From The Archives: I Was An Extra In A Hallmark Holiday Film

Foreward (November, 2025)

The title ended up being changed by the time it was released. It’s called Love Always, Santa. And it’s currently available to stream a number of places. And maybe it will surprise you, or, maybe you will not be surprised at all, to learn that in the last nine years, I have not watched this film.

This doesn’t come up very often anymore, and it is a story that, like so many, I am not often that interested in sharing. But, a decade ago, a large portion of a holiday film was shot on location in my town—Northfield, Minnesota. At the time, and I guess rightfully so, it was a big deal. It is still, for some, a big deal—or of continued importance. Specifically I am thinking of the coffee shop that was used as one of the main locations in the film—every year, during the holiday season, they host a screening of Love Always, Santa; and on the wall, near the entrance, there is a framed piece of memorabilia from the film for you to look at while you wait in line to order.

But. I have not watched this film. And to the disappointment and frustration of my best friend, who thinks it is endlessly charming and fascinating that I was an extra, and had been granted access to the production of the film, I do not even have a timestamp for when I appear, briefly, on screen.

Filming took place in Northfield during January, 2016. And the movie itself was released in December of that year, originally via The Hallmark Channel. Prior to its television premiere, the film’s production company coordinated a screening in Northfield—by then, I had left my position at the newspaper and was slowly easing my way into a new job. I remember the morning after the screening (I, you may be surprised to learn, did not attend), one of my co-workers, who I did not know all that well yet, stopped mid-sentence, looked at me, and said, “Were you in that holiday movie? You were really good!”

But. I have not watched this film. I do not even have a timestamp for when I appear, briefly, on screen.

From the end of 2013, until the autumn of 2018, I regularly wrote short personal, observational pieces that were published in am monthly arts and culture paper—the SouthernMinn Scene, and then, online for a similarly minded site—The Next Ten Words. Save for the original documents on my laptop from this time period, and the physical copies of the SouthernMinn Scene I held onto, little if any trace of this era of my output still exists today.

Part of the appeal of having a website was the idea of republishing certain pieces—not rewriting or revising. It is extremely humbling to revisit my work from a number of years ago. But. It is a reminder of how far I have come, on the page, in the interim, but also where I was hoping to go, or the voice I was working towards adopting at the time it was written.

I wrote two pieces about Love Always, Santa—both of which were published in the SouthernMinn Scene. The first, “Quiet on The Set,” was written outside of my role as the “back page columnist” for the publication—it was a standalone piece that I had been asked to contribute once it was confirmed that production of the film would be taking place in Northfield. The second, “Extra, Extra,” was written for the column I had been given, “The Bearded Life.”

It is extremely humbling to revisit my work from a number of years ago. These are both, of course, products of their time—written in a contrarian, snarky voice that, a decade ago, I believed to be charming. If anything, I am grateful I no longer believe that to be true.

