Personal Essays

I starting writing, with regularity, what could be considered personal essays, at the end of 2013, when I began contributing the “back page column” to a monthly arts and entertainment publication, SouthernMinn Scene. A continuation of that column appeared on the similarly minded website, The Next Ten Words, from 2017 until 2018. Other non-music writing of a personal, reflective nature has been featured in issues of River Valley Woman and in The Wagazine.

Regularly written personal essays have been extremely few and far between in the last five years, but this space will offer a home to newly written pieces, as well as reviving things that had been previously published elsewhere.

From The Archives: I Was An Extra In A Hallmark Holiday Film

Originally published in the SouthernMinn Scene magazine in early 2016, these two archival, holiday adjacent pieces, are reflections on when a Hallmark holiday romantic comedy was filmed in Northfield, Minn.

Foreward (November, 2025)

The title ended up being changed by the time it was released. It’s called Love Always, Santa. And it’s currently available to stream a number of places. And maybe it will surprise you, or, maybe you will not be surprised at all, to learn that in the last nine years, I have not watched this film.

This doesn’t come up very often anymore, and it is a story that, like so many, I am not often that interested in sharing. But, a decade ago, a large portion of a holiday film was shot on location in my town—Northfield, Minnesota. At the time, and I guess rightfully so, it was a big deal. It is still, for some, a big deal—or of continued importance. Specifically I am thinking of the coffee shop that was used as one of the main locations in the film—every year, during the holiday season, they host a screening of Love Always, Santa; and on the wall, near the entrance, there is a framed piece of memorabilia from the film for you to look at while you wait in line to order.

But. I have not watched this film. And to the disappointment and frustration of my best friend, who thinks it is endlessly charming and fascinating that I was an extra, and had been granted access to the production of the film, I do not even have a timestamp for when I appear, briefly, on screen.

Filming took place in Northfield during January, 2016. And the movie itself was released in December of that year, originally via The Hallmark Channel. Prior to its television premiere, the film’s production company coordinated a screening in Northfield—by then, I had left my position at the newspaper and was slowly easing my way into a new job. I remember the morning after the screening (I, you may be surprised to learn, did not attend), one of my co-workers, who I did not know all that well yet, stopped mid-sentence, looked at me, and said, “Were you in that holiday movie? You were really good!”

But. I have not watched this film. I do not even have a timestamp for when I appear, briefly, on screen.

From the end of 2013, until the autumn of 2018, I regularly wrote short personal, observational pieces that were published in am monthly arts and culture paper—the SouthernMinn Scene, and then, online for a similarly minded site—The Next Ten Words. Save for the original documents on my laptop from this time period, and the physical copies of the SouthernMinn Scene I held onto, little if any trace of this era of my output still exists today.

Part of the appeal of having a website was the idea of republishing certain pieces—not rewriting or revising. It is extremely humbling to revisit my work from a number of years ago. But. It is a reminder of how far I have come, on the page, in the interim, but also where I was hoping to go, or the voice I was working towards adopting at the time it was written.

I wrote two pieces about Love Always, Santa—both of which were published in the SouthernMinn Scene. The first, “Quiet on The Set,” was written outside of my role as the “back page columnist” for the publication—it was a standalone piece that I had been asked to contribute once it was confirmed that production of the film would be taking place in Northfield. The second, “Extra, Extra,” was written for the column I had been given, “The Bearded Life.”

It is extremely humbling to revisit my work from a number of years ago. These are both, of course, products of their time—written in a contrarian, snarky voice that, a decade ago, I believed to be charming. If anything, I am grateful I no longer believe that to be true.

Quiet on The Set

An Introduction

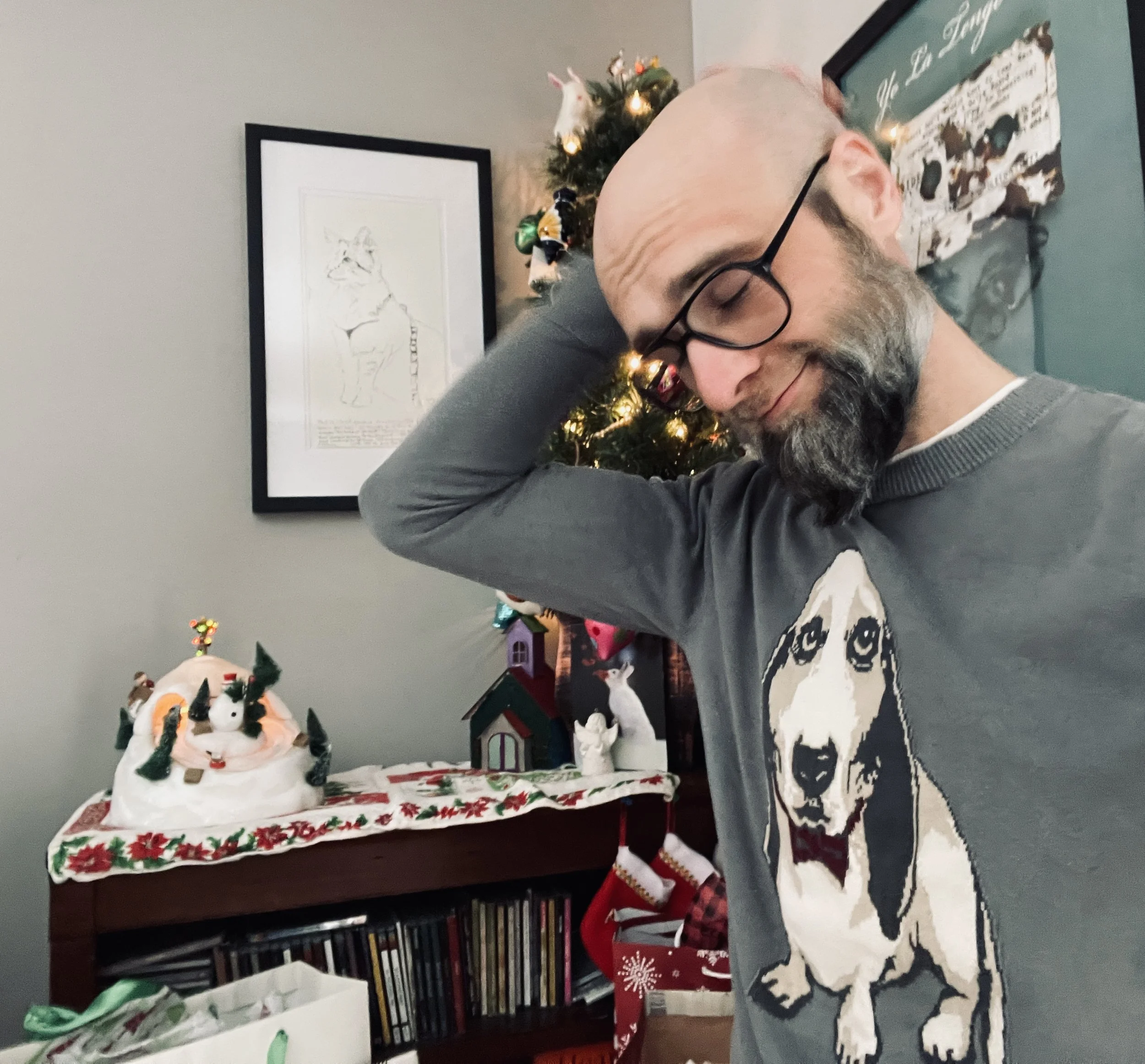

I was the guy who wore the dog sweater.

Let me explain.

The morning I meet with Mike and Lori, the producers, and with Brian, the director, I was wearing a sweater with a dog on it—a sweater I save for special occasions, like my wife’s office’s Christmas party, which I was attending later that afternoon.

The meeting was somewhat impromptu, and a topic of conversation, outside of the prospect that the trio was going to be filming a holiday romantic comedy in Northfield, became my sweater—a sweater with an illustration of a sad-looking basset hound wearing a bowtie.

This is how I became known, and identifiable in other situations, like when Mike saw me a few days later at my other job at the bookstore in town, he said “I didn’t recognize you at first without your dog sweater.” Or, later, once production was underway, Brian, after greeting me, would ask, “You got your dog sweater today? No?”

A positive way to look at this was that at the very least, I was memorable—if not for my winning personality, or my glorious beard, then for my fashion sense, or lack thereof, depending on your feelings about sweaters with illustrations of basset hounds on it.

The Movie

The movie’s called The Last Love Letter, and when I describe it as a “holiday romantic comedy,” it’s a polite way of saying that it’s going to be a made-for-television movie that will air on either Hallmark or Lifetime or ABC Family sometime near Christmas.

