From The Archives: Fathering (or, There’s A Monster at The End of This Essay)

From the end of 2013 until the autumn of 2018, I regularly wrote short personal/observational pieces that were published in a monthly arts and culture paper, the SouthernMinn Scene, then online for a similarly minded site, The Next Ten Words. Save for the original documents on my laptop from this time period, and the actual physical copies of the SouthernMinn Scene I kept, little if any trace of this era of my output still exists today. Part of the appeal of having a website has been the idea of republishing select pieces—not rewriting or revising. It is humbling to go back and read your own work from a number of years ago, but it is a reminder of both how far you have come in the interim, but also where you were hoping to go, or the voice you were working towards adopting, at the time it was written.

This piece, “Fathering,” was written and published in December 2017, for The Next Ten Words.

My wife is constantly reminding me that some people want to have children, because this is something I commonly lose sight of.

For a number of years now, I’ve been under the impression that nearly all children born are the result of forgotten birth control pills or a torn condom. But no—that’s not the case. There are couples that actively try to conceive a child, and want to bring another life into this world.

I have a difficult time wrapping my head around why anyone would want to do this—to themselves, or to the unsuspecting child they created. No child asks to be born. And there are already entirely too many people in this awful world, so I’m at a loss as to why you would want to make more when the option to not do that is right there.

There have been times when we know a couple who are expecting, and when they’ve announced it, I’ve responded to the news by saying, “So….you guys meant to do that? Congratulations, I guess.”

To me, being a parent seems like an insurmountable amount of work—of, among other things, energy, patience, and money, and I just cannot see myself as someone who has it within them to do that, at least not with another human life. Being a dad to our companion rabbit also requires energy, patience, and money, too, sure—but it’s different. I’ve never claimed that it is the same.

People occasionally suggest to me that I’d be a ‘good father,’ a statement that I’m usually quick to tell them is inaccurate. Half jokingly, I tell people I like buying dumb shit way too much to be a responsible parent. The days of buying expensive vinyl boxed sets would be over because the baby can’t eat 180 gram vinyl reissues, and I’d have a college fund to think about starting, or something.

But really, what I want to tell them is, what have I ever done that makes you think I even want to be a father, let alone, would be a good one?

* * *

In 1971, Golden Books published the title The Monster at The End of This Book. Written by Jon Stone and illustrated by Michael Smollin, the book features the Sesame Street character Grover—the conceit of the book is that Grover is aware there is a monster at the end of the book, and with each page that turns, implores you, the reader, to stop reading, as to avoid getting to the end and finding the monster.

By the end, it is revealed that Grover himself is, in fact, the monster—not a scary one, but a loveable and furry one, claiming he knew this was how it ended all along.

There is a monster at the end of this essay. I want you to know that now.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th—the ‘Feast of The Immaculate Conception,’ a Catholic Holy Day of Obligation. I only know this day exists because I was raised Catholic¹, and I only remember that it’s my father’s birthday because my mother would joke about how he thought he was Jesus.

Almost 20 years ago, I left my father sitting in a Country Kitchen, at a table with empty plates and an unpaid check. I was 16, and doing this was supposed to be some kind of grand, emotionally charged act—telling him that I no longer wanted to continue what little visitation we still had at that point.

It came out all wrong, though. It was rushed—delivered in a nervous jumble after we had finished our meals. It ended with me saying, “And if you don’t mind, now I’m going to go.” I got up from the table, leaving him with a blank, possibly confused look on his face, walking out of the restaurant, never looking back.

Since then, I can count the number of times I’ve seen my father on one hand: my high school graduation, an awkward dinner shortly before I left for college, the first play I was cast in during my sophomore year, and then college graduation.

I have spoken to him on the phone once, slightly over a decade ago, when he called me out of the blue on a Sunday evening to tell me that his mother—my grandmother, I suppose—had passed away.

For many years now, we correspond through irregular emails, with months passing by before the next one arrives.

We are not close.

Keep reading. There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

I don’t understand the mentality of wanting to be a parent—to have that need, or desire. I’m not sure where it comes from. Perhaps people think that’s just what they are supposed to do: go off to school, get a good job, settle down with a spouse, and then begin ‘a family’ in the traditional sense of the word.