Quiet on The Set

An Introduction

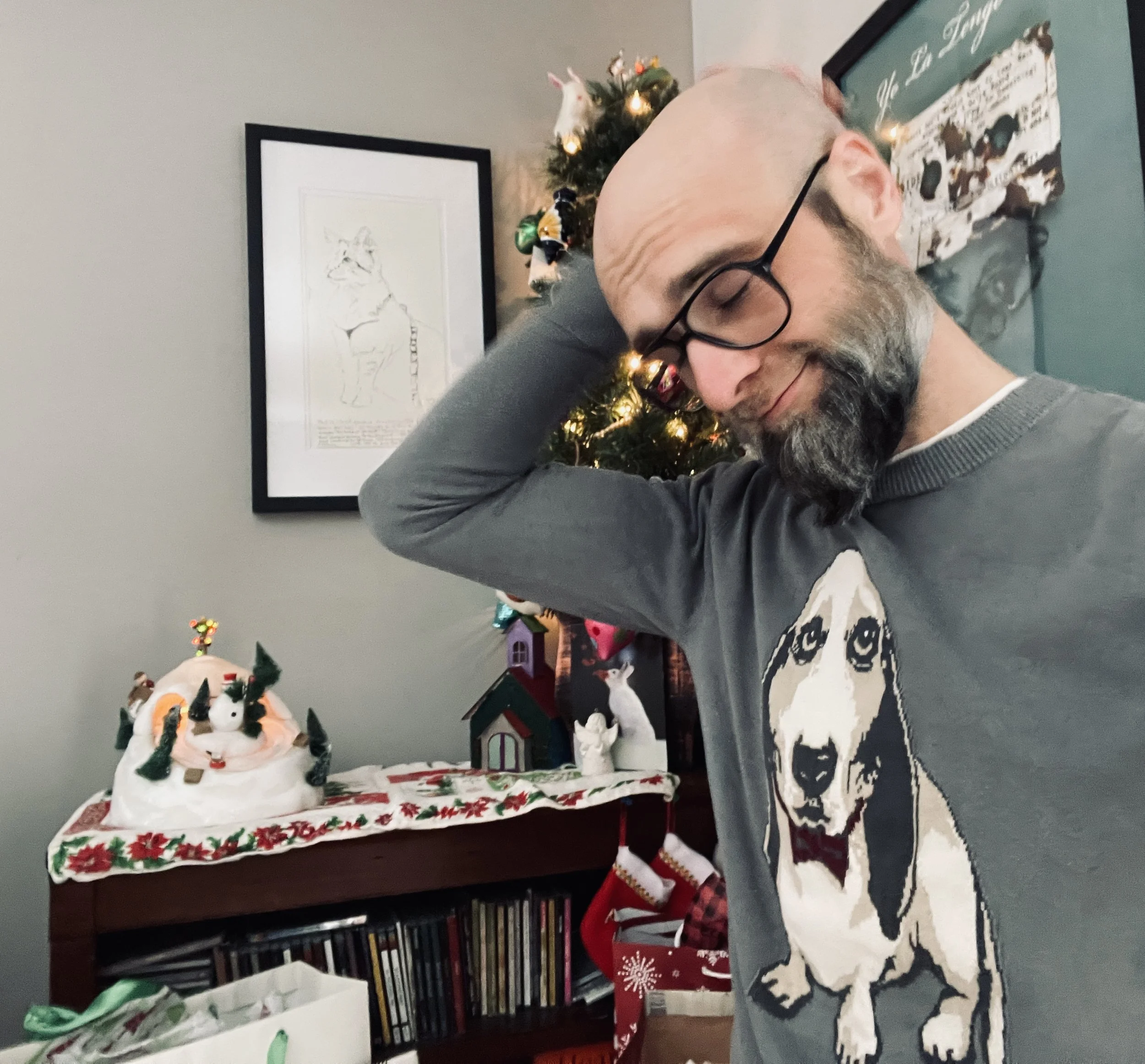

I was the guy who wore the dog sweater.

Let me explain.

The morning I meet with Mike and Lori, the producers, and with Brian, the director, I was wearing a sweater with a dog on it—a sweater I save for special occasions, like my wife’s office’s Christmas party, which I was attending later that afternoon.

The meeting was somewhat impromptu, and a topic of conversation, outside of the prospect that the trio was going to be filming a holiday romantic comedy in Northfield, became my sweater—a sweater with an illustration of a sad-looking basset hound wearing a bowtie.

This is how I became known, and identifiable in other situations, like when Mike saw me a few days later at my other job at the bookstore in town, he said “I didn’t recognize you at first without your dog sweater.” Or, later, once production was underway, Brian, after greeting me, would ask, “You got your dog sweater today? No?”

A positive way to look at this was that at the very least, I was memorable—if not for my winning personality, or my glorious beard, then for my fashion sense, or lack thereof, depending on your feelings about sweaters with illustrations of basset hounds on it.

The Movie

The movie’s called The Last Love Letter, and when I describe it as a “holiday romantic comedy,” it’s a polite way of saying that it’s going to be a made-for-television movie that will air on either Hallmark or Lifetime or ABC Family sometime near Christmas.

If you are familiar with holiday movies that air on these networks, then you’ll understand that the plot sounds very familiar—like the combination of a couple of movies that you may have already watched—A young widower owns a bookstore/coffee shop called “The Bun Also Rises.” Her daughter writes a letter to Santa, asking for her mother’s happiness (in the form of a new boyfriend) for Christmas.

