You’re So Sick—I’m So Sick of Me Too

There are similarities, each year, to how I end up approaching this list. Or, at least, what I wish to take into consideration when I sit down to assemble it.

It’s funny. There are so many people who live and die by the information Spotify provides them, or whatever streaming platform they prefer, as the year comes to a close. And that information—most listened to song, artist, etc.—that might be completely accurate. That might be how you primarily listen to music.

I stop short of saying I use Spotify incorrectly. But it is not my primary means of listening. And I guess, more than anything, a list that represents a calendar year should also be about the songs that made you think. Or challenged you in some way. Or had an emotional impact on you that, in some cases, will resonate long into the new year, and beyond.

There are similarities, each year, to how I end up approaching this list, and how it comes together, in ways both expected and not, when I am thinking about the songs I heard, the songs I liked, and the songs that meant something to me. There are the songs that are fun. Or anthemic. There are the songs that are representative of specific moments, or instances—large, or small.

There is the song that hurt my feelings the most.

*

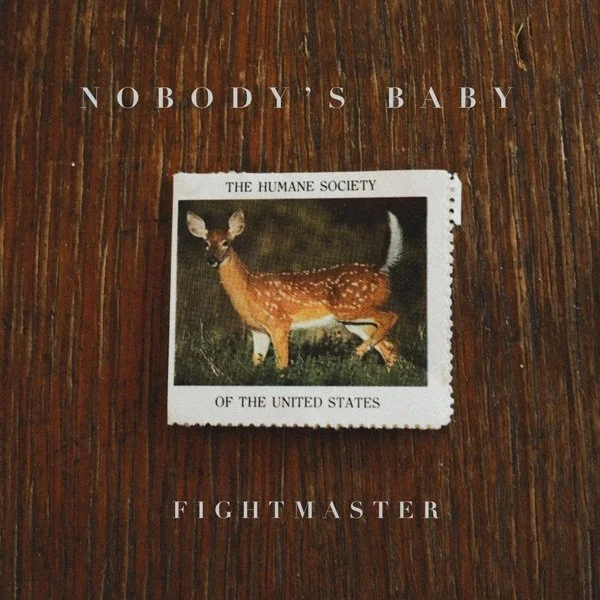

“Nobody’s Baby” by E.R. Fightmaster

Maybe I’m just a baby.

I think about that a lot, actually. Or, rather, it is the realization I often arrive at. Or an understanding, perhaps. A difficult one. The one that stares back at me, when faced with my own disappointments, or frustrations. Or my moments of unhappiness. What I understand, or realize, is that it would behoove me to be more gracious. To be much more agreeable or affable. The offer of more patience. To be a better sport about things.

And there are, of course, some things—often small, or in the end, minutiae, really. It’s these instances. These moments of disappointment. Or frustration. Passing, or fleeting unhappiness. These are the places where I could, and should, be more agreeable. Affable. The endless well of patience. Offer the graciousness required. It’s a place to start. This kind of growth. However small, or seemingly insignificant. We’re always putting in “The Work.” A kind of self-improvement, or self-discovery.

And it isn’t really a part of the internet’s colloquial lexicon anymore. Not as it was a number of years ago. And, I mean, I suppose then that I do not really think about it as often as I once did, a number of years ago. But there was a time, and maybe you remember this, but people would respond to something by saying they felt “seen and attacked” by it. It’s supposed to be funny. A self-effacing kind of reaction. I don’t know if there’s any humor left to be found in it, now. Maybe there never was, in the first place.

What I am getting at though is there was a point when, in writing about music—I think, definitely, the point where I had been doing it for around six years, and was slowly moving away from being more casual, or conversational, and growing, or inching towards, being more thoughtful and articulate. Or literate. There was this point, though, in writing about contemporary popular music, in writing myself into my analysis as a character, I found I was regularly stating I had felt seen and attacked by specific songs.

And what I meant by that was it was a song that, in its lyricism, it showed me an unflattering reflection of myself, and asked me to confront something ugly, or unsavory, that I often did not wish to.

It was a song that hurt my feelings.

Maybe I’m just a baby.

And, I mean, this is the realization I often arrive at. The difficult understanding. The disappointments and frustrations. Moments of unhappiness. I could be more gracious. Agreeable. Affable. I should and could have more patience to offer. A better sport about conversations that I do not wish to engage in because they are of little or no interest to me. A better sport about the way I am adjacently treated in social situations.

I could stand to realize, or have a better, clearer understanding of how people are often gracious with me, when I am undeserving. A herculean effort, from what I have gleaned. The patience offered. Tiptoeing around how disagreeable I can be. How I can be a baby.

It isn’t always something small, though. That’s the thing. The minutiae. Sometimes it is much larger than that. The disappointments or the frustrations or the moments of unhappiness are no longer fleeting. It all compounds. And what do you do then. What can you do. If anything.

I guess what I am getting at is that it has been a long time since I have felt so called out—so seen, and attacked—and in the end, understood, by a song, the way I have been by E.R. Fightmaster’s “Nobody’s Baby.”

When you search the name “E.R. Fightmaster,” the short description that comes up, underneath, is “American actor.” Perhaps known, on screen, for their role as Dr. Kai, a recurring character on the long-running series Grey’s Anatomy, Emmett Rogers Fightmaster, after spending time with Chicago’s storied Second City comedy group, appeared in two seasons of the Hulu comedy Shrill.

This is, and isn’t, how I was first introduced to Fightmaster.

At one time part of a musical project called Twin, with Mike Aviles, Fightmaster began releasing solo material, under their own name (just stylized, in all caps) in 2023—their debut EP, Violence, was released that same year, followed by an additional EP, Bloodshed Baby, in 2024.

My best friend, Alyssa, began following Fightmaster (specifically their musical output) after their work on Shrill, and in the roll-out of singles, in 2024, leading up to the release of Bloodshed Baby, she would speak of the new songs with a very real enthusiasm. “New E.R. Fightmaster today, Kevin,” Alyssa would tell me on the telephone. “Are you excited? Did you listen?”

I was not familiar with Fightmaster—the actor, or the musician, prior to these conversations. And something that I find to be compelling, is when you, as a listener, are able to really hear growth, or continued confidence and maturation occurring, in what is anecdotally a short amount of time.

There is a kind of nervy snarl and ferocity to the songs on Fightmaster’s first two EPs. Their voice is gentle, sure, and warm, but in terms of where it falls in the mix, there is this intentional cavernous muffling that happens, giving the songs just a little flirtation of mystery, perhaps. Or kind of alluring curiosity. And I mean maybe that comes from the thematic elements of Fightmaster’s early single, “Bad Man”—which exudes a kind of effortless and surprising sexual confidence in its lyrics.

I tell you all of that to tell you this. “Nobody’s Baby” is unrelenting and breathless, and in its breathlessness, it is a bold and enormous step for Fightmaster, in just production and arranging alone. Their voice, still gentle, and warm, is also clear, and firmly positioned near the top of the mix, escaping any kind of post-production reverberation, and it is allowed to soar in just the right moments, to convey the kind of exhaustion, frustration, and ultimately the sadness that is written into the heart of the song.

Musically, “Nobody’s Baby” is much folksier, or even a little country and western tinged, comparatively to Fightmaster’s previous efforts—the fiddle that rips through the song, at one point, as a means of punctuation, certainly offers a twangy feeling. And even though there is, like, this inherent softness, comparatively, to the song, that is juxtaposed against just how briskly paced it is—there is no moment on the song that is misspent, and it is pushed forward through the voluminous and anthemic strums of the acoustic guitar, joined then by crisp, snappy percussion that grounds the rhythm a little more, and eventually accompanied by the tasteful, subtle plucks of the banjo.

There is a razor-sharp intelligence in how Fightmaster balances this unrelenting nature, though. “Nobody’s Baby” isn’t an exercise in tension and release, really, but they know when to pull the song back, as a means of emphasizing specific lyrical moments, then allowing it to build, and build, but never truly get away from them, or ascend too high.

And it is in these moments. Where the song is restrained a little. That there is this quiet acknowledgement. A difficult truth to face. Because there is, in the end, such a humbling nature to this song, and what it does depict.

Maybe I’m just a baby.

Something that I return to, in writing about music analytically, is the idea of the “love song.” Because, yes, there are songs that are written from a place of affection—amorous, or sensual. And those are fine. Often lovely. Regularly fun. But what I am more interested in, and have been more interested in, for a number of years now, are songs that are about love. Because love is not always affectionate or amorous or sensual. Love, in any form, with whomever, presents challenges. Frustrations. Disappointments. We are asked to have patience. We wish to show one another grace.