If you are familiar with holiday movies that air on these networks, then you’ll understand that the plot sounds very familiar—like the combination of a couple of movies that you may have already watched—A young widower owns a bookstore/coffee shop called “The Bun Also Rises.” Her daughter writes a letter to Santa, asking for her mother’s happiness (in the form of a new boyfriend) for Christmas.

The letter is intercepted by Santa Ink, a company that specializes in responding to children’s letters to Santa. The task of responding falls onto a children’s book writer suffering from writer’s block. He’s moved by the child’s letter, apparently, and writes a long letter back that this young widower reads, who then writes back to him. The two strike up some kind of letter-writing relationship (hence the title), and he travels a great distance to find her, because they are in love, or something.

And of all the locations in the world they could film The Last Love Letter, they picked Northfield—seduced by its small town charm.

The “Movies” Issue of This Magazine That You Are Currently Reading

With a tight shooting schedule for the film, the crew started production on January 11th, and were in Northfield for two weeks, filming at various locales in the downtown area.

And wouldn’t you know it, the March issue of the Southern Minnesota Scene magazine is “movies”?

And wouldn’t you know it, the deadline for content is January 29th, and that’s how yours truly ended up with this assignment, because my editor thought it would be hilarious to turn me loose on the set of a movie¹, and write something pithy about the experience, despite my crippling depression, general anxiety, overall anhedonia, and the workload that I have for my day job as a writer for the Northfield News.

“Find out what a key grip does,” he said to me, and chuckled, while I sat in his office.

Despite What You Think, I Cannot Get You A Part in The Movie

Because I wrote the original story about the movie being filmed in Northfield once it was officially announced back in early December, and because my office phone number is associated with the story on the online version, I received a lot of calls—like, a lot of calls, from people asking me how they can get a part in, or audition for, The Last Love Letter.

“Have You Ever Been on The Set of A Movie Before?”

Despite what I originally thought, name-dropping the producer and flashing my press pass does not get me onto the set right away. I have to wait to be escorted through the doors of the travel agency building by the Line Producer, Jillian. I wait in the crew’s warming tent, set up in a parking spot on Division Street. The tent smells like propane—it’s what is used to run the devices currently generating heat. It’s also where the craft services table is—a paltry smattering of cheese, little powdered donuts, coffee, and bagels that are strewn about on a card table.

Once filming has temporarily halted while people move things around and position cameras, I am quickly escorted onto the set, and am sandwiched between the end of a desk and a wall—out of the way of all the teamsters who are carrying various lighting rigs, ladders, and other equipment.

“Have you ever been on the set of a movie before?” whispers Jillian, as she scrolls through her phone, seeing there is something more important to be dealing with than a writer from the Northfield News.

I tell her that I have not, and she proceeds to point with her eyes, and expects me to follow along, to whom everyone is, and what they are all doing. I am certain that at least one of them is a grip—possibly the key grip. Though she does not identify who, if anybody, is the best boy.

At this current moment, everyone is rushing to set lighting for a scene where the male lead is reading a letter (the last love letter?) at his desk when he takes a phone call from his agent. The scene itself is probably less than five minutes in length, but has taken upwards of 15 to 20 minutes, or more, to prepare for.

Eventually, the actor, Mike, is in place, his face an unnatural shade of dark beige from all of the foundation he is wearing. As things are being finalized, before the camera rolls, I think to snap a photo on my phone—something to accompany this very story.

“You can’t take a picture of the actors,” Jillian scolds me.

I put my phone away, and never take it back out.

Coffee

“I have an odd favor,” asks Mike, the actor, to Brian, the director.

This is later, when I am sandwiched in the back of a tiny office in the travel agency—this is where the camera monitors are located, and where Brian calls action, or cut.

“Can I borrow five bucks,” Mike continues. “All my cash is in holding and I need to get a latte or something. I can’t drink any more of this coffee.”

Brian pulls out a thick, leather wallet and peels off a five-dollar bill for his actor, but then the crew announces they are ready for the next shot—the same scene they’ve been working on, just filmed at a different angle.

Mike sits back in the chair, pretending to read the same letter he has been reading, pretending to answer the phone at the desk when the assistant director says “ring ring” from off camera.

I leave shortly after this take is completed. I never find out if Mike gets his coffee.

Observing and Reporting

I find that, once people notice me on the set or are aware that I am from the Northfield News, I have to explain myself—like, what, exactly, am I doing there.

I tell people that I am observing and reporting, and that I also write the humor column for the Southern Minn. Scene magazine, and that my editor at the magazine wanted me to write something about being on the set of the movie.

I also find that even though I have a reporter’s notebook open, and a pencil in hand, I do not write much down in it, save for a tally of how many times I was asked if I was wearing my dog sweater, that I am not to take photos of the talent, and that a production assistant was, for some inexplicable reason, tearing up pieces of paper for the entire time that a shot was being set up, only stopping when it was time for cameras to roll. The sound of scraps of paper being torn and placed into a cardboard box became incredibly distracting and somewhat unnerving.

I, for whatever reason, felt this was an important detail to note.

I also note that it takes roughly an hour to 90 minutes to prepare for a scene that equates to less than a minute of screen time.

Magic

Why are we so infatuated with the entertainment industry?

That’s the question I asked myself after two short visits to the set of The Last Love Letter—once, while the crew was filming in a travel agency that was converted into the office of “Santa Ink”; the other, watching a short scene filmed in my wife’s office building.

Like, what is the allure that draws us to film, and to think that the set of a movie is some kind of magical, romantic idea?

Because from what I observed, it’s not magical or romantic. It’s mostly just a lot of people wearing carpenter jeans, standing around, waiting to move pieces of equipment when they are told to set up the next shot. Like, a lot of standing around and a lot of waiting. And then, suddenly, when it’s time to work—everybody snaps to it, and begins to hustle—holding onto their boom microphone, positioning something with the lights, touching up foundation on an actor’s face.

But we, as a culture, are captivated by the entertainment industry because of its mystique. When we watch a movie, or a television show, we don’t see the key grip, or the best boy. We see a beautiful actor hitting their mark and delivering their lines. There’s the willing suspension of disbelief that there isn’t 30 or more people, standing behind the camera, making it all happen.

For us, this is exciting. But to the assistant director, who takes himself way too seriously, barking out orders to the rest of the crew—to him, this is just another day of work.

This is what he does for a living.

And to us, it just happens to be slightly more exciting in comparison to our own lives.

A slight aside: in my original interview with Mike, Lori, and Brian, on the day I wore the dog sweater, the role of the female lead had not been cast. In making table talk with the trio at the Chamber of Commerce (where the interview took place), the president of the Chamber, Todd, said he was excited at the possibility that Danica McKellar might be in the film—the woman best known as Winnie Cooper from “The Wonder Years.” The story my editor originally was for me to try to have coffee, or something, with McKellar, and that the story would be called “My Date With Winnie Cooper.” This obviously did not transpire.

Extra, Extra

Believe it or not, my editor has the unfortunate job of fielding complaints that we occasionally receive about my monthly columns—usually they come in after I’ve used a swear word or following the time I wrote about my sister-in-law buying a marijuana cookie in Colorado.

With my January column discussing how I no longer believe in god, and February’s column featuring not one, but two utterances of profanity, I expected the conservative, delicate readers of the Southern Minnesota Scene to come out in droves to complain.

For once, I was hoping they would—because then I’d have a topic to write about for the “art” issue.

But alas—they did not. So now I have to write about my experience as an extra on the set of a movie.

You, as a reader, certainly follow along with every profanity-filled piece I write for this magazine. And because that’s the case, you are aware that last month, for the “movies” issue, I wrote a #longread about my time observing on the set of the movie that was filmed in Northfield—The Last Love Letter.

Not ten minutes after I sent my completed article, “Quiet on The Set,” to my editor for his perusal, I received a telephone call from the woman who had been tasked with corralling extras for the movie.

On the phone, she tells me that the producers of the movie like both me, as well as “my look,” and she asks me if I would like to be an extra in the movie.

Walking down Division Street, listening to her ask the question, my mind immediately goes to the place where I keep all of the excuses I would use to get out of something like this—“I don’t know if I can spare the time away from work” being the first one I use; following that, “I don’t know what my schedule is like for the week.”

The first mistake I make was telling my wife that this phone call transpired—she herself had been used as an extra when the crew filmed in her office earlier in the week. She also has an interest in filmmaking, performs in local theatrical productions, and is generally better about doing things, or showing interest in things, when opportunities like this present themselves.