The letter is intercepted by Santa Ink, a company that specializes in responding to children’s letters to Santa. The task of responding falls onto a children’s book writer suffering from writer’s block. He’s moved by the child’s letter, apparently, and writes a long letter back that this young widower reads, who then writes back to him. The two strike up some kind of letter-writing relationship (hence the title), and he travels a great distance to find her, because they are in love, or something.

And of all the locations in the world they could film The Last Love Letter, they picked Northfield—seduced by its small town charm.

The “Movies” Issue of This Magazine That You Are Currently Reading

With a tight shooting schedule for the film, the crew started production on January 11th, and were in Northfield for two weeks, filming at various locales in the downtown area.

And wouldn’t you know it, the March issue of the Southern Minnesota Scene magazine is “movies”?

And wouldn’t you know it, the deadline for content is January 29th, and that’s how yours truly ended up with this assignment, because my editor thought it would be hilarious to turn me loose on the set of a movie¹, and write something pithy about the experience, despite my crippling depression, general anxiety, overall anhedonia, and the workload that I have for my day job as a writer for the Northfield News.

“Find out what a key grip does,” he said to me, and chuckled, while I sat in his office.

Despite What You Think, I Cannot Get You A Part in The Movie

Because I wrote the original story about the movie being filmed in Northfield once it was officially announced back in early December, and because my office phone number is associated with the story on the online version, I received a lot of calls—like, a lot of calls, from people asking me how they can get a part in, or audition for, The Last Love Letter.

“Have You Ever Been on The Set of A Movie Before?”

Despite what I originally thought, name-dropping the producer and flashing my press pass does not get me onto the set right away. I have to wait to be escorted through the doors of the travel agency building by the Line Producer, Jillian. I wait in the crew’s warming tent, set up in a parking spot on Division Street. The tent smells like propane—it’s what is used to run the devices currently generating heat. It’s also where the craft services table is—a paltry smattering of cheese, little powdered donuts, coffee, and bagels that are strewn about on a card table.

Once filming has temporarily halted while people move things around and position cameras, I am quickly escorted onto the set, and am sandwiched between the end of a desk and a wall—out of the way of all the teamsters who are carrying various lighting rigs, ladders, and other equipment.

“Have you ever been on the set of a movie before?” whispers Jillian, as she scrolls through her phone, seeing there is something more important to be dealing with than a writer from the Northfield News.

I tell her that I have not, and she proceeds to point with her eyes, and expects me to follow along, to whom everyone is, and what they are all doing. I am certain that at least one of them is a grip—possibly the key grip. Though she does not identify who, if anybody, is the best boy.

At this current moment, everyone is rushing to set lighting for a scene where the male lead is reading a letter (the last love letter?) at his desk when he takes a phone call from his agent. The scene itself is probably less than five minutes in length, but has taken upwards of 15 to 20 minutes, or more, to prepare for.

Eventually, the actor, Mike, is in place, his face an unnatural shade of dark beige from all of the foundation he is wearing. As things are being finalized, before the camera rolls, I think to snap a photo on my phone—something to accompany this very story.

“You can’t take a picture of the actors,” Jillian scolds me.

I put my phone away, and never take it back out.

Coffee

“I have an odd favor,” asks Mike, the actor, to Brian, the director.

This is later, when I am sandwiched in the back of a tiny office in the travel agency—this is where the camera monitors are located, and where Brian calls action, or cut.

“Can I borrow five bucks,” Mike continues. “All my cash is in holding and I need to get a latte or something. I can’t drink any more of this coffee.”

Brian pulls out a thick, leather wallet and peels off a five-dollar bill for his actor, but then the crew announces they are ready for the next shot—the same scene they’ve been working on, just filmed at a different angle.

Mike sits back in the chair, pretending to read the same letter he has been reading, pretending to answer the phone at the desk when the assistant director says “ring ring” from off camera.

I leave shortly after this take is completed. I never find out if Mike gets his coffee.

Observing and Reporting

I find that, once people notice me on the set or are aware that I am from the Northfield News, I have to explain myself—like, what, exactly, am I doing there.