The very idea of being a parent, and everything that comes along with it, is an exhausting one when I think about it. I’m not sure where parents find the energy—and there are times when I am certain they aren’t sure where they find that energy either. Whenever I see mothers and fathers out with their children, they seem so tired. Sleep deprived, sure, if the kid is young enough, but it’s more that they seem tired in a world-weary, beaten-down kind of way.

I’m not sure where a parent finds the energy to care—not just for the life they’ve selfishly brought into the world, but about what that kid is going to be interested in and want to talk to them about. Once, at work, I encountered a woman who had a young boy with her. He was clutching onto her mobile phone, not looking where he was walking, and she was trailing behind him. Since it’s in my job description to do so, I asked her if there was anything I could help her find. She took a moment, then said, “No. Not unless you can tell me where the Pokémon are.” There was a look in her eyes—a sadness—that screamed “Please kill me.”

It is a moment like this that makes me feel remorseful for everything I subjected my parents to when I was young—every action figure I told them about, every comic book I explained, every drawing I doodled, and just had to show them. Every stupid movie for kids, I made them suffer through. I’m sure that I tested their patience, and that it took everything they had within them not to say, “Holy shit, kid, I don’t care,” because I’m almost certain that’s what I would say if I were in their position, because I am confident I do not have that kind of compassion and tolerance within.

I can’t fathom this level of patience and energy now, but maybe it just happens when you become a parent to a human child—maybe you unlock all these abilities and all this potential you never knew existed within. Maybe you find yourself becoming a more patient, tolerant, and compassionate person. The kind of person who listens, and instead of feigning interest, is actually interested.

The thing about having a child is that I don’t understand why people think they are so great that they need to create a smaller version of themselves. I’m narcissistic enough to be charming for a few minutes at a time in a social situation; however, I’m not narcissistic enough to think that I am just so amazing that I need to make more of myself. My genetics are very badly damaged, and I can’t see the reason why I’d want to pass that along.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th. This year, he will be 63 years old.

My parents were married in 1974, and I was born in 1983—what those first nine, childfree years were like for them, I do not know. My mother filed for divorce in 1995.

For most of my father’s career, he was an engineer, and even now, I still have no idea what an engineer actually does. When I was very young, he worked for the Thermos Company, which meant that during the 1980s, he brought home a lot of free, plastic lunchboxes with licensed characters on them—like Batman, the ‘real’ Ghostbusters, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Maybe a year or so after my parents divorced, he took a job working for the Ertl toy company, based out of Dyersville, Iowa, the same very small farming community where a bulk of Field of Dreams was filmed. He moved to Dubuque, the closest large city. Within a few years, he moved to Wisconsin—I don’t remember why; then to Indiana for a number of years, and most recently, Tennessee.

He sent out an email within the last month—not just to me, but to a number of people, including his siblings and their children, who, I suppose, are my aunts, uncles, and cousins—family that I haven’t seen or spoken in to in decades—stating he and his second wife had sold their home in Tennessee and were going to be living in a motorhome. “Kind of like tiny home living,” he explains. “Trying to make life a little less complicated.”

We are not close.

* * *

I don’t have a lot of bad or good memories of my father—I’m not sure that I have a lot of solid memories of him at all. Just fragments and moments, the context long forgotten and the edges blurred and faded from time.

I remember the collared shirts, ties, and slacks he would wear to work, promptly changing into an old pair of blue jeans when he came home shortly after 5 p.m, and the way he rarely sat on the couch, but would favor sitting on the floor in front of it, his long legs stretched out and crossed at the ankle, sticking out into the center of the living room.

I remember the overpowering scent of his Speed Stick deodorant when he’d come into my room to say goodbye before he left for work in the morning, and I can recall the thick, revolting smell of the ‘tropical mist’ scented Glade Plug-In air fresheners he used in his extraordinarily small, dumpy apartment—the one he hastily moved into during the divorce. The scent was so strong that it would linger on my clothing and in my hair once I returned to my mother’s apartment following weekend visitation.

I remember short games of baseball and football in the backyard, and basketball in the driveway. I remember his long Sunday morning walks out of the neighborhood, down to the nearest gas station to buy the Sunday Chicago Tribune, and how in the arts section, he read about Liz Phair, Urge Overkill, Veruca Salt, Red Red Meat, and Smashing Pumpkins.

I remember his dirty beige station wagon with its shit brown interior, and how one cold winter morning, when he was driving me to school, smoke started to billow out from somewhere in the dashboard.