I, on the other hand, thanks to my crippling depression, anxiety, and overall anhedonia, did not gaze upon this opportunity as fondly. Due to all of my…conditions…it turns out I am just not usually up for doing things that take me out of my comfort zone, or the routine that I have created for myself.

If I can quote the rapper Earl Sweatshirt—“I don’t like shit. I don’t go outside.”

Despite the fact that I don’t like shit, on a Monday morning at 6:30, I found myself outside, in below-zero temperatures, walking into the production company’s make-shift office, in what I will later discover is referred to as the “holding” area—basically, a section of the office with some folding chairs set up.

It was there I was corralled with the other extras who had been called for the day—children mostly—squirrelly, sleep-deprived children who were being wrangled by their agitated and equally as sleep-deprived parents. Children fumbling with headphones and iPads with cracked screens; children manically mashing on the touch screen of their parents’ smartphone, playing some kind of mind-numbing video game.

After sitting uncomfortably in a folding chair for an hour, we extras were all corralled from holding, across the street to where the shoot for the day was—the bookstore.

This is where I make my second mistake in this entire comedy of errors—as the director sidles up to me and we make small pleasantries, I mention to him that, outside of my work with the paper, I also work at the bookstore. As these words leave my mouth, I see the gears beginning to turn in his head—he decides he’s going to use me as a featured extra—where I am to place a sign in the window of the bookstore, advertising an in-store author event, that then attracts the attention of a child actress.

This means that I am not needed until 11:30, which means I sit around for four hours with nothing to do—save for wallowing in my anxieties about the situation. I didn’t think to bring something to do, like a book to read, or my laptop. Instead, I think about how I should be working. I wonder about if my boss will even approve the vacation time I put in a request to use so I could be here. I hope that I’ll be done before 12:30 p.m. so I can go home and check in my rabbit—something that I do, like clockwork, every weekday.

Finally, after hours of waiting and anticipation, it’s my moment to shine. A production assistant is sent over to the holding area and summons for me.

Place in the store, I am handed an oversized sign that advertises the author event, and am given little, if any direction about what to do—when I’m told, I am supposed to place it in the window, futz with it for a second, and then wave at the little girl starring in the movie.

And I do all of that. And then I do it all again. And again. And again.

That’s one of the things you don’t realize about movie making—you don’t just do something once and move on. You do it once for the camera that’s behind you. Then the crew resets, and you do it again for the camera that’s in front of you on a dolly track, moving from left to right. Then you do it again for a different camera that is also in front of you, but not moving. Then you do it again for yet another camera that is positioned slightly behind the other one.

You continue to do all this. You place the sign. You futz. You wave. The director calls “Cut. One more time.”

And it’s not just you, the director has his hands full with—he has to deal with child performers, one of whom is failing to deliver the lines in the way that he’s rehearsed with the kid just moments prior to yelling “action.”

“Say it just like that,” he tells the child.

The child does not say it just like that at all.

You reset the shot. You place the sign in the window again.

Eventually, my anxiety subsides, and I’m left with a feeling of irritation—I’m frustrated that I am still on the set of a movie, having spent upwards of six hours total in a holding pattern of waiting for this moment—the moment where I place a sign in a window and wave to a child I’ve never met, and don’t even talk to.

After enough times through, it’s determined that they got the shots they need. “That’s a wrap on Kevin,” I am told by one of the dozens of production assistants, scrambling around the set with various lighting rigs, camera mounts, and walkie-talkies.

Once I am dismissed from the set, I wander back to my office, only to be greeted with jokes from my co-workers: “Will you remember all of us little people when you are big and famous,” one of them deadpans.

Still frustrated from my morning, I laugh, because that’s all you can do.

As I sit down to begin my day—mid-afternoon—I think about the supposedly fun thing that I just experienced, and I wonder what, if anything, I got out of the experience and why I let myself get talked into it.

You reset the shot. You answer the phone, and when asked if you want to do something that takes you out of your routine, you say “no, thank you. I’m not interested.”

From The Archives: Fathering (or, There’s A Monster at The End of This Essay)

Originally written and published in 2017 on The Next Ten Words, a short, personal essay reflecting on, amongst other things, the idea of fathers.

From the end of 2013 until the autumn of 2018, I regularly wrote short personal/observational pieces that were published in a monthly arts and culture paper, the SouthernMinn Scene, then online for a similarly minded site, The Next Ten Words. Save for the original documents on my laptop from this time period, and the actual physical copies of the SouthernMinn Scene I kept, little if any trace of this era of my output still exists today. Part of the appeal of having a website has been the idea of republishing select pieces—not rewriting or revising. It is humbling to go back and read your own work from a number of years ago, but it is a reminder of both how far you have come in the interim, but also where you were hoping to go, or the voice you were working towards adopting, at the time it was written.

This piece, “Fathering,” was written and published in December 2017, for The Next Ten Words.

My wife is constantly reminding me that some people want to have children, because this is something I commonly lose sight of.

For a number of years now, I’ve been under the impression that nearly all children born are the result of forgotten birth control pills or a torn condom. But no—that’s not the case. There are couples that actively try to conceive a child, and want to bring another life into this world.

I have a difficult time wrapping my head around why anyone would want to do this—to themselves, or to the unsuspecting child they created. No child asks to be born. And there are already entirely too many people in this awful world, so I’m at a loss as to why you would want to make more when the option to not do that is right there.

There have been times when we know a couple who are expecting, and when they’ve announced it, I’ve responded to the news by saying, “So….you guys meant to do that? Congratulations, I guess.”

To me, being a parent seems like an insurmountable amount of work—of, among other things, energy, patience, and money, and I just cannot see myself as someone who has it within them to do that, at least not with another human life. Being a dad to our companion rabbit also requires energy, patience, and money, too, sure—but it’s different. I’ve never claimed that it is the same.

People occasionally suggest to me that I’d be a ‘good father,’ a statement that I’m usually quick to tell them is inaccurate. Half jokingly, I tell people I like buying dumb shit way too much to be a responsible parent. The days of buying expensive vinyl boxed sets would be over because the baby can’t eat 180 gram vinyl reissues, and I’d have a college fund to think about starting, or something.

But really, what I want to tell them is, what have I ever done that makes you think I even want to be a father, let alone, would be a good one?

* * *

In 1971, Golden Books published the title The Monster at The End of This Book. Written by Jon Stone and illustrated by Michael Smollin, the book features the Sesame Street character Grover—the conceit of the book is that Grover is aware there is a monster at the end of the book, and with each page that turns, implores you, the reader, to stop reading, as to avoid getting to the end and finding the monster.

By the end, it is revealed that Grover himself is, in fact, the monster—not a scary one, but a loveable and furry one, claiming he knew this was how it ended all along.

There is a monster at the end of this essay. I want you to know that now.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th—the ‘Feast of The Immaculate Conception,’ a Catholic Holy Day of Obligation. I only know this day exists because I was raised Catholic¹, and I only remember that it’s my father’s birthday because my mother would joke about how he thought he was Jesus.

Almost 20 years ago, I left my father sitting in a Country Kitchen, at a table with empty plates and an unpaid check. I was 16, and doing this was supposed to be some kind of grand, emotionally charged act—telling him that I no longer wanted to continue what little visitation we still had at that point.

It came out all wrong, though. It was rushed—delivered in a nervous jumble after we had finished our meals. It ended with me saying, “And if you don’t mind, now I’m going to go.” I got up from the table, leaving him with a blank, possibly confused look on his face, walking out of the restaurant, never looking back.

Since then, I can count the number of times I’ve seen my father on one hand: my high school graduation, an awkward dinner shortly before I left for college, the first play I was cast in during my sophomore year, and then college graduation.

I have spoken to him on the phone once, slightly over a decade ago, when he called me out of the blue on a Sunday evening to tell me that his mother—my grandmother, I suppose—had passed away.

For many years now, we correspond through irregular emails, with months passing by before the next one arrives.

We are not close.

Keep reading. There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

I don’t understand the mentality of wanting to be a parent—to have that need, or desire. I’m not sure where it comes from. Perhaps people think that’s just what they are supposed to do: go off to school, get a good job, settle down with a spouse, and then begin ‘a family’ in the traditional sense of the word.

The very idea of being a parent, and everything that comes along with it, is an exhausting one when I think about it. I’m not sure where parents find the energy—and there are times when I am certain they aren’t sure where they find that energy either. Whenever I see mothers and fathers out with their children, they seem so tired. Sleep deprived, sure, if the kid is young enough, but it’s more that they seem tired in a world-weary, beaten-down kind of way.