I tell people that I am observing and reporting, and that I also write the humor column for the Southern Minn. Scene magazine, and that my editor at the magazine wanted me to write something about being on the set of the movie.

I also find that even though I have a reporter’s notebook open, and a pencil in hand, I do not write much down in it, save for a tally of how many times I was asked if I was wearing my dog sweater, that I am not to take photos of the talent, and that a production assistant was, for some inexplicable reason, tearing up pieces of paper for the entire time that a shot was being set up, only stopping when it was time for cameras to roll. The sound of scraps of paper being torn and placed into a cardboard box became incredibly distracting and somewhat unnerving.

I, for whatever reason, felt this was an important detail to note.

I also note that it takes roughly an hour to 90 minutes to prepare for a scene that equates to less than a minute of screen time.

Magic

Why are we so infatuated with the entertainment industry?

That’s the question I asked myself after two short visits to the set of The Last Love Letter—once, while the crew was filming in a travel agency that was converted into the office of “Santa Ink”; the other, watching a short scene filmed in my wife’s office building.

Like, what is the allure that draws us to film, and to think that the set of a movie is some kind of magical, romantic idea?

Because from what I observed, it’s not magical or romantic. It’s mostly just a lot of people wearing carpenter jeans, standing around, waiting to move pieces of equipment when they are told to set up the next shot. Like, a lot of standing around and a lot of waiting. And then, suddenly, when it’s time to work—everybody snaps to it, and begins to hustle—holding onto their boom microphone, positioning something with the lights, touching up foundation on an actor’s face.

But we, as a culture, are captivated by the entertainment industry because of its mystique. When we watch a movie, or a television show, we don’t see the key grip, or the best boy. We see a beautiful actor hitting their mark and delivering their lines. There’s the willing suspension of disbelief that there isn’t 30 or more people, standing behind the camera, making it all happen.

For us, this is exciting. But to the assistant director, who takes himself way too seriously, barking out orders to the rest of the crew—to him, this is just another day of work.

This is what he does for a living.

And to us, it just happens to be slightly more exciting in comparison to our own lives.

A slight aside: in my original interview with Mike, Lori, and Brian, on the day I wore the dog sweater, the role of the female lead had not been cast. In making table talk with the trio at the Chamber of Commerce (where the interview took place), the president of the Chamber, Todd, said he was excited at the possibility that Danica McKellar might be in the film—the woman best known as Winnie Cooper from “The Wonder Years.” The story my editor originally was for me to try to have coffee, or something, with McKellar, and that the story would be called “My Date With Winnie Cooper.” This obviously did not transpire.

Extra, Extra

Believe it or not, my editor has the unfortunate job of fielding complaints that we occasionally receive about my monthly columns—usually they come in after I’ve used a swear word or following the time I wrote about my sister-in-law buying a marijuana cookie in Colorado.

With my January column discussing how I no longer believe in god, and February’s column featuring not one, but two utterances of profanity, I expected the conservative, delicate readers of the Southern Minnesota Scene to come out in droves to complain.

For once, I was hoping they would—because then I’d have a topic to write about for the “art” issue.

But alas—they did not. So now I have to write about my experience as an extra on the set of a movie.

You, as a reader, certainly follow along with every profanity-filled piece I write for this magazine. And because that’s the case, you are aware that last month, for the “movies” issue, I wrote a #longread about my time observing on the set of the movie that was filmed in Northfield—The Last Love Letter.

Not ten minutes after I sent my completed article, “Quiet on The Set,” to my editor for his perusal, I received a telephone call from the woman who had been tasked with corralling extras for the movie.

On the phone, she tells me that the producers of the movie like both me, as well as “my look,” and she asks me if I would like to be an extra in the movie.

Walking down Division Street, listening to her ask the question, my mind immediately goes to the place where I keep all of the excuses I would use to get out of something like this—“I don’t know if I can spare the time away from work” being the first one I use; following that, “I don’t know what my schedule is like for the week.”