Sometimes that doesn’t happen.

“Nobody’s Baby” isn’t a breakup song. Not really. And it isn’t a love song. It is a song about love, though. About the patience we try to have. The grace we wish to show. The places where we find ourselves falling short in all of that.

About the role we inevitably find ourselves in. And then the resentment that can come from that role.

Fightmaster has no time to waste on “Nobody’s Baby.” It is a song that moves at an unrelenting pace, with a real sense of urgency rippling and swelling throughout. It opens with one of the lines that they return to throughout—or, rather, one of the main ideas the song presents. “I think you’re going to miss me,” they sing, with clarity, as the song begins.

There is a domesticity to what is depicted throughout “Nobody’s Baby.” And in that, the disconnects that can and regularly do occur between two people. “You say you need me more gentle—I’m worried I just don’t know how,” they explain. “I grew up inside a hellfire, I’m as soft as my system allows.”

There is a turn then, that occurs—a sharp one. The song is, of course, personal, or inward turned, but this is where “Nobody’s Baby” does become startling in its admissions and revelations.

“Is it okay to feel like I’m dying as long as we’re reaching your goal,” they ask, before lamenting. “I miss the feeling of loving each other without all the need for control.”

“Call me a child, but I’m nobody’s baby,” Fightmater scowls in the song’s early arriving bridge. “You need me to smile—I’ve been faking those lately.”

There, of course, are the small things. The smallest. Minutiae, really. The banality of the day-to-day. But these instances. The moments where there is continued disappointment or frustration. The unhappiness that feels less fleeting, or passing, than it once did. The places where you are aware you could stand to be more gracious, or patient. More agreeable or understanding. It really is the most mundane, isn’t it. It always is. Just enough of it, compounding. Until you find yourself in a place of resentment that you are uncertain how to get out of.

“Who’ll buy the flowers that rest on your table?” Fightmaster asks in the second verse, with the emergent nature of the song really surging right to the top into a kind of sorrowful, gasping exhalation. “Who’ll put the milk back inside of your fridge? Who will remind you it’s five before showtime? Who will make plans with all of our friends? Who’ll take the trash out, and talk to the birds in the morning—point out the sunset and sing to the moon,” they continue. “And invite you to dinner at five in the evening ‘cause I know your bedtime is late afternoon.”

Sometimes, and it doesn’t usually happen like this. But sometimes, the weight, or gravity, of a song doesn’t hit me right away, which is what happened with “Nobody’s Baby.” Because during my initial listen, I thought, okay, well this is a very beautiful, and soaring song, that returns to this line—“I think you’re going to miss me.” But the vivid nature of the feelings depicted, and specifically why I understood them, did not come until a later listen, at what ended up being an inopportune time to have this kind of realization.

How often do you see an absolutely unflattering reflection of yourself in a pop song? How often do you feel seen and understood, but also attacked.

We do resign ourselves. Perhaps reluctantly. Or unknowingly, over time. The roles we find ourselves in. Uncertain how to ask for help. Resentful, but unable to find the way to properly articulate in a way that is constructive, and not hurtful.

Who puts the milk away. Buys the flowers. Who takes the trash to the curb. Who is the one to make the plans with others.

Who if not you. And this role, then. Or what has become expected. I am remiss to say, is this all there is. But the question that I do ask myself, and the question that Fightmaster, I think, is working towards on “Nobody’s Baby,” is, is this, in the end, all I am good for. Or why I remain.

Who if not you.

And the thing that is the most resonant, or the most reflective, is yes, the honesty with which Fightmaster writes, and sings, about this experience—these expectations and roles. This resignation. But it is also what it asks us, as listeners, to consider once the final note evaporates into the air and we’re left in a moment of not uncomfortable silence. But a silence, regardless, that makes demands of us. What do we do with this. Who if not you.

I am remiss to say the final time Fightmaster sings “I think you’re going to miss me,” that it is pained—maybe that is not the right descriptor. There is an exhausted anguish, though, that comes out, in the way they belt the line out, allowing it to easily soar above the already swelling instrumentation, and providing this opportunity for it to say, or convey so much more than there is time, and space, to explain within the confines of the song.

“Nobody’s Baby” does ask us to consider what we do, eventually, lose about ourselves. Or what is given up. And there is no right or wrong, or easy answer, in the end. What we do with this resentment. If we continue to push it further down. If we find the grace, and patience that we are lacking. And that’s the thing. As the song ends, it stops in this moment of concession. Or of self-deprecation.

“You can call me a child,” they lament, quietly, as the acoustic guitar strings flick underneath them. “Maybe I’m just a baby.”

Maybe I’m just a baby.

“Big Deal,” and “Lost Time” by Lucy Dacus

“Concept album” is a description that I, perhaps, use entirely too often and too freely, tossing it around, in a sense, when I write analytically about contemporary popular music. It would, maybe, behoove me, to use it less, or to find other ways to describe a collection of songs, arranged around what is, ultimately, a singular theme, or idea.

Lucy Dacus’ Forever is A Feeling is, of course, a collection of songs arranged around what is ultimately a singular theme, or idea. Or story. Or a concept. And by the time the record was released in the spring of 2025, the inspiration for the album—Dacus’ relationship with her Boygenius bandmate, Julien Baker, was confirmed, and no longer subjected to internet speculation as to why they were always sitting next to one another, as they often were, in photographs.

There is a non-linear way in which Forever is A Feeling moves through this narrative—and certainly, the album is about more than just falling in love with one of your closest friends. It is also a reflection on friendship, or a platonic love and admiration. It is also, at times, about not heartbreak, but when something has ended, and what it feels like to still be swimming in its wake.

The sequencing, though, to Forever is A Feeling smartly bookends it with what are, I think, amongst its finest moments. And if not the “finest,” or “best,” it is anchored by songs that exist within different spaces of the same feeling, or sensation. Even though we, as listeners, are aware of how the story really does end, there is a bittersweetness to how Dacus depicts the idea of longing in both the album’s smoldering opening track, “Big Deal,” and the fragile, human, and surprisingly cathartic finale, “Lost Time.”

“Big Deal,” in a sense, operates from a place of tension. Or uncertainty. A kind of nervousness. Not exactly the instance of realization—just a little beyond that. A moment when something difficult, but something beautiful, and full of potential, is understood and acknowledged with a the delicacy it demands.

Musically, “Big Deal” moves not slowly, but with intentionality, like a dream. Or through a haze. I suppose that’s fitting, given the kind of dreamlike way Dacus’ narrative unfolds in her writing here. It is a gentle song. And, I mean, a large portion of Forever is A Feeling is gentle, or soft. But “Big Deal” is amongst its softest. There isn’t a tension, really. Just a little drama in the uncertainty as Dacus wanders through all of her feelings, within this specific moment. And there are places where it could ascend, or soar, and it does. In a subtle way. Just the slightest lift, as a means of emphasis.

There is soothing, atmospheric undercurrent that ripples quietly underneath “Big Deal,” and the song is pushed forward, primarily, through the casual strums of the acoustic guitar, and the brushed, shuffling percussion, with the tone itself only shifting, really, with the addition of a rumbling bass line and keyboard noodling in the moments leading up to the chorus, and then the chorus itself—the repeating of the titular phrase, like a mantra, or a prayer for salvation—creating a space for the emotions to swoon, and swell. Just enough of a swirling buildup of texture, and never really getting away from Dacus, who quickly pulls it back in.

And I am, of course, often talking about the “Kingdom of Desire.” Perhaps too often. About how pop music desires a body. About want giving way to more want. About the moments we are brought to. From the moment we first hear Dacus’ voice, on “Big Deal,” we are placed within that moment. On the cusp. Something is going to happen. Something unspoken that is being explored, for the first time. A kind of clumsy admittance.

“Flicking embers into daffodils,” Dacus begins, painting an evocative portrait right from the very first line. “You didn’t plan to tell me how you feel. You laugh about it, like it’s no big deal,” she continues, before returning to the juxtaposition of the first image. “Crush the fire underneath your heel.”

“I’m surprised that you’re the one who said it first,” she continues, directly addressing the off-stage character in the song. “If you had waited a few years, I would have burst. Everything comes up to the surface in the end—even the things we’d rather leave unspoken.”

And it is hard. Or challenging. To find yourself having to address, directly, something you thought you would, as best as you could, keep yourself. The hand you never thought you’d have to play, or reveal.