I’m not sure where a parent finds the energy to care—not just for the life they’ve selfishly brought into the world, but about what that kid is going to be interested in and want to talk to them about. Once, at work, I encountered a woman who had a young boy with her. He was clutching onto her mobile phone, not looking where he was walking, and she was trailing behind him. Since it’s in my job description to do so, I asked her if there was anything I could help her find. She took a moment, then said, “No. Not unless you can tell me where the Pokémon are.” There was a look in her eyes—a sadness—that screamed “Please kill me.”

It is a moment like this that makes me feel remorseful for everything I subjected my parents to when I was young—every action figure I told them about, every comic book I explained, every drawing I doodled, and just had to show them. Every stupid movie for kids, I made them suffer through. I’m sure that I tested their patience, and that it took everything they had within them not to say, “Holy shit, kid, I don’t care,” because I’m almost certain that’s what I would say if I were in their position, because I am confident I do not have that kind of compassion and tolerance within.

I can’t fathom this level of patience and energy now, but maybe it just happens when you become a parent to a human child—maybe you unlock all these abilities and all this potential you never knew existed within. Maybe you find yourself becoming a more patient, tolerant, and compassionate person. The kind of person who listens, and instead of feigning interest, is actually interested.

The thing about having a child is that I don’t understand why people think they are so great that they need to create a smaller version of themselves. I’m narcissistic enough to be charming for a few minutes at a time in a social situation; however, I’m not narcissistic enough to think that I am just so amazing that I need to make more of myself. My genetics are very badly damaged, and I can’t see the reason why I’d want to pass that along.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th. This year, he will be 63 years old.

My parents were married in 1974, and I was born in 1983—what those first nine, childfree years were like for them, I do not know. My mother filed for divorce in 1995.

For most of my father’s career, he was an engineer, and even now, I still have no idea what an engineer actually does. When I was very young, he worked for the Thermos Company, which meant that during the 1980s, he brought home a lot of free, plastic lunchboxes with licensed characters on them—like Batman, the ‘real’ Ghostbusters, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Maybe a year or so after my parents divorced, he took a job working for the Ertl toy company, based out of Dyersville, Iowa, the same very small farming community where a bulk of Field of Dreams was filmed. He moved to Dubuque, the closest large city. Within a few years, he moved to Wisconsin—I don’t remember why; then to Indiana for a number of years, and most recently, Tennessee.

He sent out an email within the last month—not just to me, but to a number of people, including his siblings and their children, who, I suppose, are my aunts, uncles, and cousins—family that I haven’t seen or spoken in to in decades—stating he and his second wife had sold their home in Tennessee and were going to be living in a motorhome. “Kind of like tiny home living,” he explains. “Trying to make life a little less complicated.”

We are not close.

* * *

I don’t have a lot of bad or good memories of my father—I’m not sure that I have a lot of solid memories of him at all. Just fragments and moments, the context long forgotten and the edges blurred and faded from time.

I remember the collared shirts, ties, and slacks he would wear to work, promptly changing into an old pair of blue jeans when he came home shortly after 5 p.m, and the way he rarely sat on the couch, but would favor sitting on the floor in front of it, his long legs stretched out and crossed at the ankle, sticking out into the center of the living room.

I remember the overpowering scent of his Speed Stick deodorant when he’d come into my room to say goodbye before he left for work in the morning, and I can recall the thick, revolting smell of the ‘tropical mist’ scented Glade Plug-In air fresheners he used in his extraordinarily small, dumpy apartment—the one he hastily moved into during the divorce. The scent was so strong that it would linger on my clothing and in my hair once I returned to my mother’s apartment following weekend visitation.

I remember short games of baseball and football in the backyard, and basketball in the driveway. I remember his long Sunday morning walks out of the neighborhood, down to the nearest gas station to buy the Sunday Chicago Tribune, and how in the arts section, he read about Liz Phair, Urge Overkill, Veruca Salt, Red Red Meat, and Smashing Pumpkins.

I remember his dirty beige station wagon with its shit brown interior, and how one cold winter morning, when he was driving me to school, smoke started to billow out from somewhere in the dashboard.

I remember the sparkling waters he always drank, and how, when I had a La Croix for the first time as an ‘adult’ in college, before I took a sip of it, I thought, “I can’t believe I’m drinking this.”

I remember that, when I was around 10, he was tasked with giving me ‘the talk.’ But we had cable when I was a kid, and I had friends who had older brothers, so there wasn’t much of it that was new information to me.

I remember waking up one August morning in 1994 to a closed bedroom door, hearing my parents having a very tense discussion in the other room. I listened for a very long time, trying to make sense of what I heard—I couldn’t figure out if they were having a discussion about somebody else, or if they were having an argument. I stayed in bed for what felt like an eternity, and waited through an extended period of silence before getting out of bed and pretending I had just woken up.

I wrestled with this for months before I finally said something to my mother about overhearing them, as in her old, gray Pontiac hatchback, in the parking lot of a K-Mart.

There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

Becoming a parent—I mean, choosing to bring another life into this world—is a huge investment, and the payoff in the end isn’t guaranteed. It’s not promised that, despite all your efforts, everything is going to turn out for the best. There is the risk of birth defects or developmental disabilities; the threat of passing along your debilitating depression and anxieties, or other, more severe mental illnesses. There is the possibility that, even if you give them everything, and you try your hardest, they will still turn out to be an ungrateful little shit, and you’ll spend your days agonizing over where you went wrong.

There are moments when I can see how taxing it is emotionally to be a parent. It puts you on edge constantly, and anything, no matter how small or insignificant, could be the thing that sets you off. I watched a teenage girl bump into a case in a bookstore; the force of her movement knocked a book that was on display over, sending it to the ground. Without any warning, the girl’s mother spins around and, in a harsh whisper, hissed, “WHAT IS THE MATTER WITH YOU?” to her stunned daughter.

I watch the easily agitated father of two young children. In the grocery store, he holds a plastic produce bag open, commanding one of his children to take the cabbage from the shelf and place it in the bag. The child isn’t listening at all; in fact, the child is toddling in the opposite direction of this man, who suddenly barks, “Are you going to come over here and do this or not?”

I watch the young, conservative couple, lugging around one child who can’t be more than two, with a newborn now in tow—the man and woman who cannot be out of their early 20s, argue with one another as they shop; if they aren’t arguing, they trudge in silence, looking absolutely miserable, as the older of their children speaks incessantly to no one in particular.

* * *

My father remarried in 1997—either the day before, or the day after Valentine’s Day. It was a courthouse thing, and for some reason, I didn’t think it would last. But they are still together, now living in a mobile home to make things ‘less complicated.’

My father’s wife is the first person I ever heard use the word ‘nigger.’ I was young—probably 13, so I had obviously heard it used in rap music, but I had never heard another person that I knew use it. We were eating lunch—the three of us—and I said something about wanting to see the Martin Lawrence and Will Smith movie Bad Boys. My father’s wife, without so much as batting an eyelash, turned to me and told me she didn’t want to watch any of ‘those nigger movies.’

One of the first times I interacted with my father’s second wife, the three of us were going out to dinner. It was a Mexican restaurant, and I had ordered a bean burrito. After we placed our orders, she exclaimed in a loud and jovial voice ‘Beans make ya fart!’ I was mortified, and never really sure why she said this to me—was it some kind of forced effort on her part to try and identify with the teenage son of the man that she was involved with, or was she really just this crass?

* * *

When my wife and I were getting married, I had made it clear that we were not going to invite my father to the wedding. There may have been a small moment of deliberation on my part because the decision was one of minor contention for my soon-to-be in-laws, specifically my mother-in-law, who had a difficult time wrapping her head around why I didn’t want him there, and was certain I would regret not including him.

Others supported my choice, but I had been warned that there would be a time when I would have to tell him that I had gotten married, and that we had purposefully chosen not to invite him. That time arrived a little sooner than I was anticipating—maybe a month later.

He had sent one of his ‘Hey, how are you doing’ emails, and I’m not even certain why I was so moved, at this point, to confess—if anything, I should have waited until I had a better grasp on how I’d handle it, because I certainly was not prepared for his response.

There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

For 15 years, I resented my father. I was aware of how emotionally abusive he had been to my mother before they separated. He was cold and distant, and as a child, shuffled off to his apartment every other weekend, I felt like he wasn’t trying very hard. I blamed him for the distance that had grown between us.

I thought that he was the monster.

To my surprise, he had been carrying around resentment for 15 years as well—but toward me. He felt like I had never been trying very hard, and he blamed me for the distance between us.

I was the monster.

I was the ungrateful little shit, and my father had spent his days agonizing over where he had gone wrong.