I remember the sparkling waters he always drank, and how, when I had a La Croix for the first time as an ‘adult’ in college, before I took a sip of it, I thought, “I can’t believe I’m drinking this.”

I remember that, when I was around 10, he was tasked with giving me ‘the talk.’ But we had cable when I was a kid, and I had friends who had older brothers, so there wasn’t much of it that was new information to me.

I remember waking up one August morning in 1994 to a closed bedroom door, hearing my parents having a very tense discussion in the other room. I listened for a very long time, trying to make sense of what I heard—I couldn’t figure out if they were having a discussion about somebody else, or if they were having an argument. I stayed in bed for what felt like an eternity, and waited through an extended period of silence before getting out of bed and pretending I had just woken up.

I wrestled with this for months before I finally said something to my mother about overhearing them, as in her old, gray Pontiac hatchback, in the parking lot of a K-Mart.

There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

Becoming a parent—I mean, choosing to bring another life into this world—is a huge investment, and the payoff in the end isn’t guaranteed. It’s not promised that, despite all your efforts, everything is going to turn out for the best. There is the risk of birth defects or developmental disabilities; the threat of passing along your debilitating depression and anxieties, or other, more severe mental illnesses. There is the possibility that, even if you give them everything, and you try your hardest, they will still turn out to be an ungrateful little shit, and you’ll spend your days agonizing over where you went wrong.

There are moments when I can see how taxing it is emotionally to be a parent. It puts you on edge constantly, and anything, no matter how small or insignificant, could be the thing that sets you off. I watched a teenage girl bump into a case in a bookstore; the force of her movement knocked a book that was on display over, sending it to the ground. Without any warning, the girl’s mother spins around and, in a harsh whisper, hissed, “WHAT IS THE MATTER WITH YOU?” to her stunned daughter.

I watch the easily agitated father of two young children. In the grocery store, he holds a plastic produce bag open, commanding one of his children to take the cabbage from the shelf and place it in the bag. The child isn’t listening at all; in fact, the child is toddling in the opposite direction of this man, who suddenly barks, “Are you going to come over here and do this or not?”

I watch the young, conservative couple, lugging around one child who can’t be more than two, with a newborn now in tow—the man and woman who cannot be out of their early 20s, argue with one another as they shop; if they aren’t arguing, they trudge in silence, looking absolutely miserable, as the older of their children speaks incessantly to no one in particular.

* * *

My father remarried in 1997—either the day before, or the day after Valentine’s Day. It was a courthouse thing, and for some reason, I didn’t think it would last. But they are still together, now living in a mobile home to make things ‘less complicated.’

My father’s wife is the first person I ever heard use the word ‘nigger.’ I was young—probably 13, so I had obviously heard it used in rap music, but I had never heard another person that I knew use it. We were eating lunch—the three of us—and I said something about wanting to see the Martin Lawrence and Will Smith movie Bad Boys. My father’s wife, without so much as batting an eyelash, turned to me and told me she didn’t want to watch any of ‘those nigger movies.’

One of the first times I interacted with my father’s second wife, the three of us were going out to dinner. It was a Mexican restaurant, and I had ordered a bean burrito. After we placed our orders, she exclaimed in a loud and jovial voice ‘Beans make ya fart!’ I was mortified, and never really sure why she said this to me—was it some kind of forced effort on her part to try and identify with the teenage son of the man that she was involved with, or was she really just this crass?

* * *

When my wife and I were getting married, I had made it clear that we were not going to invite my father to the wedding. There may have been a small moment of deliberation on my part because the decision was one of minor contention for my soon-to-be in-laws, specifically my mother-in-law, who had a difficult time wrapping her head around why I didn’t want him there, and was certain I would regret not including him.

Others supported my choice, but I had been warned that there would be a time when I would have to tell him that I had gotten married, and that we had purposefully chosen not to invite him. That time arrived a little sooner than I was anticipating—maybe a month later.

He had sent one of his ‘Hey, how are you doing’ emails, and I’m not even certain why I was so moved, at this point, to confess—if anything, I should have waited until I had a better grasp on how I’d handle it, because I certainly was not prepared for his response.

There is a monster at the end of this essay.

* * *

For 15 years, I resented my father. I was aware of how emotionally abusive he had been to my mother before they separated. He was cold and distant, and as a child, shuffled off to his apartment every other weekend, I felt like he wasn’t trying very hard. I blamed him for the distance that had grown between us.