The first mistake I make was telling my wife that this phone call transpired—she herself had been used as an extra when the crew filmed in her office earlier in the week. She also has an interest in filmmaking, performs in local theatrical productions, and is generally better about doing things, or showing interest in things, when opportunities like this present themselves.

I, on the other hand, thanks to my crippling depression, anxiety, and overall anhedonia, did not gaze upon this opportunity as fondly. Due to all of my…conditions…it turns out I am just not usually up for doing things that take me out of my comfort zone, or the routine that I have created for myself.

If I can quote the rapper Earl Sweatshirt—“I don’t like shit. I don’t go outside.”

Despite the fact that I don’t like shit, on a Monday morning at 6:30, I found myself outside, in below-zero temperatures, walking into the production company’s make-shift office, in what I will later discover is referred to as the “holding” area—basically, a section of the office with some folding chairs set up.

It was there I was corralled with the other extras who had been called for the day—children mostly—squirrelly, sleep-deprived children who were being wrangled by their agitated and equally as sleep-deprived parents. Children fumbling with headphones and iPads with cracked screens; children manically mashing on the touch screen of their parents’ smartphone, playing some kind of mind-numbing video game.

After sitting uncomfortably in a folding chair for an hour, we extras were all corralled from holding, across the street to where the shoot for the day was—the bookstore.

This is where I make my second mistake in this entire comedy of errors—as the director sidles up to me and we make small pleasantries, I mention to him that, outside of my work with the paper, I also work at the bookstore. As these words leave my mouth, I see the gears beginning to turn in his head—he decides he’s going to use me as a featured extra—where I am to place a sign in the window of the bookstore, advertising an in-store author event, that then attracts the attention of a child actress.

This means that I am not needed until 11:30, which means I sit around for four hours with nothing to do—save for wallowing in my anxieties about the situation. I didn’t think to bring something to do, like a book to read, or my laptop. Instead, I think about how I should be working. I wonder about if my boss will even approve the vacation time I put in a request to use so I could be here. I hope that I’ll be done before 12:30 p.m. so I can go home and check in my rabbit—something that I do, like clockwork, every weekday.

Finally, after hours of waiting and anticipation, it’s my moment to shine. A production assistant is sent over to the holding area and summons for me.

Place in the store, I am handed an oversized sign that advertises the author event, and am given little, if any direction about what to do—when I’m told, I am supposed to place it in the window, futz with it for a second, and then wave at the little girl starring in the movie.

And I do all of that. And then I do it all again. And again. And again.

That’s one of the things you don’t realize about movie making—you don’t just do something once and move on. You do it once for the camera that’s behind you. Then the crew resets, and you do it again for the camera that’s in front of you on a dolly track, moving from left to right. Then you do it again for a different camera that is also in front of you, but not moving. Then you do it again for yet another camera that is positioned slightly behind the other one.

You continue to do all this. You place the sign. You futz. You wave. The director calls “Cut. One more time.”

And it’s not just you, the director has his hands full with—he has to deal with child performers, one of whom is failing to deliver the lines in the way that he’s rehearsed with the kid just moments prior to yelling “action.”

“Say it just like that,” he tells the child.

The child does not say it just like that at all.

You reset the shot. You place the sign in the window again.

Eventually, my anxiety subsides, and I’m left with a feeling of irritation—I’m frustrated that I am still on the set of a movie, having spent upwards of six hours total in a holding pattern of waiting for this moment—the moment where I place a sign in a window and wave to a child I’ve never met, and don’t even talk to.

After enough times through, it’s determined that they got the shots they need. “That’s a wrap on Kevin,” I am told by one of the dozens of production assistants, scrambling around the set with various lighting rigs, camera mounts, and walkie-talkies.

Once I am dismissed from the set, I wander back to my office, only to be greeted with jokes from my co-workers: “Will you remember all of us little people when you are big and famous,” one of them deadpans.

Still frustrated from my morning, I laugh, because that’s all you can do.

As I sit down to begin my day—mid-afternoon—I think about the supposedly fun thing that I just experienced, and I wonder what, if anything, I got out of the experience and why I let myself get talked into it.

You reset the shot. You answer the phone, and when asked if you want to do something that takes you out of your routine, you say “no, thank you. I’m not interested.”