This was all revealed to me over a series of lengthy, accusatory emails that were sent after I told him I had gotten married and we had intentionally not included him. He was hurt by my decision—a feeling I truthfully had never thought he was capable of, but he was. At one point, his wife wrote back to me, implying she was reaching out to be unbeknownst to him—though they are the kind of couple that shares an email address, made up of their initials and a bunch of numbers.

During our exchanges he told me that if I really wanted to work things out, it wouldn’t be through email—it’d have to be over the phone. We’d have to have a real conversation about where things were, and how to move past it. It was either that, or things could stay the way that they were—strained and unresolved.

At the time, I didn’t have it in me to pick up the phone and have that kind of a conversation with my father, because I didn’t know what to say. I still don’t—I don’t have it in me; I don’t know what I would say. Things are still strained and unresolved. That was my choice, and I cannot imagine where I’d find the interest in repairing things.

We are not close.

There is a monster at the end of this.

* * *

It turns out I have two slightly more solid memories of my father—one of them is good, the other is not.

When I was probably eight years old, my father took me sledding. Growing up, there had been an unsanctioned sledding hill next to a Wendy’s, but someone had gotten hurt pretty badly, and the property was pretty much off-limits after that. Instead, we went to one of the city’s parks. I remember it was crowded, and difficult to find a space of your own to use as you glided down the hillside.

I was going down the hill, and I must have lost control of what I was doing, and I crashed right into a large, frozen bale of hay. The way I remember it, I may have been briefly knocked out from the impact; I can recall coming to, and just losing it completely—screaming, crying, terrified. I am certain it was an unsettling sight to witness for everybody else. My father ran down the hill, scooped me up, and took me back to his car, driving me back home as I tried to calm myself down.

It was a Saturday night, and my parents had rented the movie Tombstone. I was 11 years old, and this was shortly after the conversation with my mother, in her car, in the parking lot of a K-Mart.

I was in my room, with the door closed, trying to watch television—but I couldn’t hear it because the movie my parents were watching in the living room was too loud. Loud like my ear was pressed up against the speaker and the volume was up as high as it could go.

For a while, I wasn’t sure what to do, but after straining to hear the shows I was watching on Nickelodeon, I opened my door and wandered down the short hallway into the darkness of the living room. “Would you be able to turn down the TV, please?” I quietly asked.

My father turned his head very slowly, took a moment, and then responded, “Only if you turn down yours.” Then he went back to watching Tombstone.

I can remember that I wasn’t really sure how to respond, so I turned around and went back into my room. A few moments later, my mother came in to check on me and apologize. She said she had no idea my television was even on; she thought I had been asleep.

There is a monster at the end.

* * *

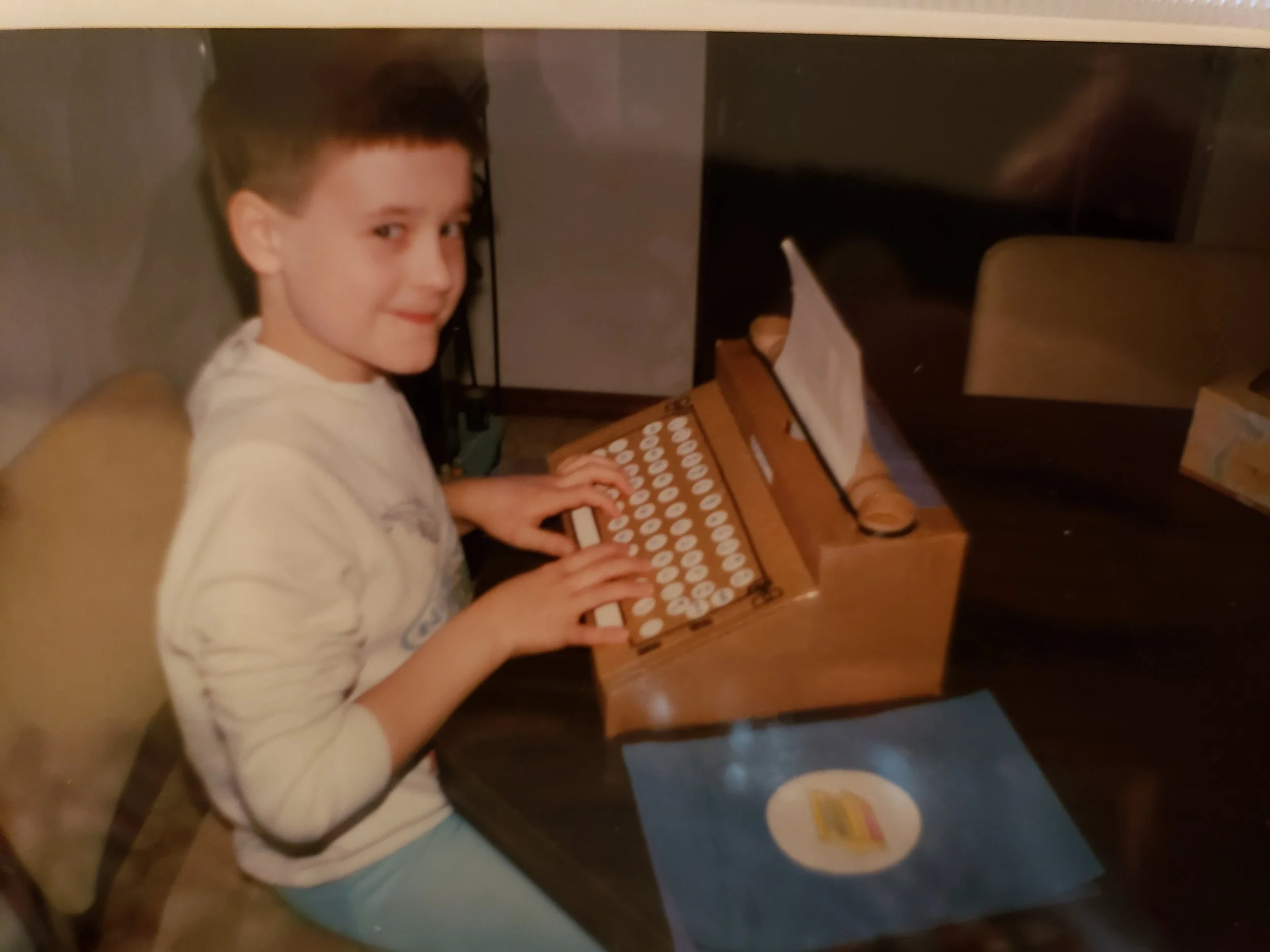

When I was in my final year of college, I was in a writing class, and one of our assignments was to take an old family photograph and write something based around it. The assignment was given to us shortly before a holiday break—our professor presumed many of us would be traveling back home and would have access to these kinds of artifacts.

The photograph I used was of me and my father at a pumpkin patch—I’m probably around seven years old, wearing a Darkwing Duck fanny pack; my father, stuffed into his old, thick, faded denim jacket. As part of the assignment, we were to bring the photos in for the rest of the class to look at. So many of the other students were quick to comment on how much I looked like him.

Occasionally, I see it—I’ll catch a glimpse of myself and I’ll see it in my small, sad-looking eyes, or when I run my hand over the top of my bald head. I didn’t make it out of my 20s with a full head of hair—my father at least made it into his late 30s before it really started thinning.

I’ll think about it when I realize that I, too, favor sitting on the floor, legs out stretched and crossed at the ankle, rather than sitting on the couch.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th. Some years, I neglect to send him a ‘Happy Birthday’ email. This year, I remembered.

There are times when I forget about my father entirely; there are times when I wonder if I will ever see him again. There are times when I wonder if we were to pass one another on the street, would I recognize him? Would he recognize me?

There are times when I say that I am too irresponsible to be a parent, or that I would be a horrible father—my wife is always very quick to dispel this. She tells me that I would be good, and that I only think these things because of how badly things turned out with my own father.

She tells me that I wouldn’t be like him.

I would like to believe that, but there are moments when I am not entirely sure.

We’ve reached the end.

And, there is a monster.

1-The really great thing about Catholicism is that it’s almost entirely based around fear and guilt. So that, even as an adult, when you’ve come to the conclusion that there is no god and organized religions are a joke, if you were raised Catholic, you are still, despite your best efforts, unable to shake the feelings of guilt and fear that accompany nearly everything you do.

An Irresponsible Journalist

Reflecting on the tenth anniversary of a few weeks spent in hell with a right wing extremist conspiracy theorist.

I wonder if Alan remembers me at all, the few times that I have seen him around town—if he remembers my face. Or if he has forgotten completely.

He had read a poem, a long time ago, at a literary event we were both participating in—he had, maybe, read more than one, but the one I remember the most was a charming, satirical ode to the pen he had just asked his wife for, that he would certainly misplace almost immediately after it had been handed to him.