What Dacus comes back to, before the titular phrase, serving as the chorus, is a kind of self-deprecating grace, and in doing so, displays a real, palpable tenderness. “We both know what it would never work,” she admits at first, before asking a few lines later, “What changes if anything? Maybe everything can say the same. But if we never talk about it again,” she confesses. “There’s something I want you to understand.”

And it is beautiful. A quiet kind of intimacy. And it isn’t limited to someone you are, or wish to be, romantically involved with. There can, and often is, an intimacy that occurs between two people who do just care, a great deal, for one another.

“You’re a big deal.”

We as listeners, of course, know how this story does ultimately end. However, within this moment, there is an uncertainty, which is why “Big Deal” is so poignant. I mean, yes, it is beautiful, and it really does encapsulate such a specific feeling—exciting and scary. But this tenderness at the end. And affection. Telling someone that, regardless of what happens, the impact they’ve had on your life. You’re a big deal.

And because there is a non-linear approach to how the story, or larger story, is revealed in Forever Is A Feeling, both in the literal sense, in how the songs appear in sequence, but there is also, like, no real “ending.” I suppose that could be attributed to the title itself. The story keeps going. Forever is a feeling.

Forever is A Feeling, though, concludes with the delicate, and extremely thoughtful “Lost Time,” which yes, it is like, the “happiest” ending an album that doubles as a love story could have. But it also is an exploration of longing—not just of who is out of reach, or what exciting, fleeting moments with someone feel like, but of wanting to know someone for who they are. The small details. The quiet moments where, there is no real silence between the two of you but there is an understanding, and a comfort.

I don’t think it’s a fatal flaw of Forever is A Feeling, but it is inherently a big-budget album—Dacus’ first as a solo artist through a major label, so it does just sound a lot larger in comparison to her other full-length efforts. I even mention this, not as a criticism, but it is, I think, important to know that even with a record this size, there are still these small instances or details, that make it feel a little more intimate, or hushed. “Lost Time,” in the way it is engineered with intentionality, is one of those places. It is a gentle, and swoony kind of song, and yeah, given what it’s about, or how Dacus’ narrative unfolds, it is just the right amount of saccharine that swirls together at the top.

Beginning with just the acoustic guitar and Dacus’ voice, we also hear the sound of birds, outside, just underneath her as a means of conjuring an atmosphere that mirrors, as it is able, the opening lines. It’s a small detail. But a thoughtful one. Or one that shows a kind of sharpness in terms of building a larger world in the studio. And Structurally, it is a song that is intelligent enough, or self-aware enough, to not slowly shuffle forward on a kind of tension, with no real release, but rather, a natural give and take, with more elements, like percussion, piano flourishes, and rolling bass lines, arriving and giving a small ascent to the chorus—and there is a kind of subtle, natural build that happens, too, the closer the song gets to its bridge, and its surprising final verse.

Even in the kind of overly sweet imagery, and phrase turns, that Dacus uses at the top of the song, they are vivid, and they work well, in the feeling she wants to create—the longing. The kind of pull someone has on you, regardless of whether you are in the same room or miles apart.

“The sky is grey, the trees are pink,” she begins. “It’s almost spring, and I can’t wait, and I can’t think. The sidewalk’s paved with petals like a wedding aisle—I wonder how long it would take to walk 800 miles to say I do, I did, I would,” she continues, with a visceral sense of yearning just simmering underneath the surface. “I’m not sorry. Not certain. Not perfect. Not good.”

She returns to this phrasing at the end of the second verse, which is far less saccharine, with the yearning, and a kind of lusty tension, boiling over. “Wish you were here—wish I was there,” Dacus sighs. “I wish that we could have a place that we could share. Not stolen moments in abandoned halls,” she continues, a smolder in her voice. “Quiet touch in elevators and bathroom stalls. But I will. I would. I did. I do. For the thrill, for my health, for myself, for you.”

Perhaps part of what it is like to release an album through a major label, with a certain amount of expectation placed on the idea of supporting, and interest remaining generated as the year continues, Dacus released an expanded edition of Forever is A Feeling, which includes an alternate, longer version of “Lost Time,” and features additional lyrics in the final verse. They aren’t imperative to understanding the real intention of the song, or this moment in the song, specifically, but there is a resonance to one of the lines, specifically, in the build-up to the truly explosive final moments.

“Lost Time” ends in a domestic scene. “Our formal attire on the floor, in a pile,” Dacus observes. “In the morning, I will fold it while you get ready for work. I hear you singing in the shower—it’s the song I showed you years ago. It’s nice to know you listen to it after all this time.”

The song, regardless of which version you listen to, careens into an unexpected cacophony, on cue, with ferocious, snarling, and crunchy electric guitar chugs and snare hits, pummeling the song forward with a torrent on the line, “I put your clothes on the dresser with your 60 day chip,” a small, important nod to Julien Baker’s continued sobriety. And this portion of the song—this more sonically volatile portion, is extended out to its breaking point, in the alternate version of the song, while Dacus strings along additional imagery. And the line, from this version that I think is the most resonant, comes right before the line in the song that is the most human. Or the most indicative of what it is like to truly understand someone, and be understood, or known, in return.

“Your face is a language—I’m fluent by now,” she explains. “You can tell me the whole story without saying it out loud. I notice everything about you. I can’t help it. It’s not a choice. It’s been this way since we met.”

Something that I am often thinking about is a piece that Hanif Abdurraqib wrote, a number of years ago, with regard to the Carly Rae Jepsen song, “Your Type,” and about the confession of affection. There is some mythology around the piece, and his reading of the piece, where he stood in front of a screen with a slide projected onto it that read, “Tell A Friend That You’re In Love With Them Tonight.”

And I mention this, because that is certainly what is at the heart of Forever is A Feeling, but it is also, really, the central idea of “Lost Time.” “Because I love you, and every day that I knew and didn’t say is lost time,” Dacus explains in the chorus, then adds, with a surprising kind of self-deprecation and sorrow, during the final exhalation of the song, describes this hesitation to be honest as a crying shame; a crime; and a waste of space.

The original, album version of “Lost Time” ends, similar to how it began, with a bit of slick, studio trickery, as the torrent of guitars and drums quickly receded, and we are left with the crudely recorded demo, from Dacus’ mobile phone—a cavernous and skeletal final sound, her voice, and the heavy strums of the acoustic guitar.

Dangerous is not the correct word, exactly, to describe this feeling. The urge to tell a friend that you are in love with them. But there is this nervousness. And uncertainty. And excitement, yes. But you are, in a sense, bringing yourself right up to the edge before something is going to happen. And you have to decide if it is worth the risk.

And, yes, both “Lost Time” and “Big Deal” are written through a romantic lens, but what is, in the end, the importance of these songs is how Dacus writes about connection. About the ways we change one another’s lives. About the small moments. The quiet spaces in between. And what the silence, or the quiet, in that space means.