I thought that he was the monster.

To my surprise, he had been carrying around resentment for 15 years as well—but toward me. He felt like I had never been trying very hard, and he blamed me for the distance between us.

I was the monster.

I was the ungrateful little shit, and my father had spent his days agonizing over where he had gone wrong.

This was all revealed to me over a series of lengthy, accusatory emails that were sent after I told him I had gotten married and we had intentionally not included him. He was hurt by my decision—a feeling I truthfully had never thought he was capable of, but he was. At one point, his wife wrote back to me, implying she was reaching out to be unbeknownst to him—though they are the kind of couple that shares an email address, made up of their initials and a bunch of numbers.

During our exchanges he told me that if I really wanted to work things out, it wouldn’t be through email—it’d have to be over the phone. We’d have to have a real conversation about where things were, and how to move past it. It was either that, or things could stay the way that they were—strained and unresolved.

At the time, I didn’t have it in me to pick up the phone and have that kind of a conversation with my father, because I didn’t know what to say. I still don’t—I don’t have it in me; I don’t know what I would say. Things are still strained and unresolved. That was my choice, and I cannot imagine where I’d find the interest in repairing things.

We are not close.

There is a monster at the end of this.

* * *

It turns out I have two slightly more solid memories of my father—one of them is good, the other is not.

When I was probably eight years old, my father took me sledding. Growing up, there had been an unsanctioned sledding hill next to a Wendy’s, but someone had gotten hurt pretty badly, and the property was pretty much off-limits after that. Instead, we went to one of the city’s parks. I remember it was crowded, and difficult to find a space of your own to use as you glided down the hillside.

I was going down the hill, and I must have lost control of what I was doing, and I crashed right into a large, frozen bale of hay. The way I remember it, I may have been briefly knocked out from the impact; I can recall coming to, and just losing it completely—screaming, crying, terrified. I am certain it was an unsettling sight to witness for everybody else. My father ran down the hill, scooped me up, and took me back to his car, driving me back home as I tried to calm myself down.

It was a Saturday night, and my parents had rented the movie Tombstone. I was 11 years old, and this was shortly after the conversation with my mother, in her car, in the parking lot of a K-Mart.

I was in my room, with the door closed, trying to watch television—but I couldn’t hear it because the movie my parents were watching in the living room was too loud. Loud like my ear was pressed up against the speaker and the volume was up as high as it could go.

For a while, I wasn’t sure what to do, but after straining to hear the shows I was watching on Nickelodeon, I opened my door and wandered down the short hallway into the darkness of the living room. “Would you be able to turn down the TV, please?” I quietly asked.

My father turned his head very slowly, took a moment, and then responded, “Only if you turn down yours.” Then he went back to watching Tombstone.

I can remember that I wasn’t really sure how to respond, so I turned around and went back into my room. A few moments later, my mother came in to check on me and apologize. She said she had no idea my television was even on; she thought I had been asleep.

There is a monster at the end.