He and his wife were my neighbors for a while—maybe for a year or so. We didn’t know them, really. Not even after he and I both read pieces at the same event. Alan and his wife—her name is Heidi—before they had their children, or at least before they had more than one, lived two houses down from the home my wife and I were renting.

Maybe just a friendly wave, or a hello. Between myself and Alan, and Heidi. Nothing more.

Alan did not remember me, I do not think, when I knocked on the door of his office in January 2015.

He did not remember my face, from two houses down. Or from the literary event.

I knew he was inside, but he refused to answer. I knocked. I waited. No response. I slid my business card—it said “reporter” on it, as my title, underneath, and then began to walk away. I had made it back outside into the cold air when I heard him behind me, standing in the doorway to the building where his office was. He wouldn’t come any closer. He was hesitant. There had been threats against him, and his family. I asked him if he wished to comment, or make a statement, or be interviewed.

I’d like to believe he told me he’d think about it, but I can’t, with confidence, say that was his response to me. He never reached out, regardless, and I didn’t want to press him anymore after that.

It didn’t seem worth it.

I wonder if he remembers me at all, as the years have passed and in the times I have seen him, or his wife—always smiling with a mouth full of bright, white teeth, around town. Their children, so much older now.

I searched his name online, and one of the first things that came up was an opinion piece that he had contributed in December 2023 to the local newspaper that, roughly ten years prior, had employed me, and pushed me into this story that he was, unfortunately, adjacent to. The local newspaper that had asked me to trudge down the street from my cubicle in the newsroom to his office and knock on his door to ask for a comment, or if he wished to be interviewed.

The opinion piece he had written was titled, “Reflections of An American Jewish Zionist.” The paywall prevents me from reading any of it.

I don’t think I wish to know what it says, though.

I wonder if he remembers me at all.

*

Usually once a year, sometimes more than once a year depending on how petty I might be feeling about it, I will look to see if James Fetzer has died yet, or not. As of right now, August 2024, he is still alive—he’s 83.

On the page with the search results, Fetzer’s Wikipedia is the first thing that comes up, and at the top of the page, there is a photograph of him, credited to Rolling Stone.

Fetzer is in a courtroom. He’s wearing a maroon button-down shirt and a gray blazer. His hair is bright white and thinning. It’s parted on the right. He looks smug, in the photo. He’s looking over his shoulder. But he also looks concerned. Concerned and maybe a little disappointed.

The photo is from a short Rolling Stone piece written by EJ Dickson, published in 2019—“Sandy Hook Father Awarded $450,000 In Conspiracy Theorist Suit.” Among other published works, James Fetzer is responsible for writing a 450-page book entitled Nobody Died At Sandy Hook.

He was sued for defamation over his egregious claims that the 2012 elementary school shooting never happened.

He lost.

*

I was already in way over my head with the job in January, 2015.

Or, if not in over my head, I realized that, a mere four months in, that I was not cut out for the more unsavory aspects of the job that I was being asked to do—things that I had not given consideration to when I had applied. When I had interviewed. When I had accepted. When I showed up on my first day, eager, excited, nervous.

Or, if I was not in over my head, I was just simply not cut out for the stress. Not at all built for the anxiety that came with the line of work.

Not at all built for the ambulance chasing I had been, and would be, asked to do—grim invasions of privacy in somebody else’s vulnerable moments that I would just never become comfortable with.

I didn’t have the patience, or the enthusiasm, to chase after every lead, and write every story. By the end of my time as a news writer, any patience, or enthusiasm that I had for any story, regardless of what it was about, was gone completely.

And no point, during my time employed by the newspaper, did I have the patience or the enthusiasm that was necessary to understanding all the pieces when it came to stories that were not even nuanced, really, but were merely overcomplicated by their many layers.

Stories that were overcomplicated, like James Fetzer.

I had no background in journalism. I was not familiar with AP Style—my first slip-up of including an Oxford comma where one should not have been in one of my earliest articles sent my editor into an absolute tizzy.

I can still hear him. Jerry. His southern Illinois drawl, shouting, somewhat in jest, but also somewhat in earnest, at me, across the rows of cubicles in the newsroom, exclaiming that from just a single instance of the Oxford comma in a news story, he was going to have a problem with me, and trying to break my habit of using it.

I had no background in journalism. But I could write. And, at that point, I had been a resident of Northfield, Minnesota, for around eight years, and had already worked myriad different jobs, so I was connected, or at least somewhat known, within the community, which is something that others in the newsroom, who were much younger and fresh out of “J School,” as it was often called, and had relocated to Northfield, for the job, could not offer.

I had no background in journalism, but was hired, nevertheless, as a reporter, for the Northfield News.

I lasted two years, nearly to the day, which is about a year longer than a lot of other reporters would last in this specific newsroom, for whatever reason. Whether they, too, realize they are not cut out for it, or they move on to write for a different paper.

I lasted two years, but I was already in way over my head, or simply not cut out for the more unsavory aspects of the job, merely four months in.

*

I’d never heard the name James Fetzer prior to January 2015, and I would like to think that if the events that occurred over the course of roughly a month, or, like, a month and a half, had not happened, or had even just unfolded a little differently—I would like to think I would have never heard his name.

I would like to think that this wouldn’t have been an experience in which I had the utter misfortune of being involved, adjacently or otherwise. That this wouldn’t be a story that I, rarely, if ever, wish to recount to any degree, but a story that I still carry with me.

James Fetzer, then, wouldn’t be someone that, at least once a year and sometimes more than once a year, depending on how I am feeling, I look up online to see if there is an obituary and if the tense of his Wikipedia entry has been altered from present to past.

I'm hesitant to say this all started with a tip. But it did. At least my introduction to the overcomplicated nature of these events. I was gently pointed in the direction of something that had already quickly developed, and had immediately gotten out of control.

I was encouraged to pursue it as a story.

I have heard the name James Fetzer. You cannot unhear it.

I first heard it in January of 2015. The middle of what became a long, frighteningly cold, and in the end, an unforgiving winter. A winter that would, eventually, take more and more of me.

This started with a tip. And that is ultimately how a lot of stories at the newspaper begin. Gently pointed in a direction. Given a suggestion. Encouraged. People, in the community, would reach out. They felt compelled to do so. People, in the community, often thought their stories were worth sharing with a larger audience. A mother would contact the newspaper, and implore someone in the newsroom to write a piece about her daughter—a plucky, young Girl Scout, driven to sell the most boxes of cookies for her troop.

People in the community would reach out. The elderly gentleman involved in an area vocal group would continue to leave information at the front desk of the newsroom about upcoming performances, with the hope that the paper would turn it into a feature story—only to become disappointed and angry when it was not deemed worthy of a story, feature, or otherwise.

People, in the community, thought their stories were the most important.

I had been given a tip. Or given a suggestion. Encouraged. Pointed in a direction. An acquaintance had sent a message to me, directly, informing me of what had already transpired, and was quickly escalating, between Fetzer, a handful of his supporters, and members of the community.

The truth, though, is that regardless of whether I had been given the tip or not about what was happening and what was on the cusp of happening involving James Fetzer, someone in the newsroom would have eventually had to deal with it. Whether that someone would have been me, or not, I can’t be certain.

I often was, the longer I stayed at the job, just a warm body in the newsroom at the wrong time when someone, from the community, came in, asking to speak with a reporter.

Their stories, of course, were the most important.

*

James Fetzer retired from his position as a professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth in 2006—I made the mistake, in the first story I had written about him, and the controversy he brought with him to our small Minnesota town, of simply referring to him as a retired professor.

He was quick to reach out, via telephone, and chide me. He had earned the title, Distinguished McKnight University Professor Emeritus, and I was to describe him as such.

Fetzer was always quick to reach out, via telephone, and chide me about the small details of my news stories about him that he did not like. His number becoming the first of many to end up on a piece of paper, taped to my desk, by the telephone, on a “Do Not Answer” list.

Fetzer was born and raised in California before studying philosophy at Princeton, followed by a stint in the Marines, stationed in Japan, during the 1960s. He became an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky in the early 1970s, but was denied tenure—there is a part of me that is curious as to why, but there is a part of me that can take a guess as to why—and spent the next ten years in visiting professor positions throughout the country before settling into his role in Duluth, in 1987, where he remained for nearly 20 years.

Of the information about James Fetzer, offered by his Wikipedia entry, it is not specified when, exactly, but there came a point in his life when he became interested in the promotion of conspiracy theories—the list is long, and it grows increasingly more unhinged and honestly rather sickening, the more you read up on what he believes, and the hurtful misinformation he has spent a large portion of his life spreading.