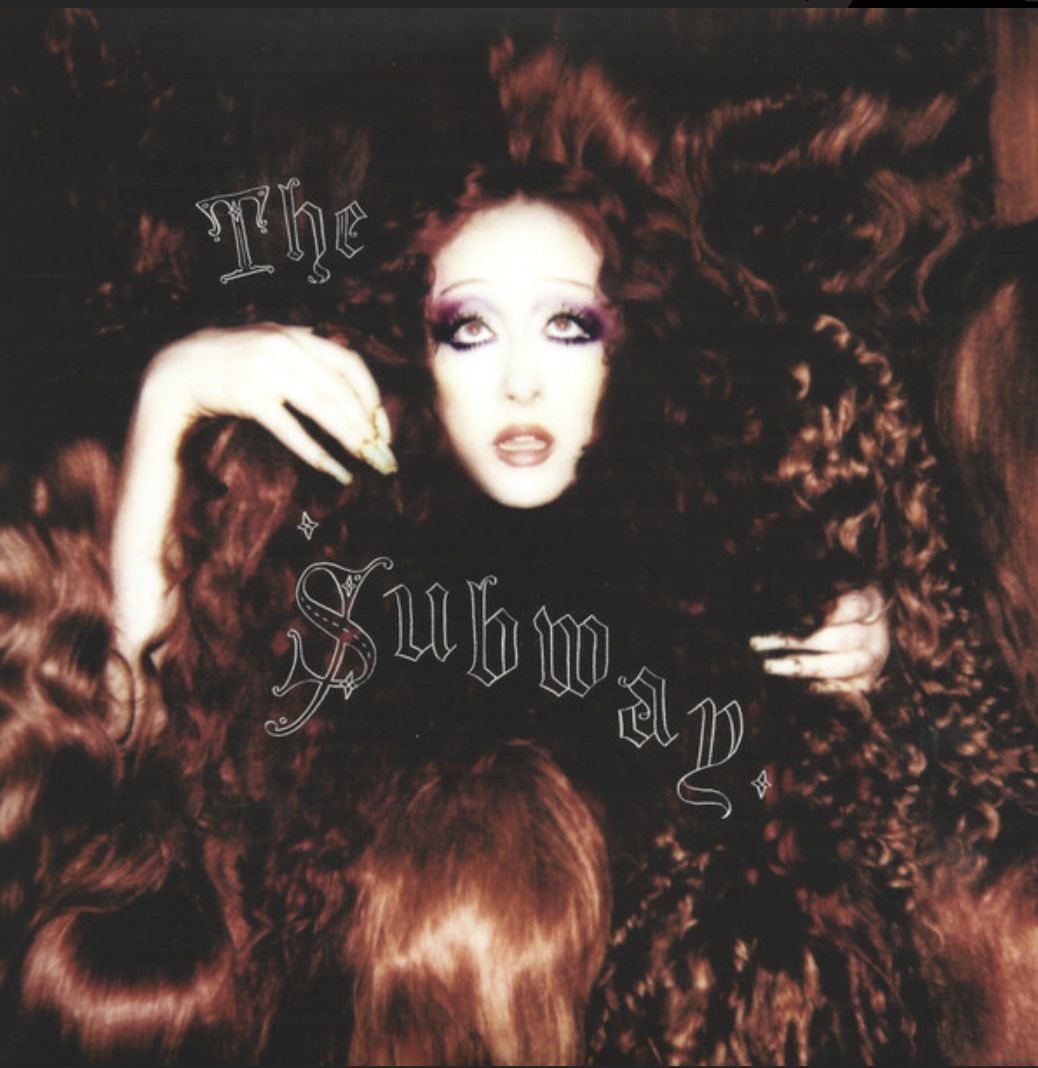

How Bad Do U Want Me? by Lady Gaga

I am not entirely certain how long it was after the release of Lady Gaga’s eighth full-length album, Mayhem, that my best friend started interjecting, without prompting, the phrase, “That girl in your head ain’t real—how bad do you want me for real,” into conversations, as like a bit, or an aside. And I’m not sure how many times this occurred, and how many times I asked her to explain, or remind me, what it was in reference to, that, in an effort to better understand, I finally sat down to listen to the song that line is pulled from—“How Bad Do U Want Me.”

I think that a few years ago, it was surprising for some to learn how much I genuinely enjoy and appreciate pop music. I guess at this point, I am not sure if this is something that is surprising about me—and the surprise, or lack thereof, is something I am not concerned with. It is of course a punchline, when used in specific instances, but we do contain multitudes. We can, primarily, I suppose, like certain things or gravitate towards certain genres or aesthetics. But we can also enjoy and appreciate something that we—meaning me, a man in his early 40s—might not be the intended audience for.

The more I sit down with pop music, and the more conversations I have, in passing, about pop music, and analytical writing, with my best friend, the more I am asked to remember that not everything—not every song, is one that is intended for a kind of in-depth dissection. Not every song is written with lyrics that are meant to be combed through for a larger, or more personal meaning. There are songs that are “vibe-based,” or really hinge themselves almost entirely on a feeling. This is not to say that pop music cannot be listened to analytically. It is just something that, more often than not, wishes to have fun. As the listener, we are encouraged to have fun along with it.

Something that I perhaps do too often in writing about music is reference the idea of “The Kingdom of Desire.” A narrative device in which songs can exist. A means of telling a story, but only bringing us, as listeners, up to a certain point. The moment just before something happens.

Want, leading to more want.

I tell you all of that to tell you this. “How Bad Do U Want Me” exists firmly within the confines of the Kingdom of Desire—enormous, dazzling, and honestly unsettling in the kind of visceral desperation it depicts in its lyrics, it is a song that, the further we are pulled, it is clear that it is on the cusp of breaking out of the confines, in the effort to get exactly what it wants, at really any cost.

Stefani Germanotto’s output as Lady Gaga, over the last 16 or so years, is firmly rooted in a kind of theatricality. She is a singer, yes. A songwriter, yes. She is also a performer. Her concerts are lavish productions, and her flair for the dramatic carries over into the artwork and aesthetic she adopts for each album. But it is hard, or can be hard, for a performer to find a way to take all of that—something visual, or something you experience, and work with it in such a way that it translates onto a recording. Germanotto is successful, I think, because she is extremely self-aware, and in the theatricality, or dramatic flair, there is also a kind of campiness that she is willing to indulge.

She also knows, as a songwriter and an artist, how to construct a pop song that works extremely well—hitting its marks with startling and razor-sharp precision.

There is a jitteriness, or a glitchy feeling, as “How Bad Do U Want Me” begins, and Germanotto works effortlessly to sustain it, and allows it to build in a seemingly organic way through the verses, allowing the song to ascend to shimmering, bold heights in the chorus, before bringing it back down again.

Because of what “How Bad Do U Want Me” is ultimately about, or the narrative that is crafted throughout, it isn’t surprising, I don’t believe, that there is a palpable restlessness that occurs from the first few notes. A deep, skittering synthesizer pattern oscillates back and forth, laying the foundation, for Germanotto’s vocals to come in, along with some other atmospheric textures, all of which rush together quickly when the percussive elements kick in, allowing the song to truly soar—and when it isn’t soaring, like this, during the voluminous chorus, she scales I back to place that doesn’t operate from a tension, exactly, but there is an urgency, or a truly emergent nature that keeps building until it is really no longer able to be restrained.

The thing that I keep coming back to with “How Bad Do U Want Me,” specifically in the moment where, from her most guttural, lower register, Germanotto delivers that line—“That girl in your head ain’t real—how bad do you want me for real,” is that it sounds like a threat, or a warning. But by this point, in the song, as it nears its conclusion, the danger, or the lengths she is willing to go to, has been well established.

Not every song, especially pop music, is intended for a kind of in-depth dissection. Not every song is written with lyrics that are meant to be combed through for a larger, or more personal meaning. Songs can be, and often are, vibe-based. Pop music often wishes to have fun. And as the listener, we are encouraged to have fun along with it.

But. A song like “How Bad Do U Want Me,” which has such an arresting, compelling narrative, is one that can be listened to analytically—how it surrenders itself to a kind of camp, and how it manages to walk a line between humor and not a humorlessness, but a startling depiction of obsession.

“The good girl in your dreams is mad you’re lovin’ me,” Germanotto begins. “I know you wish that was me,” she continues, tauntingly. “How bad, bad do you want me,” she asks. And it’s here. As she does again just a few lines later, includes this kind of campy, kind of eerie vocal stuttering sound at the end of the “me,” extending it out just a little further. It’s hard to describe, really. You kind of have to hear it, or sit in this specific moment within the song, to understand. But, truthfully, in hearing “How Bad Do U Want Me” for the first time, it was the first instance of that noise—a creeping, exhalation, when I understood this song was something to behold.

“You’re not the guy that cheats, and you’re afraid that she might leave,” Germanotto observes. “If I get too close she might scream—how bad, bad do you want me.”

Germanatto keeps pushing forward into that space between camp or theatricality, an eroticism or sensuality, and a kind of fear, or unsettled sensation, in the song’s second verse. “You panic in your sleep, and you feel like such a creep,” she exclaims. “Cause with your eyes closed, you might peek—so hot, hot that you can’t speak.”

A good pop song, or a pop song that knows exactly what it’s doing, will structure itself around a gigantic, shout-along chorus. And “How Bad Do U Want Me” is already doing the work through this alluring and unnerving narrative, and it is putting in overtime with just how enormous, anthemic, and powerful of a chorus Germanatto has put together here. If there is an immediacy felt at other places in the song, here, it becomes much more emergent—a kind of seething, lusty desperation.

“Cause you like my hair, my ripped up jeans—you like the bad girl I got in me,” she bellows with intensity. “She’s on your mind like all the time, but I got a tattoo for us last week. Even good boys bleed,” she continues, before asking the titular question. “How bad do you want me?”

“You hate the crash, but you love the rush, and I’ll make your heart weak every time,” she adds, pushing the chorus out higher. “You hear my name, ‘cause she’s in your brain, but I’m here to kiss you in real life.”

And even in the song’s, at times, playful nature, there are these flashes of not menace, exactly, but of something dangerous, or truly frightening to give consideration to. The first is when, near the end of the chorus, she exclaims, “Bout to cause a scene—how bad do you want me.”