* * *

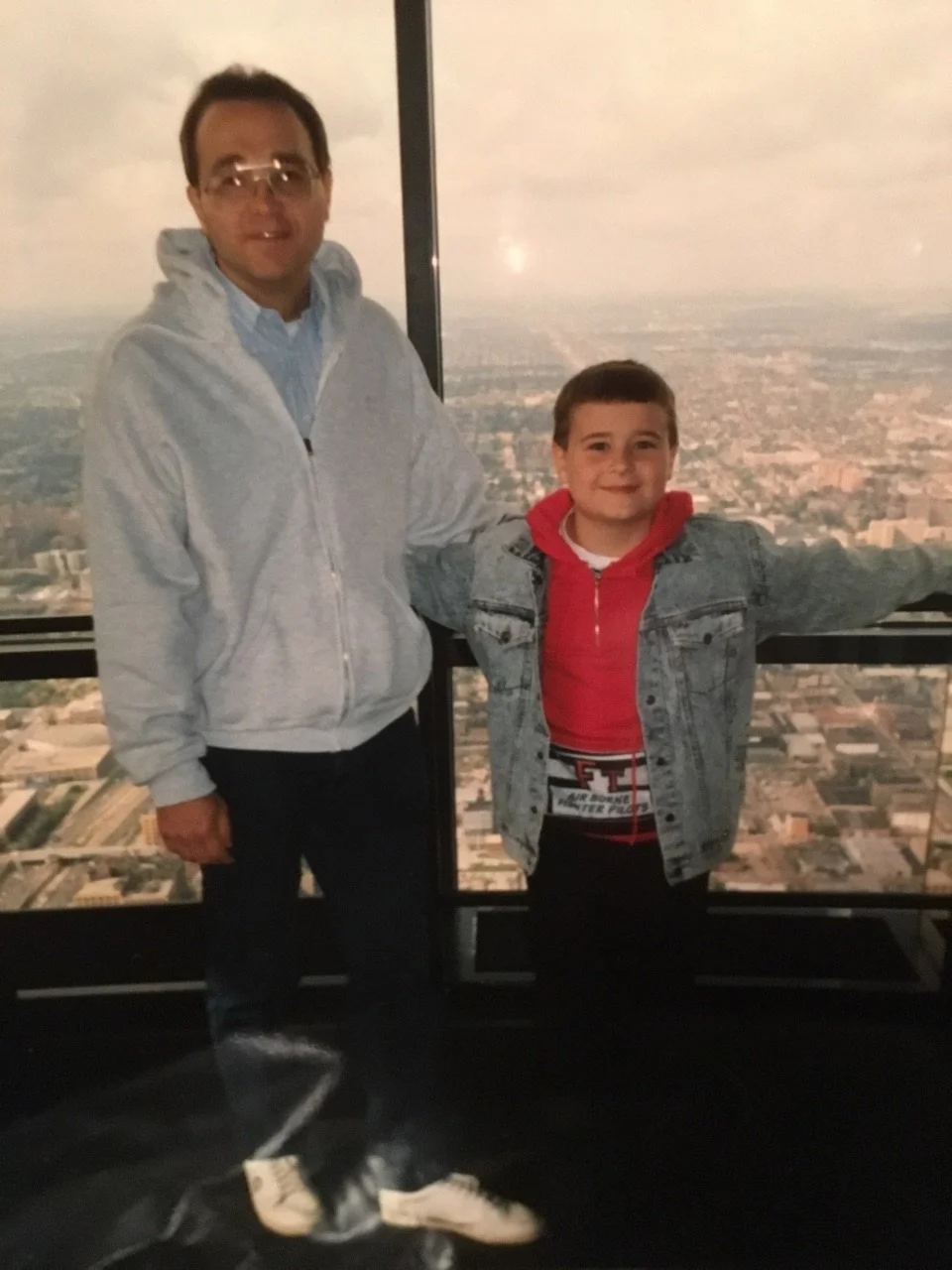

When I was in my final year of college, I was in a writing class, and one of our assignments was to take an old family photograph and write something based around it. The assignment was given to us shortly before a holiday break—our professor presumed many of us would be traveling back home and would have access to these kinds of artifacts.

The photograph I used was of me and my father at a pumpkin patch—I’m probably around seven years old, wearing a Darkwing Duck fanny pack; my father, stuffed into his old, thick, faded denim jacket. As part of the assignment, we were to bring the photos in for the rest of the class to look at. So many of the other students were quick to comment on how much I looked like him.

Occasionally, I see it—I’ll catch a glimpse of myself and I’ll see it in my small, sad-looking eyes, or when I run my hand over the top of my bald head. I didn’t make it out of my 20s with a full head of hair—my father at least made it into his late 30s before it really started thinning.

I’ll think about it when I realize that I, too, favor sitting on the floor, legs out stretched and crossed at the ankle, rather than sitting on the couch.

* * *

My father’s birthday is December 8th. Some years, I neglect to send him a ‘Happy Birthday’ email. This year, I remembered.

There are times when I forget about my father entirely; there are times when I wonder if I will ever see him again. There are times when I wonder if we were to pass one another on the street, would I recognize him? Would he recognize me?

There are times when I say that I am too irresponsible to be a parent, or that I would be a horrible father—my wife is always very quick to dispel this. She tells me that I would be good, and that I only think these things because of how badly things turned out with my own father.

She tells me that I wouldn’t be like him.

I would like to believe that, but there are moments when I am not entirely sure.

We’ve reached the end.

And, there is a monster.

1-The really great thing about Catholicism is that it’s almost entirely based around fear and guilt. So that, even as an adult, when you’ve come to the conclusion that there is no god and organized religions are a joke, if you were raised Catholic, you are still, despite your best efforts, unable to shake the feelings of guilt and fear that accompany nearly everything you do.