It can be difficult, honestly, to know where to begin—Fetzer believes, among other things, that John F. Kennedy’s assassination was planned by this country’s own government, and that the short, silent film clip of Kennedy in the motorcade, captured by Abraham Zapruder, is “fake.”

Fetzer believes that Minnesota United States Senator Paul Wellstone, who died in a plane crash in 2002, was actually killed as part of a plan orchestrated by Karl Rove, as well as other “out of control” Republicans.

Fetzer believes that the Holocaust is “not only untrue,” he is quoted as saying, “but provably false and not remotely scientifically sustainable.”

He believes that the 9/11 attacks were, like Kennedy’s assassination, perpetrated by the United States government, and that the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings was the work of controlled demolition.

He believes that nearly every very public and tragic event in over the last decade simply did not occur, and that they are often staged or are training exercises—events like the Boston Marathon bombing, or the shooting in Parkland, Florida, and at Pulse Nightclub.

He believes, among other things, that “Nobody Died At Sandy Hook,” and that the elementary school shooting that took place at the end of 2012 didn’t actually take place at all—that it never happened and it was a “FEMA drill.”

He believes, and has stated more than once, that funerals can be staged and death certificates can be forged.

He was so emphatic about these beliefs that he was willing to defend them, in court, when he was sued for defamation, by one of the parents of a student who died in the Sandy Hook shooting.

He lost.

*

In my mind, I always think that Norman looks a little like Phil Collins. But I realize that is maybe not really the case, and maybe I only think that because they are both short, white men of a certain age. And also both British.

I never liked Norman. I still don’t. And when I inevitably have to interview him, for the central role he played in what brought Northfield, Minnesota to the attention of James Fetzer, Norman tells me that he has always been a fan of “alternate truths.”

Conspiracy theories.

I never liked Norman. I sometimes used to try and see why people did. Maybe nobody actually did, and they only tolerated him. I am sure he thought himself charming, or charismatic enough, and that he could coast on that.

I had always been suspicious of him.

Norman, for a number of years, prior to this, saw himself as a restaurateur in the community. He had some success owning a dumpy pub—it always smelled damp, and like stale popcorn, but it was popular with certain circles of people who enjoyed what he had said to me once, in conversation, was “pub culture.” He also had some success owning an Indian restaurant—the quality of the food, often hit or miss, but it, like his pub, was inexplicably popular within certain circles of people in a small town flanked by two liberal arts colleges.

Norman got well in over his head, financially and just in terms of sheer responsibility, when he tried to open two additional restaurants, as well as a commercial kitchen space available to rent. The other two restaurants floundered, off and on, for about two years, while he tried to revamp the menus regularly at each, before they both unceremoniously shuttered.

I never liked Norman, and by the end of all of this, I liked him even less.

*

I didn’t have the patience, or the enthusiasm, to chase after every lead, and write every story. I certainly did not have the patience or the enthusiasm that was necessary to understanding all the pieces when it came to stories that were not even nuanced, really, but were merely overcomplicated by their many layers.

I had been given a tip. I have told you as much, already.

An acquaintance felt compelled to share with me, directly, information about what had already transpired. Things were already out of control—it happened quickly. And there were, of course, ways for it to be contained. Different decisions that could have been made to prevent things from getting any worse.

As a fan of what he called “alternative truths,” Norman was aware of James Fetzer, and his beliefs, and apparently was fond of them. Saw some kind of value in them. He was curating a series of “talks” as he described them, at his pub, where two people, on opposing sides of an issue, were expected to debate. The talks were supposed to be lively, but friendly, in the end. And as a fan of these alternative truths, Norman had extended an invitation to James Fetzer, and asked him to participate in one of these talks.

Fetzer accepted.

And in his acceptance of the invitation, if I am recalling this correctly, his name began to appear on the pub’s event calendar, as a means of promotion. The mostly liberal clientele who at the time, favored Norman’s pub, saw Fetzer’s name and knew enough about him, and his beliefs, that the backlash, and the uproar, started immediately.

The person who had apparently been slated to debate Fetzer—Alan. Alan, who would not answer the door to his office when I knocked on it. Alan quickly removed himself from the debate and then began circulating a petition as a means of protesting Fetzer’s scheduled appearance.

Norman was besieged with angry phone calls and messages—angry, but also disappointed, presumably, and frustrated—from patrons of his pub, and the community at large.

There’s a fine line, in news writing, or “reporting,” between subjectivity and objectivity.

It took me a long time, and I don’t think that even in the end, I was very good at it, because I often struggled to err on the side of objective writing in the stories I was responsible for. It was hard for me—it still is hard for me—to remove myself completely from the things that I write.

It seems like I should have written more, and maybe it seems that way because they were difficult stories to write, and arduous interviews to conduct, but I wrote three stories chronicling James Fetzer’s experience in Northfield, Minnesota, and in the earliest of the three, where the stage was initially set and we are introduced to some of the players involved, it was very hard to remain objective.

Almost impossible.

Certainly difficult when it came to simply just reporting the opposition here—Fetzer’s beliefs, and everyone who disagreed with them, but the more I sat with this story, as it was unfolding, it was a challenge for me not to interject, or editorialize within the moment.

I was never certain if I could interject. If it was allowed. Or discouraged. I think, if anything, specifically in a situation like this one, my hope is that during the conversation, the person I was interviewing would arrive at a realization, or a truth, that was more obvious to me than it perhaps was to them.

Or maybe they were aware, and just unwilling to divulge it, as a means of avoiding the acceptance of being in the wrong.

Rather than addressing the concerns of his patrons and the larger community directly or even realizing the mistake he had made, and canceling the event as a means of keeping the peace, Norman passed along every message he received—many of them emails—directly to Fetzer.

And Norman, allegedly, at the time I interviewed him, a decade ago, did not see why this might create a much larger problem.

He, quite literally, thought nothing of it.

*

And upon receiving the messages from concerned and upset members of the community that Norman had forwarded along, James Fetzer could have gracefully accepted that his harmful rhetoric was not welcome in Northfield, and faded away back into the extremist cesspool he crawled out of.

But that is not what he did.

It isn’t funny, really. Maybe funny in an appropriate bleak way. But if you search the name “Veterans Today” online, the website itself is not the first result, but rather, it is a Wikipedia entry, which describes it as an “antisemitic and conspiracy theory” site, as well as a “pro-Kremlin propaganda outlet.”

Veterans Today, though, alleges it is a “military veterans and foreign affairs journal.”

In 2015, Fetzer was a regular contributor to Veterans Today, and in response to the pushback he had received about his scheduled appearance in Northfield, for a debate at Norman’s pub, he published an essay called “The Abdication of Reason and Rationality in Northfield, MN.” In it, he laments about the outcry he was on the receiving end of, and defends his right to spread his harmful, dangerous beliefs and rhetoric.

And if Norman allegedly saw nothing wrong with sending these messages directly and providing Fetzer with the contact information and full names of the individuals who were upset, angry, and frustrated, Fetzer himself allegedly saw nothing wrong with including screenshots of these messages in his piece for Veterans Today.

He saw nothing wrong with not obscuring or censoring the contact information and full names of the individuals who were upset, angry, and frustrated in those screenshots.

He told me that he, in fact, had no idea how to obscure, or censor, this information. No knowledge of how even a rudimentary program on a computer might be able to help him do this.

The threats, I think, started almost immediately.

Hate mail. Whatever you wish to call it.

The threats came from the readers of Veterans Today. Threats so vile and serious that a person like Alan—Alan, who had written an ode to the pen he had borrowed from his wife and would certainly misplace almost immediately. Alan, who would not answer the door to his office when I knocked on it, on a cold January afternoon.

Threats so vile and serious that, apparently, the FBI became involved.

It was after Fetzer’s piece on Veterans Today was published when I had received the tip.

*

I never liked Norman. He was aloof and smug—he had been, with how he ran his businesses and ran two of them right into the ground. And he was in the conversation I had to have with him, after things had immediately gotten out of control.

Norman, in the interview we had, used, I’m sure, what he thought was the most clever line he could think of at the top of the conversation. “I didn’t expect the sort of Spanish Inquisition,” he said, laughing at his own joke.

He used the same line in the conversation he had with Jon Tevlin, a writer for the Star Tribune, based out of Minneapolis, who had also picked up the story. And adding to the stress I was under, simply trying to unpack the details of something so overcomplicated, my editor, and his boss, the publisher of the paper, were quite literally breathing down my neck for a story, because they did not want to get scooped, in our own town, by a much larger publication with more available resources.

Tevlin was a much more capable writer than I was ever going to be. He left the Star Tribune in 2018, but he had well over a decade’s worth of experience, and he was a columnist too—less focused, in his piece about Fetzer, on objectivity.