The second is, just a little later on, after undulating through these subtle changes, or small alterations, through phrases—“You love a good girl bad” and “you make a bad girl mad,” she refers to this pattern, or the larger narrative, as a “psychotic love theme.”

The last is the warning, or growled threat, that comes near the end. “That girl in your head ain’t real—how bad do you want me for real.”

Want leads to more want. And we are taken up to a point. A moment. Seemingly just before something is going to happen. There is no resolve, or moment after, in “How Bad Do U Want Me.” And we have to be okay, as listeners, with the wild ride the song takes us on, both musically, and the vibe it bases itself around, and this story—volatile and desperate, thrashing around for the attention it wants. Bold and blindingly bright, and unnerving, it is a huge declaration of both lust, or desire, and love, and what happens when all of those things blur together into something beautiful and terrifying.

*

Back to Friends by Sombr

There is a world where I probably never hear this song—and maybe, if I were even just slightly less chronically online, there’s probably a world where I am never aware of Shane Michael Boose, who has been releasing music under the name Sombr (though stylized in all lowercase) since 2021.

For as hesitant as I am to say it, my introduction to “Back to Friends,” and Boose, was one of those right place, right time moments. In the car, late at night—much later than I am often out in the world. Futzing with an embarrassingly temperamental stereo, I turned the radio on, and as a De La Soul track was coming to an end, the opening, flattened synthesizer notes to “Back to Friends” started to ripple through the speakers.

And there is a lot, musically, that happens, within the first few moments of the song—the song itself is rather surprising in just how unrelenting and efficient, or lean, it is, with Boose arriving at the first chorus less than 45 seconds into its three-minute-and-change running time. And I think, more than anything, “Back to Friends,” despite just how inherently toxic its lyrics are—a kind of “woe is me” masculinity that is nearly impossible for me to be tolerant of, and despite how polarizing or obnoxious of a figure, or persona, Boose might be, the thing about this song is that I can understand, and appreciate, how well assembled of a piece of pop music it is.

There is something extremely familiar—almost eerily familiar, honestly, about “Back to Friends,” especially as it is collecting itself, before Boose’s yelpy, blown-out vocals come in. And even then, it is a song that is so successful in how it is put together, it leaves you, at least the first time you hear it, wondering if it is something you’ve heard before.

From those brief, opening, kind of muted notes, to how those make way for a slinking, head-nodding rhythm, and the airy, echoing piano chords that are both, somehow, melancholic and triumphant at the same time, Boose knows what he is doing, in terms of borrowing aesthetics, or tones, from pop music’s past. If the instrumental introductory part of the song is reminiscent of a kind of loose, electro-adjacent sound from the very early 90s, once the layered, buildup of Boose’s wordless singing, and snarly guitar chord chugging arrives shortly thereafter, you can hear the influence of, or at least an interest in what I think is often referred to as “indie sleaze.”

There is an irony to this, I guess. But there both is, and is not, a lot that happens in “Back to Friends.” What I mean by that is it is ultimately a relatively simply structured song—it follows a verse/chorus/verse structure, and it moves at such a pace that it never does run the risk of overstaying its welcome, which is a good thing, because one of its glaring flaws is how it exhausts itself and its ideas upon reaching the bridge section, which simply does not work at all. The verses themselves are brief—the first verse is truly two lines; the second, just a little bit longer. And what its presented in the verses, lyrically, is evocative, yes, sure, in a kind of lusty, ambiguous, fragmented way, but it is truly used as a vehicle to move us quickly into the chorus. Because like any well-constructed pop song, that, regardless of how smart it is, or how sharp the songwriter is, “Back to Friends” hinges itself on a huge, memorable chorus.

“Touch my body tender,” Boose howls through distortion while a snarly electric guitar chugs underneath him, and the percussive elements of the song—a blend of both programming and live drums—create a nervy, slinking rhythm. “Cause the feeling makes me weak. Kicking off the covers—I see the ceiling while you’re looking down at me.”

“Back to Friends” reveals itself, rather quickly, as not a breakup song, but as one of a broken heart. Boose, as the protagonist, has been spurned by the object of his affection, who wishes to keep things much more casual than he would like—“It was last December,” he recalls in the second verse. “You were laying’ on my chest. I still remember—I was scared to take a breath…didn’t want to move your head.”

What he describes is fragile, yes, but what is even more fragile is Boose himself, which does make it, at times, hard to listen to the song, even in just how well put together and infectious the chorus is. “Back to Friends” is a song where both there is, and is not, a lot happening. It follows a pattern, and it does it with ease, and it knows just how much to lift itself during the chorus to make that stand out. There is really little, if any, deviation from the rhythm and chordal progressions—but there is, like, a lot happening with the layers, or at least, it feels like there is a lot happening in terms of how the elements are coming together, and coming together at just the right time. “How can we go back to being friends when we just shared a bed,” Boose sneers in the chorus, his voice magnified by a number of added, textural layers. “How can you look at me and pretend I’m someone you never met.”

I was dubious of Shane Michael Boose as “Back to Friends” was fading out on the radio, and the late-night DJ came on to talk about the songs that had just played—mentioning Boose was releasing his debut full-length under the name Sombr the following week. The title of the album is I Barely Know Her, which is of course, just kind of gross, and is an entendre punchline here for him, and the scorned lothario he perhaps sees himself as.

Boose was born the year I graduated from college. He is a young person, who is making music that is, regardless of if that was the intention, for an even younger audience. There is something about him, at least to me, that screams “industry plant.” Maybe it’s his looks—he’s a big mess of shaggy black hair and those cheekbones could cut someone. Maybe it’s because I had literally never heard of him and then he was suddenly everywhere. He gained an audience, originally, through TikTok, and what I understand is that there are corners of contemporary popular music that aren’t for me. I think Sombr is one of those corners. I don’t need to listen to anything else off of I Barely Know Her. I mean, I don’t think I wish to listen to anything else off of it. Again, there is a world where if I were not in the car, late at night, with the radio on, I would have never heard “Back to Friends.”

Whether or not Shane Michael Boose is an industry plant or just a handsome young man with some musical talent, who managed to use the Internet as a means of quickly finding success—I mean, I guess it doesn’t matter. This is a fascinating, hypnotic slice of pop music that somehow manages to find a space between being very of the moment, while borrowing just enough from the recent past to make you feel already at home when hearing it.

Be Kind by Annahstasia

And this, of course, may sound heavy-handed, but something that I think about—not often, but often enough- is silence. And what silence sounds like. If that makes sense. Like, what we, or at least, what I will hear, or notice, within what we consider to be a moment absent of sound.

Because there is, or there can be, a quiet. And this, of course, will continue to sound heavy-handed, maybe even more so, but in that quiet or what we perceive to be silence, I think about what we do notice—what forms or occur within that space, however large or small it might be.

I tell you all of that to tell you this—I think about the way silence is used within pop music. Or how it is used. The feeling or tension it creates, or how it hangs in midair, between notes, however far apart they may be.

I think about the way silence is, and can be, used as an instrument. You don’t play the silence. But, you play with it. You find the ways to weave it into the fabric of the song. I think about the kind of thoughtfulness, and the intelligence that is necessary to not only work with it, but to work with it in a way that creates the lasting, or resonant effect that you wish for it to have.

The first thing that you hear Annahstasia Enuke say on “Be Kind,” the absolutely jaw-dropping opening track to her debut full-length, Tether, is “There’s a pile of CDs in the corner over there.” And that line, alone, and the simple but suggestive imagery it holds, is of course quite vivid. But it is how she says it. The way she controls her voice, showing a kind of restraint within the first few seconds of the song that is undeniably impressive. The way she can hold a note—extending it out, at least in this instance, much further than you think it may need to go.

And the way she can play with silence. Or the idea of space. The way it hangs, midair, between two points, or notes. And then what forms within that distance.

“Be Kind” is not misleading as an opening track, w/r/t the tone that Enuke conjures, and then sustains, through its five minutes and change. But it is also not entirely representative of the rest of Tether. I say that, because not every song is like that. But every song is like that. She is a powerful, commanding, thoughtful singer and songwriter. Nearly every song on the record is impressive, and genuinely interesting to hear, and often showcases her dynamism as a songwriter. Not every song is this sparse and spectral.

Something that is impressive about Enuke, and Tether, and “Be Kind,” in particular, is how it walks this line where it could, and might, keep a listener at an arm’s length. It’s haunting. It’s intentional in its pacing. She plays with silence, and enormous spaces in between notes, or moments, like they are another instrument in the arrangement. I am remiss to say that it is “catchy,” because “Be Kind” is not that kind of song. That is not to say there are not moments on Tether that are infectiously written and structured through a convergence of folk and soul music. I would say “Be Kind” is memorable. It is hypnotic, especially its first half—because it does work in two movements, or pieces of a larger whole.

