maybe you have albums or songs like that in your life, too. A song or two might make it into a playlist, but it is more representative of something, and you do not always feel compelled, for whatever reason, to revisit. Maybe you saw the flaws, or cracks, or whatever, long before you gave it some kind of critical analysis. Maybe you knew they were there, and you did not have the vocabulary to explain it.

I do owe it as my eventual formal introduction to Shawn Smith—his efforts as a solo artist, and the albums he put out with Satchel, Brad, and as part of the oddball electro-infused duo Pigeonhed.

And it is a curious album. I am hesitant to say it is a product of its time because I don’t think that is true. Simply because so much time elapsed from when it was originally conceived and recorded, when it was shelved, when it was returned to, and its eventual arrival into this world. Certainly informed by its time, or times. But not just a product of.

I don’t think The Twilight Singers, as a trio, was meant to outlast an album that was almost never released. And so if anything, it is representative of the frustrations it was perhaps originally born out of, but it is also representative of these moments. Of collaboration, at least originally, even if it doesn’t exactly feel like it in the end. Moments of something beautiful, dark, and fleeting that even if it is not as vivid as it was at one time, it does still linger, and that is worth the acknowledgement.

1- In the autumn of 2005, Dulli released a short collection called Amber Headlights, which are the songs he was working prior to Demme’s passing. At the time, as a fan, I ordered it without batting an eyelash—though save for maybe two songs on it, I did not much really care for it. And retrospectively, it is easy to hear in these songs specifically how The Twilight Singers as a project was always going to evolve away from the sound found on this first album.

2- This is just a quick aside to mention that, of course “Run Away With Me” by Carly Rae Jepsen would also be on this list.

3- Smith had at least one song featured in an episode of The Sopranos, but perhaps you also may know him, and voice, from the song “Battleflag,” and the somewhat popular remixed version of it by the Lo-Fidelity All-Stars.