I had been on the job for a little over four months.

*

Things continued moving at a pace I could barely keep up with. Even until the end, I always felt like I was a few steps behind where I was expected to be. And after the first of the three stories I had written about James Fetzer was published, things only got worse for everyone involved.

I am uncertain what writing for a newspaper is like today. But, in 2015, writing for a newspaper meant you wrote for both the publication that went to print and for the web, which is where a large portion of the readership came from. It was also, at this time in the history of the Northfield News, an absolute nightmare to moderate the comments posted from registered users of the site, regarding certain stories.

The website has been subject to a number of redesigns and relaunches in the last ten years. The first attempt, prior to my departure from the newsroom, made it so that users had to log in with their Facebook credentials in order to comment on a story. Prior to this, though, anyone could register with the site and create a somewhat anonymous account—revealing as much or as little of their identity as they wished to.

The comments on all of the stories involving Fetzer became a shouting match for a handful of specific people from the community, trying to take one another to task over the whole ordeal—as well as Fetzer himself, and a few of his supporters from Veterans Today, chiming in, making things more insufferable and caustic.

Things continued moving with a pace I could barely keep up with, but shortly after the first story about all of this was published, Norman finally made the decision to call his politically charged “talks” at his pub off completely—the event series was scrapped.

“Our livelihood is threatened. Our Staff is harassed. Our regulars worried,” Norman said in the statement, announcing that he was canceling the “talks.”

And this could have been the end, honestly. It could have. After being met with the initial criticism and outcry, and after the event itself was canceled, James Fetzer could have made a sensible decision. And chose to bring his harmful and dangerous beliefs elsewhere.

Fetzer chose to do something else.

And this is a moment when, in this story, as it was unfolding, I wish I had done something differently.

If I had perhaps been stronger emotionally, or more confident, that I would have asked different questions. If I would have had it within to interject, and point at what was obvious to me. Because there were things that bothered me, of course. And questions I felt like I should have, or could have asked, but was too afraid to open my mouth.

That is what I always come back to, truthfully, when I think about this story. I think about James Fetzer, yes. I think about the hateful things he said, and the looming sense of dread that cast a shadow over my workday for around a month. But I think about where I fell short—ethically, for myself. And the shame I still carry with me—about what I should have, or could have, done differently.

I didn’t believe Norman, when he told me that he didn’t think anything would happen when he passed along the personal contact information, and full names, of the people in the community who were angry with him, and his decision, to invite a Holocaust denier and conspiracy theorist to speak at his pub.

I didn’t believe James Fetzer, when he told me that he didn’t think the readers of Veterans Today would go after those same people, when he shared the personal contact information and full names, of those who were upset, and disagreed with his beliefs.

I continued to disbelieve Fetzer, after the events were canceled, and he refused to go away.

*

James Fetzer is not a reasonable man.

It’s something I was aware of, and understood, even before I spoke with him on the phone while I was putting together the first story about him, and the violence he attracted. And because Fetzer is not a reasonable man, at all, he refused to be silenced.

It is announced, after Norman canceled all of his politically leaning events at his pub, that Fetzer will descend upon our small, Minnesota town, regardless.

In late January, we, in the newsroom at the Northfield News, received word that James Fetzer was going to be speaking in a cramped conference room at the Northfield Public Library the following month.

An associate of Fetzer’s, who also, at the time, contributed regularly to Veterans Today, had a very, very loose (from what I could tell) connection to a Madison, Wisconsin, non-profit, and this individual used that guise to book the space, conveniently neglecting to mention James Fetzer at all in making the reservation.

The staff at the library, as I discovered when I reached out to them for comment, had no idea what was going on.

They were mortified. They were furious. Rightfully so.

In speaking with Fetzer, again, for this specific story, he alleged his friend made the reservation, through the non-profit connection, so that it would be free of charge.

I didn’t believe James Fetzer.

Why should I. Why would I.

I didn’t believe that he had done this intentionally so that he could try to sneak his way in.

I was in no position, emotionally, to counterargue or interject. I remained quiet.

I think about where I fell short—ethically, for myself. What I should have, or could have, done differently.

*

I remember, in the days leading up to James Fetzer’s event at the library—mid-February, Jerry, my editor, was remiss, at first, to even give it coverage, which I was grateful for.

“We’ve given Fetzer a lot of free ink,” he said, his drawl a little weary. However, Jerry quickly changed his mind—regardless of the amount of free ink the paper had given Fetzer, and the controversy surrounding him, it was decided that someone, apparently, needed to be at this event.

“In case something happened,” Jerry said to me, when I was standing in his office.

He didn’t ask me, directly. It was implied. That I had to. I had to be the one. Was there any other way?

So I said yes. Sure. Fuck it. I would go.

I got an “atta boy” from Jerry—one of many that I did receive, from him—his way of encouraging me, I think, during the time he was my editor.

But, an “atta boy,” no matter how many times you are the recipient of one, or a hearty slap on the shoulder—none of that makes up for how much of myself I lost, sitting at my desk, in a cubicle, in the newsroom, for two years.

Seeing James Fetzer, in person, was revolting, and I made no effort to introduce myself to him, either before or after the event.

I hadn’t arrived late enough to have missed any of his presentation—a bland PowerPoint that he could barely get up and running with the equipment he had—but I arrived too close to the beginning of his talk, and I was not able to get a seat.

To my surprise, all of the chairs in the room had been spoken for, with latecomers awkwardly attempting to find a place to stand.

I hoisted myself up onto a ledge near the back of the room, balancing my computer on my lap—it was part of my job, as a news writer, to both take notes, yes, on what I was witnessing, but also, when covering an event, I was expected to share my observations in a stream of 140 characters or less, through the Twitter account I used specifically for this job.

As I sat, I wondered if any of the personalities that lurked within the comment section on the paper’s website, in stories about Fetzer, or other more controversial issues in the community, were in the audience.

I wondered if any of those individuals would, somehow, slip, and reveal themselves, even in passing, before the night was over. If I would be able to put a face to the usernames that became the bane of existence within the newsroom.

Fetzer’s presentation was split between what had been at this time, his two favorite subjects—the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, and the bombing at the Boston Marathon. He was unrelenting, as he spoke, nearly uninterrupted for 60 minutes, barking and yelling one absolutely unhinged, unbelievable, deplorable statement after another.

The shooting at Sandy Hook, of course, did not happen. A hoax. Crisis actors were used. Funerals were staged. Death certificates were forged.

The bombing at the Boston Marathon, also, of course, did not happen. It was an elaborate ploy by the government to, apparently, restrict the Second Amendment rights of American citizens.

After his PowerPoint had concluded, he had time to take a few questions from the audience—I can recall a very frail woman standing up, her voice shaky, saying that she was willing to indulge a number of his beliefs as described that evening, but she drew the line at his statements about the Holocaust.

To this, Fetzer began to fumble, slightly, with how he answered—refusing to actually say he was a Holocaust denier, but again reiterating that he did not consider it to be “remotely scientifically sustainable.”

There was a notoriously cantankerous, opinionated member of the community who was amongst those in the audience—Victor. He would have been in his 80s at the time. He was visibly nonplussed by the presentation—by Fetzer, as a whole, and he spoke up, at the end, and rather than asking a question, simply said the evidence presented was “not very compelling.”

This was, as you might imagine, upsetting to James Fetzer, who snapped back viciously, as did a member of the audience, and apparent supporter of Fetzer’s beliefs and work.

My editor had sent me there, to cover the event, “in case something happened.” And this moment of volatility was what he was looking for. What he wanted.

Nothing did happen, though. Outside of this brief flash of tempers, and raised voices. The moment passes. And the event itself ends rather abruptly—the time for questions or comments from the audience is cut short as library staff, their patience seemingly exhausted, come into the room, announce that the time is up, and ask everyone to leave.

And there are a few places, in these events, as they continued to unfold, where I am ultimately disappointed in myself. I have regrets. And I wish I had done something differently, if I felt like I could have interjected in any way. And parked on the ledge at the back of the conference room at the library, my legs nervously dangling and my fingers furiously tapping away at my laptop, attempting to document what I was witnessing, I didn’t feel like I could truly speak up.

What plagued me, in the end, as we were hastily asked to leave the conference room—bodies spilling out of the narrow library hallway, into the frigid night, and what I think about now when I revisit these events is simply, why are we to believe James Fetzer?

He claims that there are elements to the Holocaust that are not scientifically sustainable, and that those elements are untrue. Why should we believe him. He wasn’t there. He was not living in a Nazi-occupied part of Europe in the 1930s and 1940s.