There is a growing, churning feeling to how Enuke controls the frenetic fluttering of the acoustic guitar strings. It swirls, not with malice, but with intensity, like a caldron being stirred. It creates a rhythm, slightly erratic in how it continues to tumble forward—at times with abandon, and other moments, with great caution, creating the foundation for Enuke’s resonant, otherworldly voice to float above it. She, too, using both abandon, and caution, in how she crafts an ambiguous, but extraordinarily vivid narrative.

“There’s a pile of CDs in the corner over there,” she begins, after holding the first two words and creating an intentional pause, or space, before literally diving headfirst into the rest of the line, before continuing. “Sharing the ground with a tree that’s the saving grace for the surrounding, poison air.”

Forgoing completely, at least in this first half, a more typical song structure, Enuke pushes forward into another verse without hesitation. “The longer I stare at this ghetto diamond,” she reflects, “I find rare, and different—this pile of memories that was always lying there.”

Even with how tense and erratic the momentum of her plucking the strings of the acoustic guitar sounds, as the song gathers itself, there is something hypnotic about it. Sensual even. The way it pulls you in. Enuke complements that with the use of repetition and creation of a more focused or clearer melody in the next verse. “I danced for three days,” she exclaims. “I danced for three days. I danced for three days in the arms of my lover that I met in the grown phase—who holds on through my growing pains.”

Often, in writing about music, there is something about me that feels like it is, perhaps, too much, or somewhat unnecessary, to include every lyric, when I am working through analysis, but the way that the first portion of “Be Kind” unfolds is truly like a poem—hyper literate, vivid, shadowy. So I think, as a means of understanding where Enuke wishes to take us, and how we get into the second half of the song, it behooves me to include the subsequent verses.

“I deserve to rest in a California king bed with my arms stretched out,” she confesses. “And my dreams bleeding from my head into the sheets instead.”

“Maybe I’m the chosen one—your lost and rambling son,” Enuke exclaims, in the final verse, before the shift in “Be Kind”’s direction. “I’ll leave you standing in a land that I deserted for a better hand.”

As “Be Kind” approaches its tonal, and directional shift, Enuke, again, plays with the notion of silence, using these enormous, somewhat dramatic, and extremely effective pauses, while her fingers gradually are lifted from the flicking of the guitar strings, and her voice just hangs, slowly uttering the phrase that signals the movement from this first part into the second.

“You see,” she begins. “I never learned to be kind.”

“But,” she continues. “I hear you get used to the pain of heartbreak, again and again.”

And it is here that “Be Kind” shifts into something much more tender. Not that the first two minutes of it are menacing, but there is a darkness, or something ominous, coursing through both the intensity with which Enuke delivers her vocals, and the way her fingers flutter on the strings of her guitar. The tempo, and pacing, of the song shift, and a softer rhythm reveals itself as she quietly strums the guitar, and delicate, somber notes from the piano punctuate, underscored by the low, slow accompaniment of string instruments.

And there is a juxtaposition that is created, then, in this tonal shift, because for as softened as “Be Kind” becomes, there is still an emergent intensity to Enuke’s lyricism—oscillating in a space that exists between a bright flash of hope, and the resignation of heartbreak.

“I won’t be heartless, so don’t be heartless with me,” she asks, playing with the words, and the repetition, creating an incantation of sorts. “I won’t be careless, so don’t be careless with me,” she pleads, then later, “I won’t be careless. So don’t make me care less.”

And there is a kind of exhaustive feeling that comes, then, in the closing moments of the song, while all the elements are swirling around her. “I won’t be kind,” she attests. “If you’ll be, I’ll be kind,” then slowly repeats, in a low, somber voice, giving in to the exhaustive resignation. “If you’ll be.”

Referring to “Be Kind” as stunning seems like an understatement. It is the kind of song that, even months after I first heard it, it still knocks the wind out of me completely when I listen—specifically, the haunting, sorrowful, graceful way it winds itself down. It is an utterly fascinating song—both slightly off-putting while still being, at least in the second half, rather warm, and inviting, depicting the way emotions can quickly shift and the feeling within a moment can change, and what the silences in-between carry.

Blood In The Vines by Sister.

And there are any number of songwriting techniques, or devices, that I find compelling, or genuinely interesting. And, really, the more I think about it, a number of them actually occur within the creeping, alluring opening track to Sister.’s sophomore album, Two Birds. But one that I often find to be amongst the most fascinating is when a specific expression, or phrase, is used in a song—appearing in the chorus, or as a chorus, I suppose—and when it is referenced again, or returned to later on, there is just the slight alteration made to it.

Because, within that change—and again, it is often a subtle one. Or at least intended to be so, if it is done well, and through the hands of capable and thoughtful songwriters. But this change, or alteration, hints at, or speaks volumes of, something much, much larger and more resonant—the kind of thing that the song wants you to give consideration to long after you’ve finished listening.

It’s something unspoken. And maybe it’s not understood, exactly. But something that is acknowledged regardless.

And there is an intersection, or a delicate balance, between something that feels like both too much, and not enough.

One thing about me is I genuinely adore a charming and wholesome origin story, or beginning of something—like a creative partnership. Founded as a friendship project between college roommates and best friends Ceci Sturman and Hannah Pruzinsky, Sister. has organically evolved into a trio, now including multi-instrumentalist James Chrisman. Though even with the involvement of additional personnel in the group, Pruzinsky and Sturman, who share both songwriting and vocal duties, continue to explore the dynamic they have as closely connected individuals within their writing.

And in that exploration, there is, of course, that balance. Or that intersection. How close is too close. Is it ever close enough.

As it unfolds with intention across nearly six minutes, another songwriting technique, or device, that I find genuinely interesting or compelling that occurs within “Blood in The Vines” is the way the group continues to find, with ease, the tonal shifts in the song as it propels itself forward. It seems a little out of place, or perhaps simply just not the right descriptor, to refer to the song as being “seductive,” but there is a kind of unsettling seduction that we experience as listeners.

The song itself, as it opens, and gathers itself, is a little playful in how it bounces along—there it isn’t jubilant by any means, but it slinks along in a way that does not only ask you to move your body in time with it, but actually demands you surrender yourself without question to the pulsating beckons of the rhythm—the shuffling percussive elements that never overpower, and the wet sounding reverberating plunks of the electric guitar strings.

This kind of bounce, or slight rollick, is leading to something much darker in tone—I am remiss to say “Blood in The Vines” is an ominous song, both in lyrics and in arranging, but a stark, and well-orchestrated shift occurs as we’re led into the chorus. Skittering on an edge of dissonance, the song doesn’t ascend or become explosive, but the restraint is loosened just enough, and in doing so, there is this raw, haunted unease that forms, with the electric guitar becoming much snarlier, and a sense of urgency growing within the rhythm. And more than anything, even in the unsettled nature, “Blood in The Vines” is hypnotic in the way the elements swirl together. Not in a dizzying way. A kind of dreamlike haze that is all too easy to lose yourself in, writhing in a kind of abandon.

There is a space that exists when something is both too much and not enough. It’s a frustrating place to find yourself. Or, it can be frustrating, or tumultuous, because it can be challenging—not all the time, to find the balance, and sustain it. Where the kind of closeness, or intertwined nature, you share, does work.

Something admirable about the way that Pruzinsky and Sturman write is the, and, again, a technique, or device, within songwriting that I find endlessly fascinating, is the way to reveal as much as you wish to, or divulge something personal, or insular, but to do so in such a literate, poetic way that it is obscured in an intentional ambiguity.

There is a sweetness, or a tenderness, that is depicted. Moments. Or these fragments that are working towards something larger and capable of becoming volatile. And the way it unfolds with meticulous precision, or what it depicts, and the kind of weight beneath it all, is something to truly behold.

“We share the water—I wash your hair,” Hannah Pruzinsky begins, quietly, in the opening verse. “When you’re impatient your skin burns red. You grabbed the wrong hand—we were just friends,” they continue, with the slightest shift in tone beginning in this moment. “I overthought it. I dropped your wrist.”

And there is still a tenderness, and a kind of affection, that is detailed the further into “Blood in The Vines” we are lured, but the lyrics do begin oscillating more and more into a kind of discomfort, or inevitable frustration, forming in the space when you are too close but not close enough.

When it is both too much but still not enough.

‘You look just like me,” Pruzinsky in the second verse. “That’s kind of sweet. Said we’d go dancing—save our bad day. We’re always fighting,” they reveal, almost as an aside. “And that’s okay.” The third verse, then, returns to this specific moment. “Mirror your movements, not like this,” they continue, before the kind of over-saturation quickly ripples to the surface. “Leave room for Jesus—can we just dance?,” they resign, exasperatedly.

There are any number of songwriting techniques or devices that I do find compelling, or genuinely interesting. And one of those is when a specific expression, or phrase, is used, and when it is referenced again, or returned to later on, there is just the slightest alteration made to it. Because, within that change—again, it is often very subtle. Or that is the intention. But this change, or this alteration—it hints at, or speaks volumes of, something much larger and more resonant.

“Blood in The Vines” manages to pull this off in two different instances—and the utterly transfixing nature of how the song is assembled doesn’t make it hard to notice, exactly, but these are ultimately the kind of small details that do reveal themselves over time. The first is in the way the word “suffocate” is used, and what the implications are in each occurrence. “Suffocating,” they sing, eerily, in the first chorus; then, changing it both the second and third time to “Suffocate it.” The shift, and implication is shadowy, yes. But it is vivid, regardless.

And I don’t know if I caught this, really, when sitting down with Two Birds prior to its release this summer, but there is this additional alteration, speaking to the larger conceit of “Blood in The Vines” that takes place as the titular phrase is uttered slowly, underscored by this primal, wordless cooing. The expression itself is delivered within a kind of rhythm that lures—a come-hither kind of motion into the darkness. “Blood in the vines,” then, when repeated later, is alternated with the slightest change to “Blood in the vibes,” and the execution of the shift and repetition is so subtle.

But it of course speaks volumes. And it is resonant in a way that haunts after the song drifts towards its ending. And there is no easy answer, or resolution, in “Blood in The Vines.” And I think that’s the point. Or one of the points it wishes to convey, doing so in a way that is honestly both very apparent, and not. Because there are these balances that are delicate to sustain. When we are perhaps too close, but it never feels close enough. When it’s too much but not enough. The tensions that rise, and the spaces we look for release. And what that tension is capable of creating. There is beauty in it. What the tension creates. How tightly intertwined we may find ourselves to another—and what can result from knowing someone so well and working with them so closely. Both completely unwilling to loosen the grip. It isn’t private, exactly. But it is of a personal nature. But what is so fascinating about how Pruzinsky and Sturman operate in how they write is not just what they are interested in revealing but how they wish to do so.

And yes, “Blood in The Vines” is an attention grabbing opening track—it’s nervy, volatile, and honestly infectious and mesmerizing in how it sounds. But the way it depicts creativity and friendship, doing so through these hyper-specific and incredibly literate fragments, is astonishing, using imagery that hangs in the air, like a specter.

Crybaby by SZA

We tell ourselves stories in order to live

I’m always thinking about that. The line that Joan Didion uses in the opening of her essay “The White Album,” and the stories that we do tell ourselves, in order to continue living.

Because there are the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves. And I am often thinking about the way we wish to be perceived. And then, in turn, there is how we are perceived. We might not think in these terms, exactly, but there is the way we see ourselves as the hero of the story—our story. The one we tell ourselves in order to live. And if not the hero, we at least, try not to depict ourselves as the antagonist in our own lives.

There are the ways, of course, that we are portrayed when someone else tells that same story. The story they tell themselves in order to live. Because the truth is we might not even be a character, in their lives at all. And if we, in order to live, see ourselves as a lovable albeit flawed protagonist, I am confident we are the villain to someone else.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

I know you told stories about me.

Most of them awful.

All of them true.

Within my own story, the one I tell myself, I do not see myself as lovable albeit flawed. I think, if anything, I see myself as the latter.

I stop short of saying that, in contemporary popular music, I am always looking for glimpses of myself in what I hear—but a song is, of course, more resonant, and is something that I will, for better or worse, carry with me, if it offers me a reflection—often one that is humbling, if not unflattering.

Something that, and I am not sure if a lot of other listeners, give this as much consideration, but something that I find is how much self-deprecation Solana Rowe writes into her lyrics. She can be full of confidence, yes, or bravado. She can be lusty. But there is also this doubt, or uncertainty. A frustration—with others certainly, but mostly with herself. She uses it intelligently, or sharply—peppering it in, sometimes as an aside, within the context of something larger. But there are moments when it all comes rising to the surface. “Crybaby” is like that. And for some, at least on paper, an entire song hinged on a self-effacing, “woe is me,” may not sound that genuinely interesting. A pity party that nobody wants an invitation to. But Rowe is smarter than that, as she continues to show time and time again.

It takes a little effort to describe Lana—billed as a deluxe edition to SZA’s 2022 full-length, SOS, Lana arrived two years later, to the day, and featured 15 additional songs. At least for me, it serves as a continuation—a collection of material that had been written and recorded for SOS, as well as newer songs written to be included here.

In writing about contemporary popular music, I often speak about the dynamism of an artist. Maybe, I talk about that too much. But it is something I notice. How an artist can continue to effortlessly and often gracefully shift in tone. Solana Rowe is, of course, a wildly dynamic artist. Operating, primarily, from an R&B and hip-hop center, she often, and with ease, transcends that with arrangements existing in a kind of pop adjacency, or even a comfortable, nostalgic warmth from a 1990s alternative rock-inspired edge.

“Crybaby,” sequenced within the final third of Lana, not only places itself, in terms of arranging, within Rowe’s more R&B-influenced tracks, but it smolders and dazzles with a kind of homage to a very specific era of swooning soul music.

Because of that homage, and this feeling, there is a kind of familiarity to “Crybaby,” as it begins, and collects itself. Familiar, and also very solemn, or mournful—opening with a thick, rumbling bass line, as the quivering tones of an electric piano shift, serving as an underscore for the bass, as well as the melancholic notes plucked out on the strings of an electric guitar. And musically, as a few more elements are introduced, including the crisp taps of the hi-hat cymbal and pinging of the snare drum, and some more flourishes on a higher pitched, funk adjacent keyboard, the song remains relatively steady, or at least Rowe never really allows it to get away from her, even as it swells as a means of punctuating her vocal performance in the chorus—it is a song that, in continuing to slow churn and shuffle away, creates a robust and complimentary atmosphere for Rowe to walk through her laments, and reflections, in real time.

“Maybe, if that attitude took a backseat, Miss Know-It All, you’d find a man,” Rowe begins, chastising herself, before adding a few lines later, “Maybe, if I stopped blaming the world for my faults, I could evolve. Maybe the pressure just made me too soft.”

Something that I am still finding a way to appreciate, and acknowledge, is that there is a difference between a song that asks for its lyrics to be dissected or analyzed, and a song that is, as a whole, working towards creating a vibe, where specific elements are not more important than others. “Crybaby,” then, seemingly walks a very thin line between those two—there is thought to Rowe’s lyricism. It is honest, and as she often is, unflinching in how she addresses herself.

The song’s structure, though, and its instrumentation, as it slowly lurches forward, effortlessly create a very specific and meticulous vibe, or atmosphere. And with that being said, I am remiss to say that the song’s verses are not, like, imperative to the larger ideas Rowe is presenting. However, they also feel a little like vessels to get from one point of the song, to another—one that is much more compelling and better developed, or articulate.

Because the tempo, and the arrangement, of “Crybaby” never really deviate, there is no real indication as the song shifts from verse, to the sprawling chorus. I would contend, though, that Rowe feels more comfortable within this portion, as the momentum does build, just slightly, as she finds the ways to play with the cadence and delivery of her words within the rhythm of the song. “All I seem to do is get in my way then blame you,” she explains, her words falling with a pointed kind of intention. “It’s just a cycle. Rinse. Recycle. You’re so sick—I’m so sick of me too.”

And it’s funny. And. I mean. Maybe that’s the point of a song like “Crybaby.” Because within what Rowe depicts, and what she is lamenting, she ultimately is unwilling to assume the responsibility—“Call me Miss Crybaby,” she howls. “It’s not my fault. It’s Murphy’s Law. What can go wrong will go wrong.”

“Crybaby,” in its warmth, and soulfulness, and the vibe that it conjures and sustains, is of course memorable as a whole. It is, though, specific moments—phrase turns, and the very real, visceral sentiments that come with them, that at least for me, make it a song that you are, like, not always in the right frame of mind to hear, but a song that is ultimately unforgettable.

There is a kind of exhausted, desperation that comes through in the pointed way Rowe concedes, “You’re so sick—I’m so sick of me too.” And she returns to that, when she resigns herself in the song’s final moments. “I know you told stories about me,” she explains. “Most of them awful—all of them true.”

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

I’m always thinking about that. The way Joan Didion opens up “The White Album.” And the way we do tell ourselves stories, in an effort to continue living. The stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves. How we wish to be perceived. How others perceive us. The negative space that forms in the middle when those things no longer connect.

We become the antagonist in our own lives. In our own stories. It’s an uncomfortable and humbling, and sometimes humiliating place to find ourselves. Even as unflattering of a reflection as we are asked to gaze into through a song like “Crybaby,” there is a comfort in knowing that this kind of difficult realization is a shared experience.

You told stories about me. Most of them awful.

All of them true.

Largo by Vega Trails

And, I mean, over time, your tastes, or your interests, change. Or grow. Because there was a time, a little over a decade ago, when I listened to a lot more—and in many cases, actively sought out, often experimental in nature ambient and instrumental music. And I am remiss to say that it is a style of music that I “outgrew,” but what I did find, is that it has become something I was much less interested in, or was not as compelled by as I once had been.

Regardless, even if I were to still actively listen to ambient, instrumental music, or were seeking out new performers and recent releases, I do not believe that these are the kinds of things that I could easily write about thoughtfully or analytically.

And maybe it never was really that easy, in the earliest years of when I had first started writing about music, and beginning to think more critically about it. But the stakes, of what ended up on the page, and the work that went into putting it all there, were all admittedly much lower then.

In writing about music, and in thinking about music analytically, and personally, I spend a lot of time giving consideration to a song’s lyrics, or what kind of writer the artist in question is—how those words are delivered within the song, yes, but what they could mean, or how we could take them of ourselves into the world that exists outside of the song.

I tell you all of that to tell you this—I spend a lot of time writing about things within contemporary popular music that are “evocative.” It’s a word I am aware that, for well over six years, I have used more than I should. And in writing about something that is entirely instrumental, as a means of description, going into detail about the feeling, the mood that the song creates—what it evokes—is by no means all you have to work with, but a lot is hinging on the kind of experience or atmosphere that is conjured.

I hesitate to describe the project Vega Trails as experimental in its nature, because depending on how experimental something is, it can keep a listener at an arm’s length. If anything, I would say Vega Trails is rather daring in how it ultimately is the result of what occurs in the center of a convergence between music that is ambient in nature and sensibility, and contemporary or modern jazz. Originally founded as a duo with double-bassist Milo Fitzpatrick and saxophonist Jordan Smart, the project has expanded since its 2022 debut, Tremors In The Static, to now include much more additional and often lush instrumentation in the form of sweeping swing arraignments, bursts of percussion, piano and vibraphone, all of which play roles in the stunning opening track, “Largo,” from the group’s second full-length, Sierra Tracks.

In the short press release for Sierra Tracks, the word “cinematic” is used twice—once to describe the project, or group, itself, and again when talking about the feeling of the album from beginning to end. “Largo,” as it unfolds over five minutes and change does become rather cinematic, yes, but it also, and more importantly, understands how to build to that point with a very intentional pacing, and through the subtle use of tension—which, when released, does create a moment that is just simply remarkable in what it feels like washing over you.

Opening with an extended prelude of dissonance created by the eerie and icy scrapes from one of the string instruments, there is a brief pause before the deep rumbling and organic slapping of Fitzpatrick’s double bass slowly wander in, eventually forming a melody that, shortly thereafter, Smart’s saxophone begins to weave itself in and out of. It isn’t playful, exactly, because there is a kind of quiet, downcast, or somber nature to “Largo,” even as it begins to collect itself like this, but there is this fascinating interplay at work, with the two instruments finding the places, and moments, where they can lock into one another, and where they meticulously circle around each other.

The saxophone and the double bass connect into more of a focused melody, or groove, and are joined by a percussive element, then, while the chilly, glistening sounds of the string accompaniment slowly, and quietly gather themselves and glide in underneath before the low, resonant sweeps of the cello work themselves up to the front, followed by the rest of the string instruments, working effortlessly to create something that is truly majestic to not only hear, but also to feel.

I am remiss to say there is something unassuming about how “Largo” assembles itself—the quiet way it begins, and the pacing that it strikes while working towards the song’s big moment. Because it is all very intentional—the way that the cello’s lower, moody strings and the soaring, widescreen aesthetic of the string section, as a whole, and the melody they follow in this moment are deliberately placed where they are within the song’s structure. A smaller reveal leading us to a much larger one that sends “Largo” into a place of absolute, stunning ascendence.

With roughly two minutes left in the piece (I have always struggled with, when talking about instrumental or unconventional tracks if I am able to refer to them as “songs” or if they are more compositions or pieces) Fitzpatrick—presumably the group’s bandleader, guides all of the elements into one final hushed moment before letting go of the tension that he, and the other performers on the track, have worked to build. The strings do not necessarily swell in the second before this, but they begin to churn dramatically, and with just the briefest pause, or breath, in between, “Largo” lets go of itself, and soars to unimaginable heights, lead by the howling ascendence of Smart’s saxophone and the use of an overlapping echo that trails the notes, followed closely by the grand, swooning, lush string accompaniment, coming in underneath, with the track’s percussive elements loosening up—maintaining the rhythm, but opening itself up and creating just a little more space for the other elements to swirl around with a dazzling, and honestly stunning kind of beauty that is truly surprising and moving—becoming only more so with subsequent listens.

And for as often as I do analyze, and write about lyrics, and how there is a place in contemporary pop music for songs that are inherently much more lyric-based, or focused, there is also a space for something like this—something that is completely reliant on the vibe, or the feeling, that it creates, and then sustains. And I would contend that there is a musical language spoken here, within the feeling that the song evokes, through this final, enormous swell, and into where it recedes at its conclusion.

Yeah, “Largo” is cinematic. I don’t think calling it that, or referring to Vega Trails’ canonical works as a whole as cinematic, is a disservice, but I think that it doesn’t accurately articulate the kind of breathtaking power found on this track, specifically. The kind of arresting beauty that is created with meticulous thought and attention—the transformative and transcendental power it has to turn even the most banal or insignificant moments of the day into something much larger and more evocative than you had thought imaginable.

Love Me Alive by The Knocks and Dragonette

Pop music desires a body. This much has been said. I have said it, yes. Because it is something I have continued to think about throughout this calendar year. Thinking about all that it means. Or could mean. Because it, of course, can be understood or meant, any number of ways.

There is a want, though. In a pop song. There is something that propels the song’s protagonist forward, and the ride that we are taken along for. That something is often a “someone.” And part of that propulsion comes in the form of the chase. The frenetic dash towards that someone. The object of your affection. A running towards them for the very first time. Or, perhaps, it is a running after them. And they are just out of your grasp.

Pop music desires a body. And there is, of course, a want. And both that want, and the idea of a body, are present in the dazzling “Love Me Alive,” though it, lyrically, as this narrative does unfold, provides to us an anecdotally unique and reflective variation on the notion of desire, and want.

Their collaborative full-length, Revelation, is not the first time the electronic production duo James Patterson and Ben Ruttner have worked with vocalist Martina Sorbara—the three of them had collaborated in 2019, on the track “Slow Song,” and long before that, Ruttner and Patterson, as The Knocks, had provided tour support to the group Sorbara fronted at the time, Dragonette—the name she still performs under now as a solo endeavor.

The album, when taken as a whole, is intended to exist within a larger, more immersive and higher concept world including 1980s-inspired visuals—which, while admirable in how they complement the shimmering textures and homage to very era-specific pop music, they are not entirely necessary to enjoying songs from it on their own, out of this more insular context.

“Love Me Alive” is not a breakup song, exactly—or maybe it isn’t a breakup song in the way you think of one, when you hear that description. Set against a slick, glistening, post-disco aesthetic with what is quite a rather relentless nature to how its pacing and rhythm are structured, the song becomes an anthem of sorts—one that is held back slightly by restraint, as Sorbara, as the protagonist, explores the exhalation of relief that comes in a moment of freedom, while still wishing to run towards something, or rather, someone else.

Opening quietly with an oscillating twinkle of wonky, synthesizer tones, Ruttner and Patterson waste no time in crafting a thick, briskly plunked out bass line, that falls right into place against the snappy and crisp percussion, really finding the groove immediately, and is then joined by slinky plucks of the electric guitar that ascend, and are used as a means of punctuating Sobara’s lyrical delivery within the first verse.